1Polarization States and Jones Vectors¶

We have seen in that light is an electromagnetic wave which satisfies Maxwell’s equations and the wave equation derived therefrom. Since the electric field is a vector which oscillates as function of time in a certain direction, we say that the wave has a certain polarization. In this chapter we look at the different types of polarization and how the polarization of a light beam can be manipulated.

From Maxwell’s equations and the wave equation, we know that the (real) electric field of a time-harmonic plane wave is always perpendicular to the direction of propagation, which is the direction of the wave vector as well as the direction of the Poynting vector (the direction of the power flow). Let the wave propagate in the -direction:

Then the electric field vector does not have a -component and hence the real electric field at and at time can be written as

where and are positive amplitudes and , are the phases of the electric field components. While and are fixed, we can vary , , and . This degree of freedom is why different states of polarization exist: the state of polarization is determined by the ratio of the amplitudes and by the phase difference between the two orthogonal components of the light wave Fowles, 1989. Consider the electric field in a fixed plane :

The complex vector

is called the Jones vector. It is used to characterize the polarization state. Let us see how, at a fixed position in space, the electric field vector behaves as a function of time for different choices of , and .

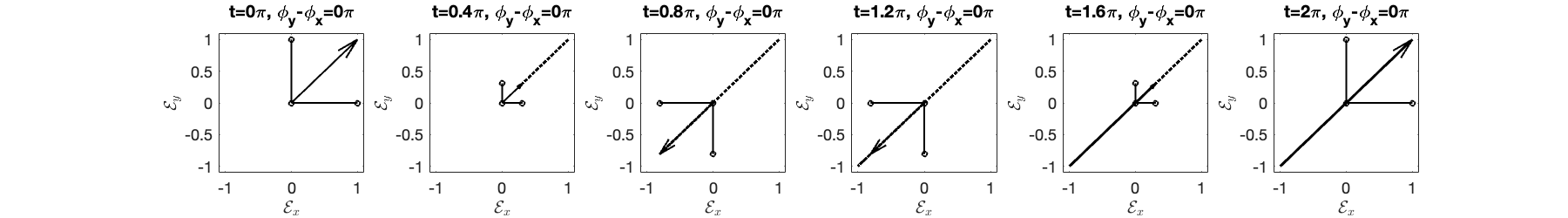

a) Linear polarization: or .] When we have

Equality of the phases: , means that the field components and are in phase: when is large, is large, and when is small, is small. We can write

which shows that for the electric field simply oscillates in one direction given by real the vector . See Figure 1.

If we have

In this case and are out of phase and the electric field oscillates in the direction given by the real vector .

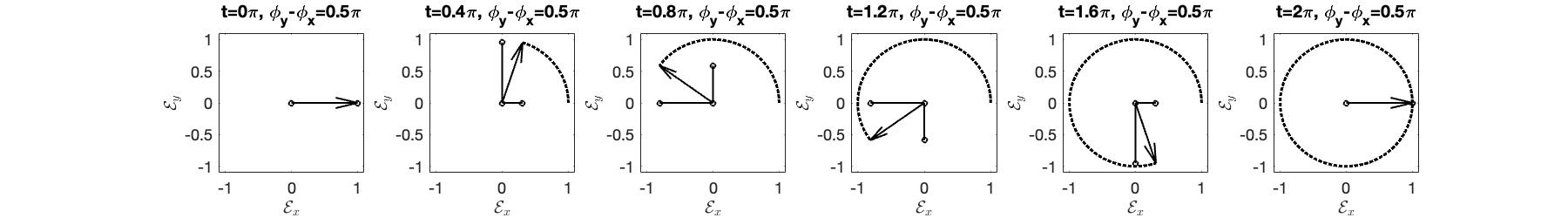

**b) Circular polarization: ** , . In this case the Jones vector is:

The field components and are radian (90 degrees) out of phase: when is large, is small, and when is small, is large. We can write for and with :

At a given position, the electric field vector moves along a circle as time proceeds. When for an observer looking towards the source, the electric field is rotating anti-clockwise, the polarization is called **left-circularly polarized ** (+ sign in Eq. (9)), while if the electric vector moves clockwise, the polarization is called **right-circularly polarized ** (- sign in Eq. (9)).

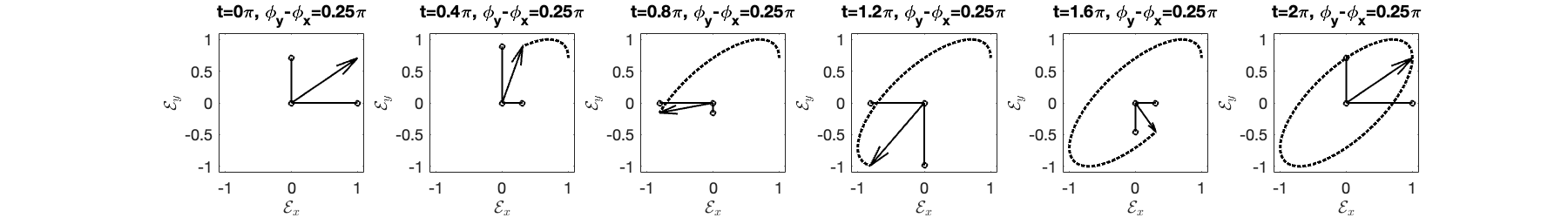

c) Elliptical polarization: , and arbitrary. The Jones vector is:

In this case we get instead of Eq. (9) (again taking ):

which shows that the electric vector moves along an ellipse with major and minor axes parallel to the - and -axis. When the + sign applies, the field is called left-elliptically polarized, otherwise it is called right-elliptically polarized.

d) Elliptical polarization: anything else, and arbitrary. The Jones vector is now the most general one:

It can be shown that the electric field vector moves always along an ellipse. The exact shape and orientation of this ellipse varies with the difference in phase and the ratio of the amplitude and, except when , the major and minor axis of the ellipse are not parallel to the - and -axis. See Figure 3.

Remarks.

Frequently the Jones vector is normalized such that

The normalized vector represents of course the same polarization state as the unnormalized one. In general, multiplying the Jones vector by a complex number does not change the polarization state. If we multiply for example by , this has the same result as changing the instant that , hence it does not change the polarization state. In fact:

We will show in the Angular Spectrum Method section of the Diffraction chapter that a general time-harmonic electromagnetic field, is a superposition of plane waves with wave vectors of the same length determined by the frequency of the wave but with different directions. An example is the electromagnetic field near the focal plane of a strongly converging lens. There is then no particular direction of propagation to which the electric field should be perpendicular. In other words, there is no obvious choice for a plane in which the electric field oscillates as function of time. It can nevertheless be shown that for every point in space such a plane exists, but the orientation of the plane varies in general with positionBorn & Wolf, 1999. In this chapter we only consider the field and polarization state of a single plane wave. Furthermore, the electric field in a certain point moves along an ellipse in the corresponding plane, but the shape of the ellipse and the orientation of its major axis can be arbitrary. We can conclude that in any point of an arbitrary time-harmonic electromagnetic field, the electric (and in fact also the magnetic) field vector prescribes as function of time an ellipse in some plane which depends on positionBorn & Wolf, 1999. In this chapter we only consider the field and polarization state of a single plane wave.

Figure 1:Linear polarization state of electromagnetic waves. The electric field vector oscillates along a single fixed direction perpendicular to the direction of propagation, tracing out a straight line in the plane perpendicular to the wave vector.

Figure 2:Circular polarization

Figure 3:Elliptical polarization

Illustration of different types of polarization. The horizontal and vertical arrows indicate the momentary field components . The thick arrow indicates the vector . The black curve indicates the trajectory of .

2Creating and Manipulating Polarization States¶

We have seen how Maxwell’s equations allow the existence of plane waves with many different states of polarization. But how can we create these states, and how do these states manifest themselves?

Natural light often does not have a definite polarization. Instead, the polarization fluctuates rapidly with time. To turn such randomly polarized light into linearly polarized light in a certain direction, we must extinguish the light polarized in the perpendicular direction.The remaining light is then linearly polarized along the desired direction. One could do this by using light reflected under the Brewster angle (which extinguishes p-polarized light), or one could let light pass through a dichroic crystal, which is a material which absorbs light polarized perpendicular to its so-called optic axis. A third method is sending the light through a wire grid polarizer, which consists of a metallic grating with sub-wavelength slits. Such a grating only transmits the electric field component that is perpendicular to the slits.

So suppose that with one of these methods we have obtained linearly polarized light. Then the question rises how the state of linear polarization can be changed into circularly or elliptically polarized light? Or how the state of linear polarization can be rotated over a certain angle? We have seen that the polarization state depends on the ratio of the amplitudes and on the phase difference of the orthogonal components and of the electric field. Thus, to change linearly polarized light to some other state of polarization, a certain phase shift (say ) must be introduced to one component (say ), and another phase shift to the orthogonal component . We can achieve this with a birefringent crystal, such as calcite. What is special about such a crystal is that it has two refractive indices: light polarized in a certain direction experiences a refractive index , while light polarized perpendicular to it feels another refractive index (the subscripts and stand for “ordinary” and “extraordinary”, but for our purpose we do not need to understand this terminology). The direction for which the refractive index is smallest (which can be either or ) is called the fast axis because its phase velocity is largest, and the other direction is the slow axis. Because there are two different refractive indices, one can see double images through a birefringent crystalHorvath et al., 2011. The difference between the two refractive indices is called the birefringence.

Suppose and that the fast axis, which corresponds to is aligned with , while the slow axis (which then has refractive index ) is aligned with . If the wave travels a distance through the crystal, will accumulate a phase , and will accumulate a phase . Thus, after propagation through the crystal the phase difference has increased by

2.1Jones Matrices¶

By letting light pass through crystals of different thicknesses we can create different phase differences between the orthogonal field components and in this way we can create different states of polarization. To be specific, let , as given by Eq. (4), be the Jones vector of the plane wave before the crystal. Then we have, for the Jones vector after the passage through the crystal:

where

A matrix such as , which transfers one state of polarization of a plane wave in another, is called a Jones matrix. Depending on the phase difference which a wave accumulates by traveling through the crystal, these devices are called quarter-wave plates (phase difference ), half-wave plates (phase difference ), or full-wave plates (phase difference ). The applications of these wave plates will be discussed in later sections.

Consider as example the Jones matrix which described the change of linear polarized light into circular polarization. Assume that we have diagonally (linearly) polarized light, so that

We want to change it to circularly polarized light, for which

where one can check that indeed . This can be done by passing the light through a crystal such that accumulates a phase difference of with respect to . The transformation by which this is accomplished can be written as

The matrix on the left is the Jones matrix describing the operation of a quarter-wave plate.

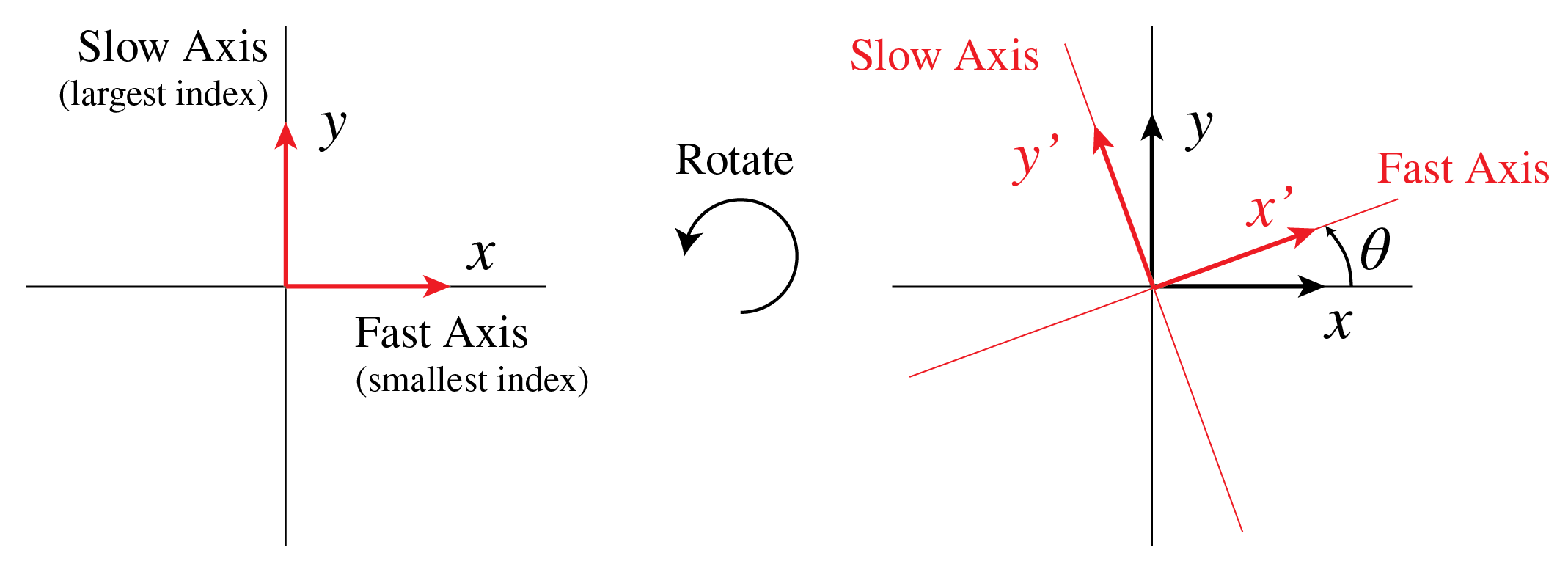

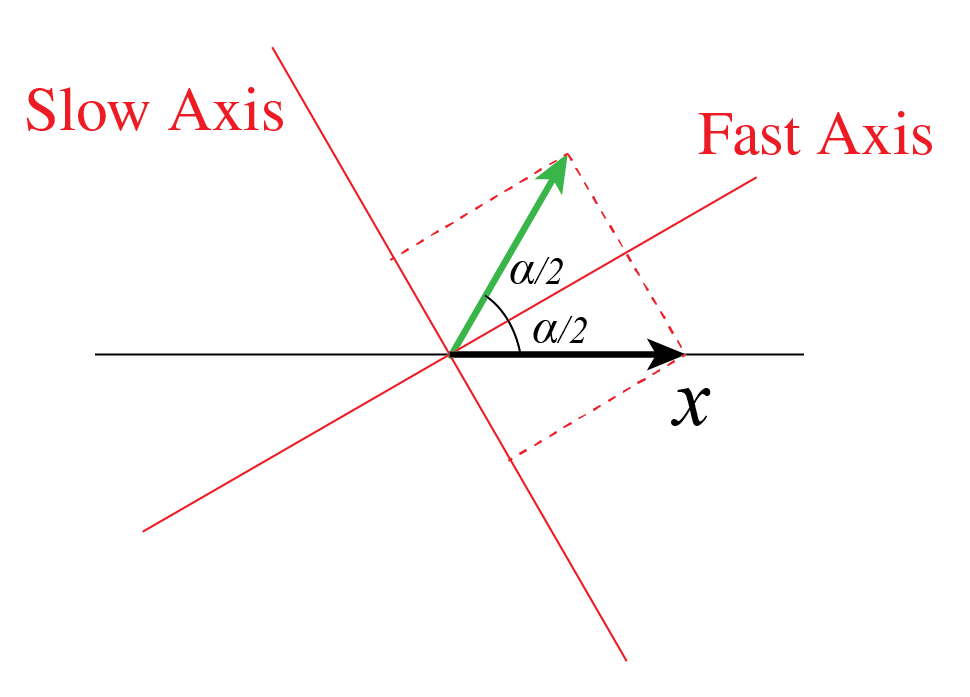

Another important Jones matrix is the rotation matrix. In the preceding discussion it was assumed that the fast and slow axes were aligned with the - and -direction (i.e. they were parallel to and ). Suppose now that the slow and fast axes of the wave plate no longer coincide with and , but rather with some other and as in Figure 4. In that case we apply a basis transformation: the electric field vector which is expressed in the , basis should first be expressed in the , basis before applying the Jones matrix of the wave plate to it. After applying the Jones matrix, the electric field has to be transformed back from the , basis to the , basis.

Let be given in terms of its components on the , basis:

To find the components , on the , basis:

we first write the unit vectors and in terms of the basis , (see Figure 4)

By substituting Eq. (23) and Eq. (24) into Eq. (22) we find

Comparing with Eq. (21) implies

where is the rotation matrix over an angle in the anti-clockwise direction: Hecht, 2002.

That indeed is a rotation over angle in the anti-clockwise direction is easy to see by considering what happens when is applied to the vector Hecht, 2002.

This relationship expresses the components , of the Jones vector on the , basis, which is aligned with the fast and slow axes of the crystal, in terms of the components and on the original basis , . If the matrix describes the Jones matrix as defined in Eq. (17), then the matrix for the same wave plate but with as slow and as fast axis, is, with respect to the , basis, given by:

This is a standard result from linear algebra involving basis transformations.

Figure 4:If the wave plate is rotated, the fast and slow axis no longer correspond to and . Instead, we have to introduce a new coordinate system ().

2.2Linear polarizers¶

A polarizer that only transmits horizontally polarized light is described by the Jones matrix:

Clearly, horizontally polarized light is completely transmitted, while vertically polarized light is not transmitted at all. More generally, for light that is polarized at an angle , we get

The amplitude of the transmitted field is reduced by the factor , which implies that the intensity of the transmitted light is reduced by the factor . This relation is known as Malus’ law.

2.3Degree of Polarization¶

Natural light such as sun light is unpolarized. The instantaneous polarization of unpolarized light fluctuates rapidly in a random manner. A linear polarizer produces linear polarized light from unpolarized light. It follows from Eq. (29) that the intensity transmitted by a linear polarizer when unpolarized light is incident, is the average value of namely , times the incident intensity.

Light that is a mixture of polarized and unpolarized light is called partially polarized. The degree of polarization is defined as the fraction of the total intensity that is polarized:

2.4Quarter-Wave Plates¶

A quarter-wave plate has already been introduced above. It introduces a phase shift of , so its Jones matrix is

because . To describe the actual transmission through the quarter-wave plate, the matrix should be multiplied by some global phase factor, but because we only care about the phase difference between the field components, this global phase factor can be omitted without problem. The quarter-wave plate is typically used to convert linearly polarized light to elliptically polarized light and vice-versaSaleh & Teich, 2007. If the incident light is linearly polarized at angle , the state of polarization after the quarter-wave plate is

In particular, if incident light is linear polarized under , or equivalently, if the quarter wave plate is rotated over this angle, it will transform linearly polarized light into circularly polarized light (and vice versa).

A demonstration is shown inBartholinus, 1669.

2.5Half-Wave Plates¶

A half-wave plate introduces a phase shift of , so its Jones matrix is

because . An important application of the half-wave plate is to change the orientation of linearly polarized lightFowles, 1989. After all, what this matrix does is mirroring the polarization state in the -axis. Thus, if we choose our mirroring axis correctly (i.e. if we choose the orientation of the wave plate correctly), we can change the direction in which the light is linearly polarized arbitrarilyGoldstein, 2011. To give an example: a wave with linear polarization parallel to the -direction, can be rotated over angle by rotating the crystal such that the fast axis makes angle with the -axis. Upon propagation through the crystal, the slow axis gets an additional phase of , due to which the electric vector makes angle with the -axis (see Figure 4). It is not difficult to verify that when the fast and slow axis are interchanged, the same linear state of polarization results.

Figure 4:Rotation of horizontally polarized light over an angle using a half-wave plate.

2.6Full-Wave Plates¶

A full-wave plate introduces a phase difference of , which is the same as introducing no phase difference between the two field components. So what can possibly be an application for a full-wave plate? We recall from Eq. (15) that the phase difference is only for a particular wavelength. If we send through linearly (say vertically) polarized light of other wavelengths, these will become elliptically polarized, while the light with the correct wavelength will stay vertically polarized. If we then let all the light pass through a horizontal polarizer, the light with wavelength will be completely extinguished, while the light of other wavelengths will be able to pass through at least partially. Therefore, * full-wave plates can be used to filter out specific wavelengths of light*.

3More on Jones matrices¶

If the direction of either the slow or fast axis is given and the ordinary and extra-ordinary refractive indices and , it is easy to write down the Jones matrix of a birefringent plate of given thickness using the rotation matrices, see Eq. (27). Instead of using the rotation matrices, one can also write down a system of equations for the elements of the Jones matrix. Suppose that and , are in the direction of the ordinary and the extra-ordinary axes, respectively. Then if the Jones matrix is

then

which implies

Similarly, for a linear polarizer it is simple to write down the Jones matrix if one knows the direction in which the polarizer absorbs or transmits all the light: use Eq. (28) in combination with the rotation matrices. Alternatively, if is in the direction of the linear polarizer and is perpendicular to it, we have

which is a system of equation of type Eq. (37) for the elements of the Jones matrix.

Suppose now that the complex (2,2)-matrix Eq. (35) is given. How can one verify whether this matrix corresponds to a linear polarizer or to a wave plate? Note that the elements of a Jones matrix are in general complex.

1. Linear polarizer. The matrix corresponds to a linear polarizer if there is a real vector which remains invariant under and all vectors orthogonal to this vector are mapped to zero. In other words, there must be an orthogonal basis of real eigenvectors and one of the eigenvalues must be 1 and the other 0. Hence, to check that a given matrix corresponds to a linear polarizer, one should verify that one eigenvalue is 1 and the other is 0 and furthermore that the eigenvectors are real orthogonal vectors. It is important to check that the eigenvectors are real because if they are not, they do not correspond to particular linear polarization directions and then the matrix does not correspond to a linear polarizer.

2. Wave plate. To show that the matrix corresponds to a wave plate, there should exist two real orthogonal eigenvectors with, in general, complex eigenvalues of modulus 1. In fact, one of the eigenvectors corresponds to the ordinary axis with refractive index , and the other to the extra-ordinary axis with refractive index . The eigenvalues are then

where is the thickness of the plate and is the wave number. Hence to verify that a -matrix corresponds to a wave plate, one has to compute the eigenvalues and check that these have modulus 1 and that the corresponding eigenvectors are real vectors and orthogonal.

3. Jones matrix for propagation through sugars In sugars, left and right circular-polarized light propagate with their own refractive index. Therefore sugars are called circular birefringent. The matrix Eq. (35) corresponds to propagation through sugar when there are two real orthogonal unit vectors and such that the circular polarization states

are eigenstates of with complex eigenvalues with modulus 1.

4Decomposition of an Elliptical polarization state into sums of Linear & of Circular States¶

Any elliptical polarization state can be written as the sum of two perpendicular linear polarized states:

Furthermore, any elliptical polarization state can be written as the sum of two circular polarization states, one right- and the other left-circular polarized:

We conclude that to study what happens to elliptic polarization, it suffices to consider two orthogonal linear polarizations, or, if that is more convenient, left- and right-circular polarized light. In a birefringent material each of two linear polarizations, namely parallel to the o-axis and parallel to the e-axis, propagate with their own refractive index. To predict what happens to an arbitrary linear polarization state which is not aligned to either of these axes, or more generally what happens to an elliptical polarization state, we write this polarization state as a linear combination of o- and e-states, i.e. we expand the field on the o- and e-basis.

To see what happens to an arbitrary elliptical polarization state in a circular birefringent material, the incident light is best written as linear combination of left-and right-circular polarizations.

5Chapter Summary¶

Polarization describes the orientation of the electric field vector oscillation in an electromagnetic wave.

Linear polarization: The electric field oscillates in a fixed direction; described by Jones vector with real components.

Circular polarization: The electric field rotates at constant amplitude; left-circular and right-circular have opposite handedness.

Elliptical polarization: The most general state; the electric field traces an ellipse, characterized by the ellipticity angle.

Jones vectors represent polarization states as 2D complex vectors; Jones matrices describe how optical elements transform polarization.

Polarizers transmit one polarization and block the orthogonal one; Malus’s Law gives transmitted intensity as .

Birefringence occurs when a material has different refractive indices for different polarization directions.

Wave plates: Quarter-wave plates convert linear to circular polarization (and vice versa); half-wave plates rotate linear polarization.

Optical activity rotates the plane of polarization as light propagates through certain materials.

Stokes parameters provide a complete description of partially polarized light, including unpolarized components.

6References¶

- Fowles, G. R. (1989). Introduction to Modern Optics. Dover Publications.

- Born, M., & Wolf, E. (1999). Principles of Optics (7th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Horvath, G., Barta, A., Pomozi, I., Suhai, B., Hegedus, R., Åkesson, S., Meyer-Rochow, B., & Wehner, R. (2011). Viking navigation using polarized skylight. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 467(2127), 651–660.

- Hecht, E. (2002). Optics (4th ed.). Addison Wesley.

- Saleh, B. E. A., & Teich, M. C. (2007). Fundamentals of Photonics (2nd ed.). Wiley-Interscience.

- Bartholinus, E. (1669). Experimenta crystalli islandici disdiaclastici quibus mira & insolita refractio detegitur. Copenhagen: Daniel Paulli.

- Fowles, G. R. (1989). Introduction to Modern Optics. Dover Publications.

- Goldstein, D. H. (2011). Polarized Light (3rd ed.). CRC Press.