Nice software for practicing geometrical optics:

https://

1Introduction¶

Geometrical optics is an old subject, but it is still essential to understand and design optical instruments such as camera’s, microscopes, telescopes etc. Geometrical optics started long before light was described as a wave as is done in wave optics, and long before it was discovered that light is an electromagnetic wave and that optics is part of electromagnetism.

In this chapter, we go back in history and treat geometrical optics. That may seem strange now that we have a much more accurate and better theory at our disposal. However, the predictions of geometrical optics are under quite common circumstances very useful and also very accurate. In fact, for many optical systems and practical instruments there is no alternative for geometrical optics because more accurate theories are much too complicated to use.

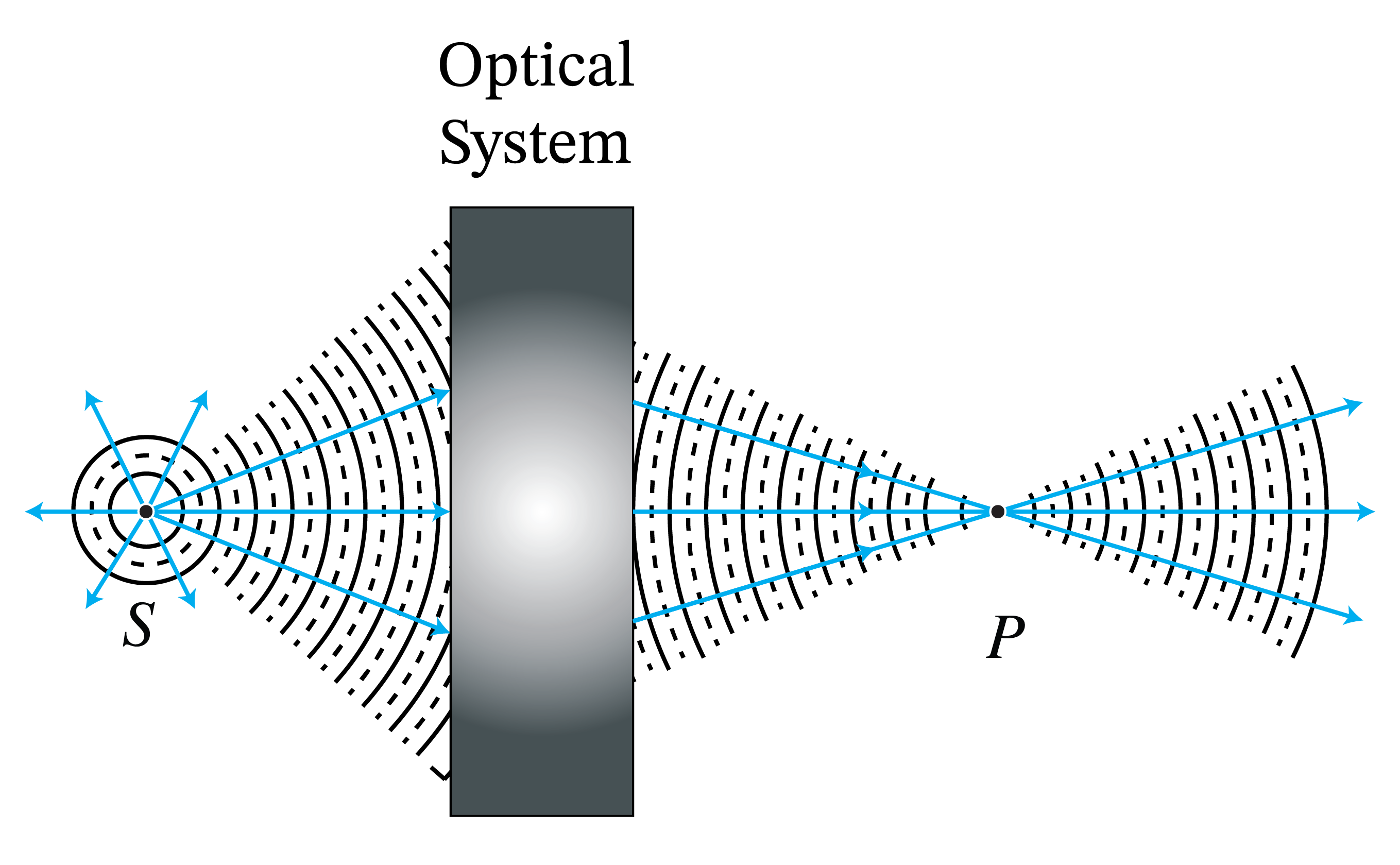

When a material is illuminated, its molecules start to radiate spherical waves (more precisely, they radiate like tiny electric dipoles) and the total wave scattered by the material is the sum of all these spherical waves. A time-harmonic wave has at every point in space and at every instant of time a well defined phase. A wave front is a set of space-time points where the phase has the same value. At any fixed time, the wave front is called a surface of constant phase. This surface moves with the phase velocity in the direction of its local normal.

For plane waves, we have shown in the previous chapter that the surfaces of constant phase are planes and that the normal to these surfaces is in the direction of the wave vector which coincides with the direction of the phase velocity as well as with the direction of the flow of energy (the direction of the Poynting vector). For general waves, the local direction of energy flow is given by the direction of the Poynting vector. Provided that the radius of curvature of the surfaces is much larger than the wavelength, the normal to the surfaces of constant phase may still be considered to be in the direction of the local flow of energy. Such waves behave locally as plane waves and their effect can be accurately described by the methods of geometrical optics.

Geometrical optics is based on the intuitive idea that light consists of a bundle of rays. But what is a ray?

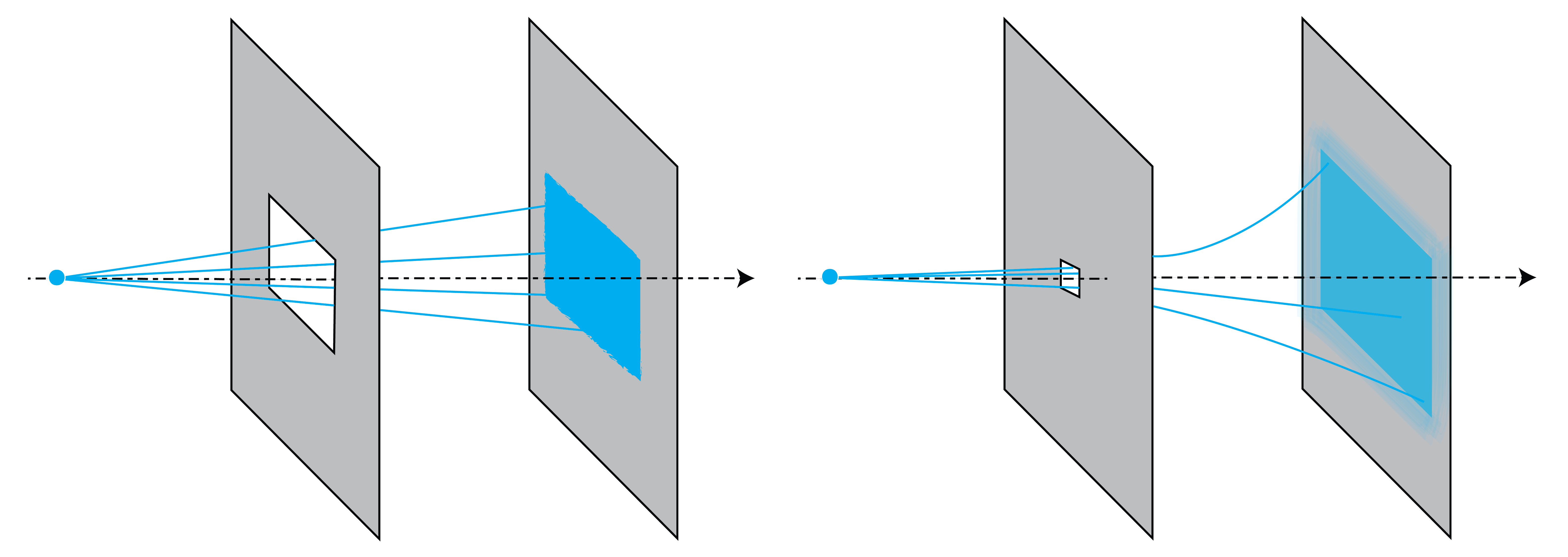

Consider a point source at some distance before an opaque screen with an aperture. According to the ray picture, the light distribution on a second screen further away from the source and parallel to the first screen is simply an enlarged copy of the aperture (see Figure 1). The copy is enlarged due to the fanning out of the rays. However, this description is only accurate when the wavelength of the light is very small compared to the diameter of the aperture. If the aperture is only ten times the wavelength, the pattern is much broader due to the bending of the rays around the edge of the aperture. This phenomenon is called diffraction. Diffraction can not be explained by geometrical optics and will be studied in .

Figure 1:Light distribution on a screen due to a rectangular aperture. Left: for a large aperture, we get an enlarged copy of the aperture. Right: for an aperture that is of the order of the wavelength there is strong bending (diffraction) of the light.

Geometrical optics is accurate when the sizes of the objects in the system are large compared to the wavelength. It is possible to derive geometrical optics from Maxwell’s equations by formally expanding the electromagnetic field in a power series in the wavelength and retaining only the first term of this expansion[1]. However, this derivation is not rigorous because the power series generally does not converge (it is a so-called asymptotic series).

Although it is possible to incorporate polarization into geometrical optics, this is not standard theory and we will not consider polarization effects in this chapter.

2Principle of Fermat¶

The starting point of the treatment of geometrical optics is the

The speed of light in a material with refractive index , is , where m/s is the speed of light in vacuum. At the time of Fermat, the conviction was that the speed of light must be finite, but nobody could suspect how incredibly large it actually is. In 1676 the Danish astronomer Ole Römer computed the speed from inspecting the eclipses of a moon of Jupiter and arrived at an estimate that was only 30% too low.

Let , be a ray with the length parameter. The ray links two points and . Suppose that the refractive index varies with position: . Over the infinitesimal distance from to , the speed of the light is

Hence the time it takes for light to go from to is:

and the total time to go from to is:

where is the distance along the ray from S to P. The optical path length [m] of the ray between S and P is defined by:

So the OPL is the distance weighted by the refractive index.

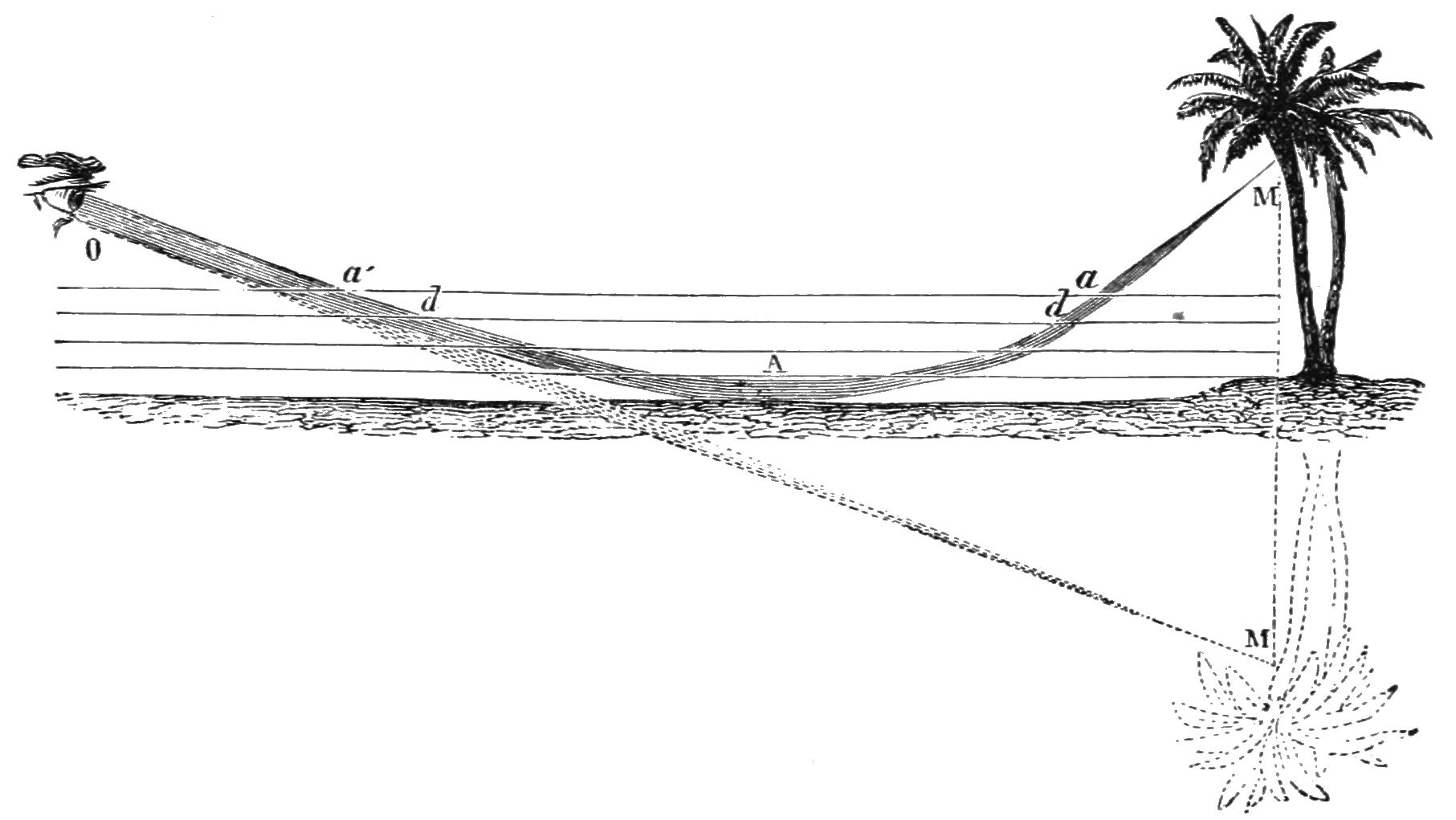

Figure 2:Because the temperature close to the ground is higher, the refractive index is lower there. Therefore the rays bend upwards, creating a mirror image of the tree below the ground. (From Popular Science Monthly Volume 5, Public Domain, link).

Remark. Actually, Fermat’s principle as formulated above is not complete. There are circumstances that a ray can take two paths between two points that have different travel times. Each of these paths then corresponds to a minimum travel time compared to nearby paths, so the travel time is in general a local minimum. An example is the reflection by a mirror discussed in the following section.

3Some Consequences of Fermat’s Principle¶

Homogeneous matter

In homogeneous matter, the refractive index is constant and therefore paths of shortest OPL are straight lines. Hence in homogeneous matter rays are straight lines.

Inhomogeneous matter

When the refractive index is a function of position such as air with a temperature gradient, the rays bend towards regions of higher refractive index. In the case of Figure 2 for example, the ray from the top of the tree to the eye of the observer passes on a warm day close to the ground because there the temperature is higher and hence the refractive index is smaller. Although the curved path is longer than the straight path, the total travel time of the light is less because near the ground the light speed is higher (since the refractive index is smaller). The observer gets the impression that the tree is upside down under the ground.

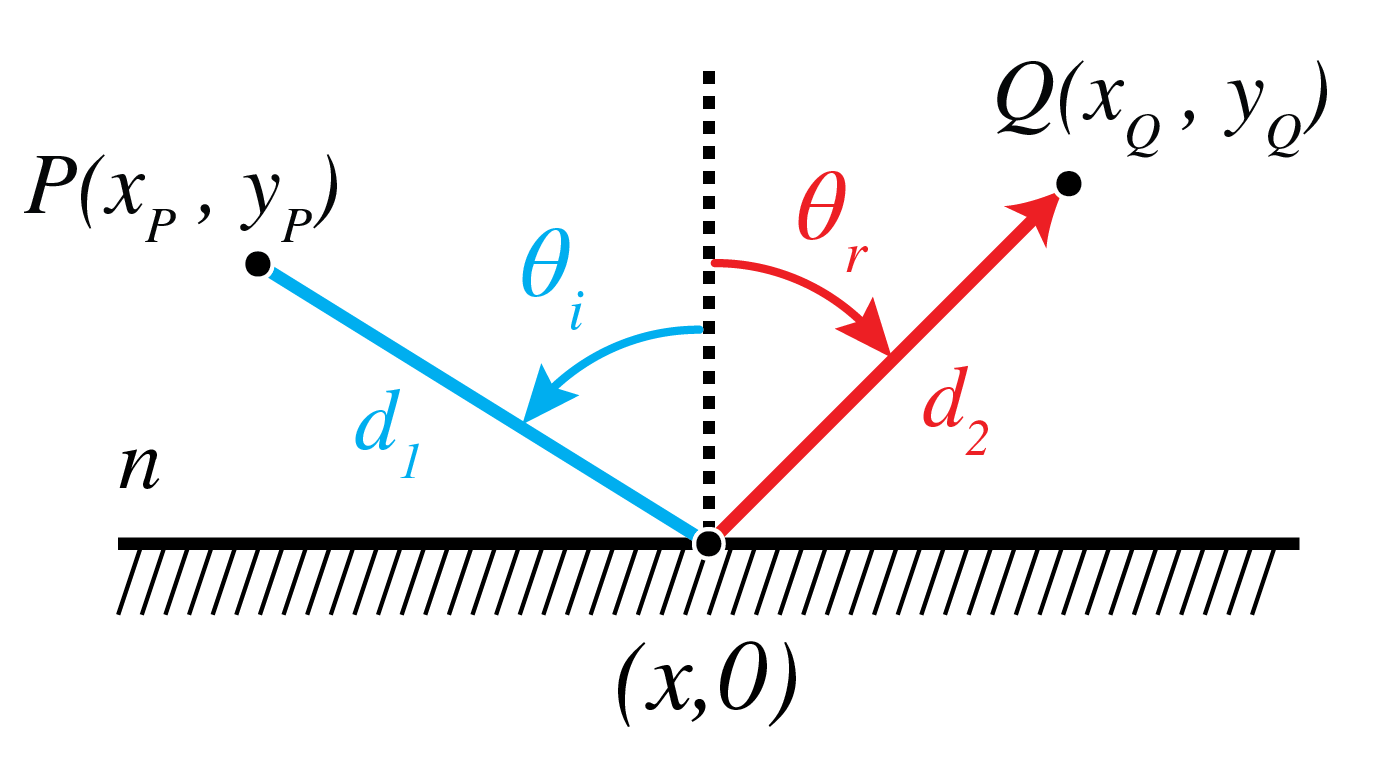

Law of reflection

Consider the mirror shown in Figure 3. Since the medium above th mirror is homogeneous, a ray from point can end up in in two ways: by going along a straight line directly from to or alternatively by straight lines via the mirror. Both possibilities have different path lengths and hence different travel times, and hence both are local minima mentioned at the end of the previous section. We consider here the path by means of reflection by the mirror. Let the -axis be the intersection of the mirror and the plane through the points and and perpendicular to the mirror. Let the -axis be normal to the mirror. Let and be the coordinates of and , respectively. If is the point where a ray from to hits the mirror, the travel time of that ray is

where is the refractive index of the medium in . According to Fermat’s Principle, the point should be such that the travel time is minimum, i.e.

Hence

or

where and are the angles of incidence and reflection as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3:Ray from to via the mirror.

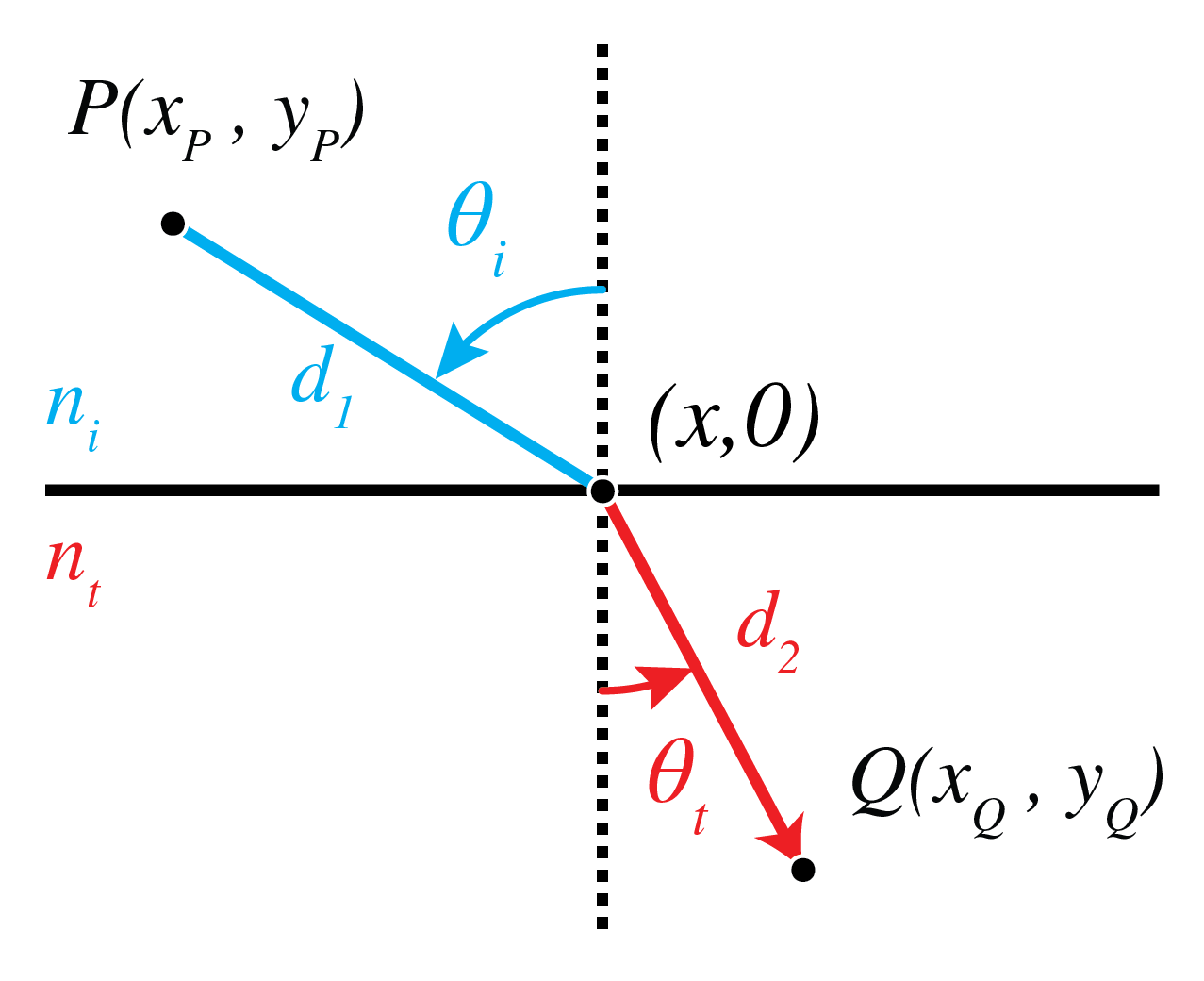

Snell’s law of refraction

Next, we consider refraction at an interface. Let be the interface between a medium with refractive index in and a medium with refractive index in . We use the same coordinate system as in the case of reflection above. Let and with and be the coordinates of two points and are shown in Figure 4. What path will a ray follow that goes from to ? Since the refractive index is constant in both half spaces, the ray is a straight line in both media. Let be the coordinate of the intersection point of the ray with the interface. Then the travel time is

The travel time must be minimum, hence there must hold

where the travel time has been multiplied by the speed of light in vacuum. Eq. (10) implies

where and are the angles between the ray and the normal to the surface in the upper half space and the lower half space, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4:Ray from to refracted by an interface.

Hence we have derived the law of reflection and Snell’s law from Fermat’s principle. In chapter.basics the reflection law and Snell’s law have been derived by a different method, namely from the continuity of the tangential electromagnetic field components at the interface.

4Perfect Imaging by Conic Sections¶

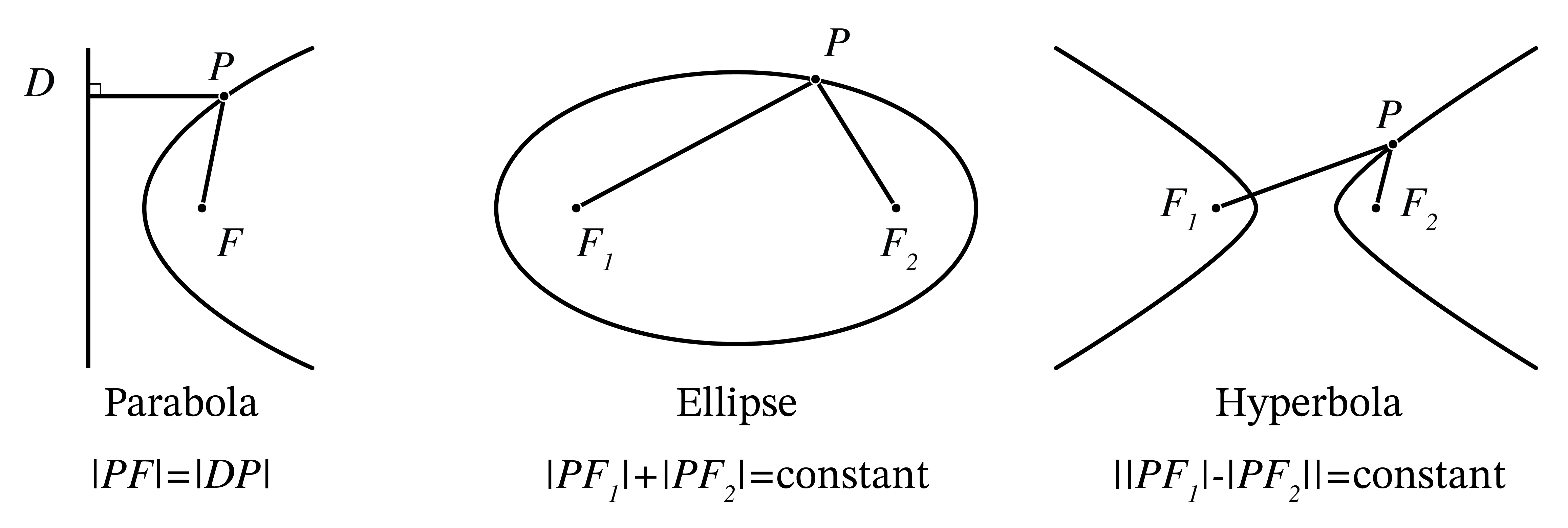

In this section, the conic sections ellipse, hyperbole and parabola are important. In Figure 6 their definitions are shown as a quick reminder[3].

Geometric construction of conic sections (ellipse, hyperbola, and parabola) showing their traditional definitions. The ellipse is the locus of points with constant sum of distances to two foci, the hyperbola has a constant difference of distances, and the parabola maintains equal distances to a focus and a directrix.

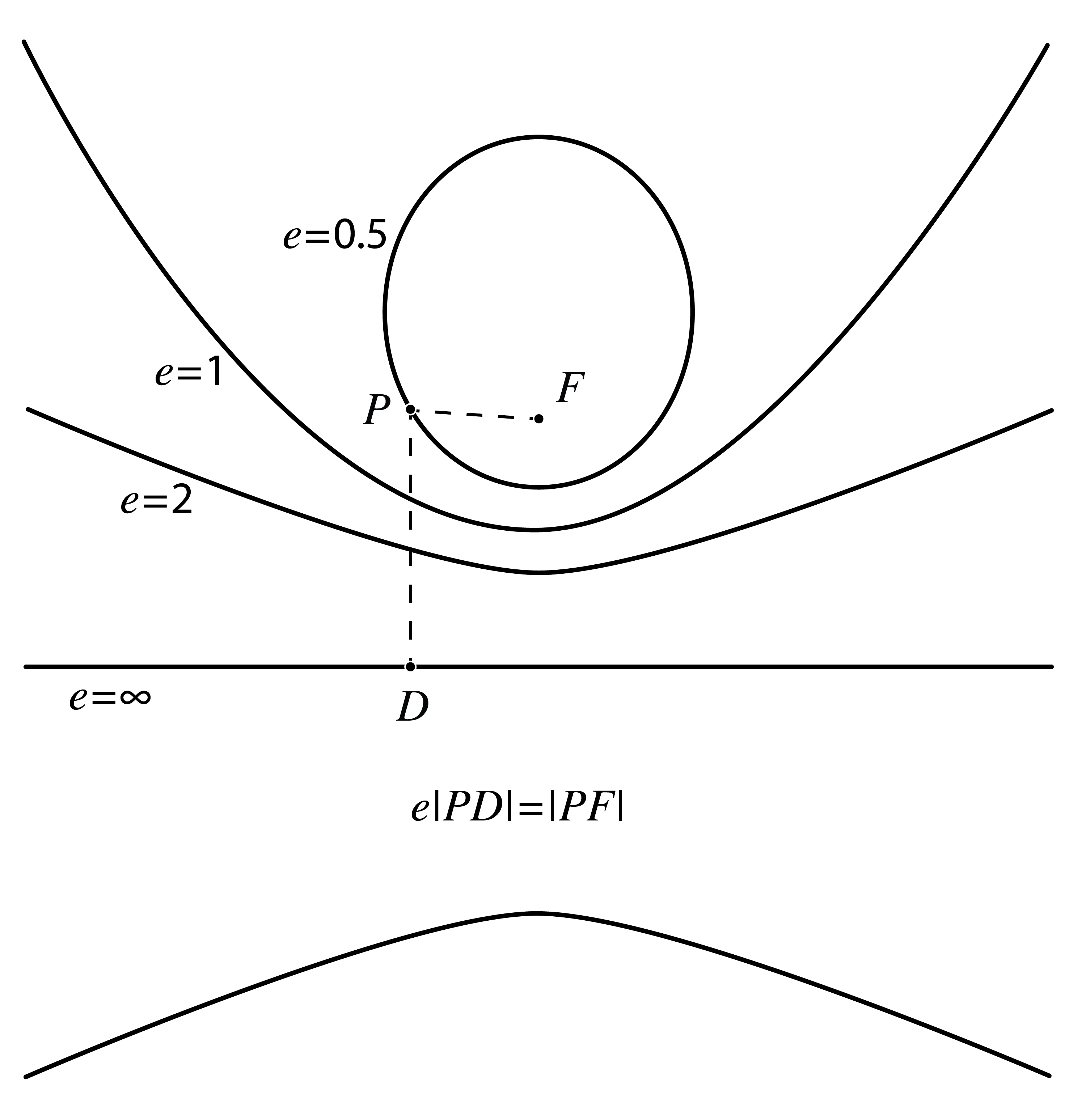

Figure 6:Overview of conic sections. The lower figure shows a definition that unifies the three definitions in the figure above by introducing a parameter called the eccentricity . The point is the focus and the line is the directrix of the conic sections.

We start with explaining what in geometrical optics is meant by perfect imaging. Let be a point source. The rays perpendicular to the spherical wave fronts emitted by radially fan out from . Due to objects such as lenses etc. the spherical wave fronts are deformed and the direction of the ray are made to deviate from the radial propagation direction. When there is a point and a cone of rays coming from point and all rays in that cone intersect in point , then by Fermat’s principle, all these rays have traversed paths of minimum travel time. In particular, their travel times are equal and therefore they all add up in phase when they arrive in . Hence at there is a high light intensity. Hence, if there is a cone of rays from point which all intersect in a point as shown in Figure 7, point is called the perfect image of . By reversing the direction of the rays, is similarly a perfect image of . The optical system in which this happens is called stigmatic for the two points and .

Figure 7:Perfect imaging: a cone of rays which diverge from and all intersect in point . The rays continue after .

Remark. The concept of a perfect image point exists only in geometrical optics. In reality finite apertures of lenses and other imaging systems cause diffraction due to which image points are never perfect but blurred.

We summarize the main examples of stigmatic systems.

1. Perfect focusing and imaging by refraction. A parallel bundle of rays propagating in a medium with refractive index can be focused into a point in a medium . If , the interface between the media should be a hyperbole with focus , whereas if the interface should be an ellipse with focus . By reversing the rays we obtain perfect collimation. Therefore, a point in air can be perfectly imaged onto a point in air by inserting a piece of glass in between them with hyperbolic surfaces. These properties are derived in Problem 2.2.

2. Perfect focusing of parallel rays by a mirror. A bundle of parallel rays in air can be focused into a point by a mirror of parabolic shape with as focus. This is derived in Problem 2.3. By reversing the arrows, we get (within geometrical optics) a perfectly parallel beam. Parabolic mirrors are used everywhere, from automobile headlights to radio telescopes.

Remark.

Although we found that conic surfaces give perfect imaging for a certain pair of points, other points do not have perfect images in the sense that for a certain cone of rays, all rays are refracted (or reflected) to the same point.

5Gaussian Geometrical Optics¶

We have seen that, although by using lenses or mirrors which have surfaces that are conic sections we can perfectly image a certain pair of points, for other points the image is not perfect. The imperfections are caused by rays that make larger angles with the optical axis, i.e. with the symmetry axis of the system. Rays for which these angles are small are called paraxial rays. Because for paraxial rays the angles of incidence and transmission at the surfaces of the lenses are small, the sine of the angles in Snell’s Law are replaced by the angles themselves:

This approximation greatly simplifies the calculations. When only paraxial rays are considered, one may replace any surface by a sphere with the same curvature at its vertex. Errors caused by replacing a surface by a sphere are of second order in the angles the ray makes with the optical axis and hence are insignificant for paraxial rays. Spherical surfaces are not only more simple in the derivations but they are also much easier to manufacture. Hence in the optical industry spherical surfaces are used a lot. To reduce imaging errors caused by non-paraxial rays one applies two strategies: 1. adding more spherical surfaces; 2 replacing one of the spherical surfaces (typically the last before image space) by a non-sphere.

5.1Gaussian Imaging by a Single Spherical Surface¶

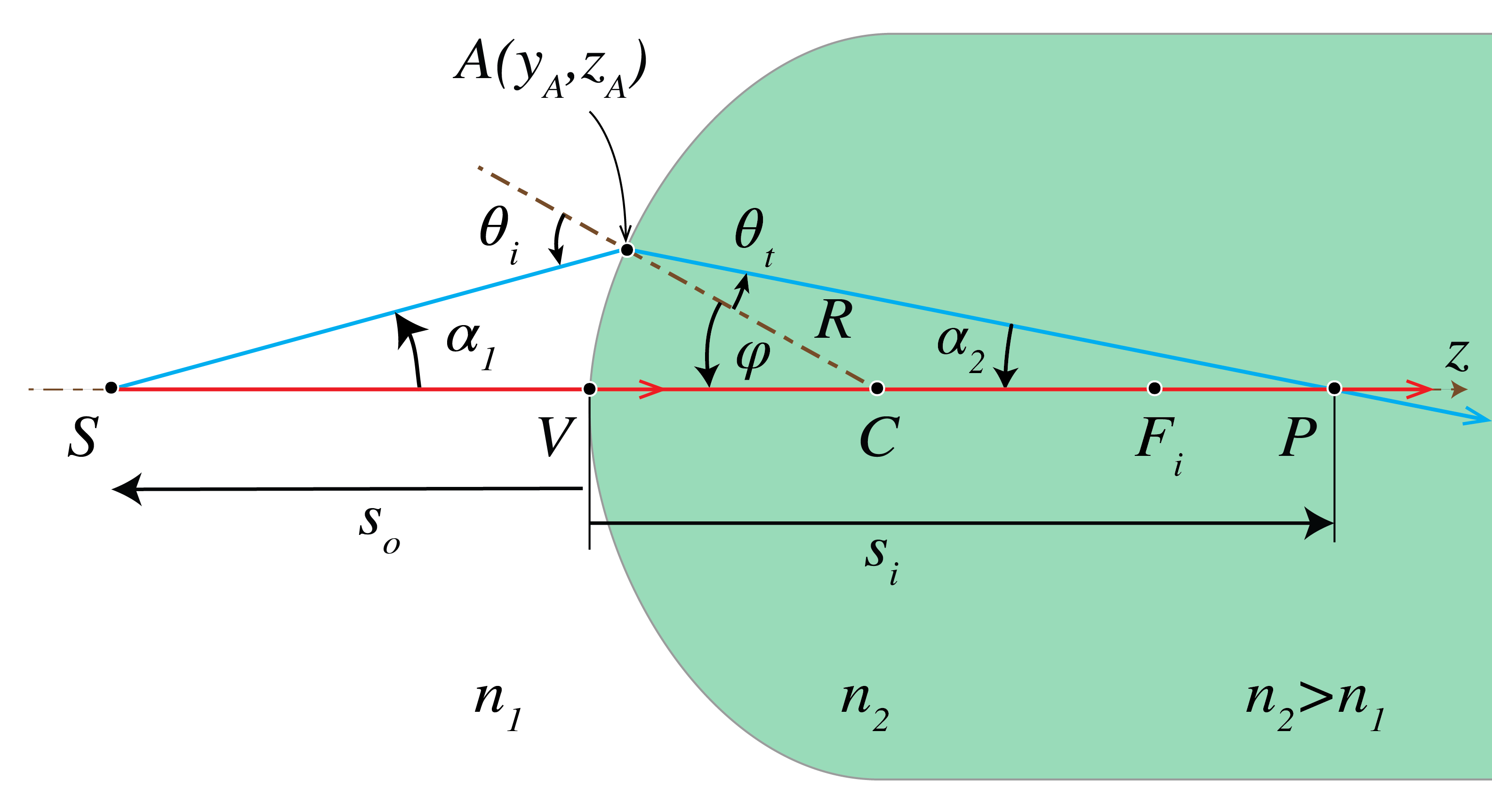

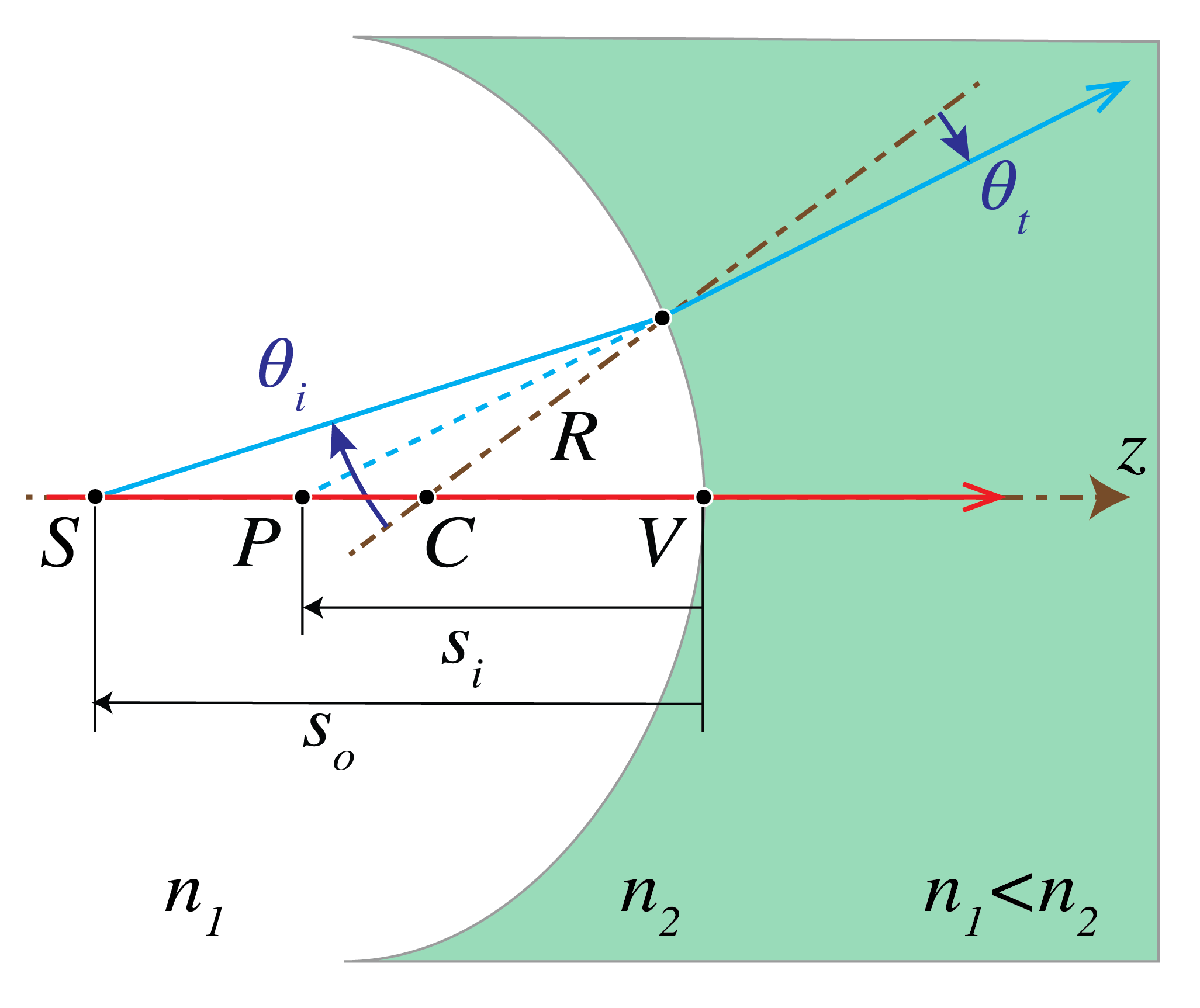

We will first show that within Gaussian optics a single spherical surface between two media with refractive indices images all points perfectly (Figure 8). The sphere has radius and center which is inside medium 2. We consider a point object to the left of the surface. We draw a ray from perpendicular to the surface. The point of intersection is . Since for this ray the angle of incidence with the local normal on the surface vanishes, the ray continues into the second medium without refraction and passes through the center of the sphere. Next we draw a ray that hits the spherical surface in some point and draw the refracted ray in medium 2 using Snell’s law in the paraxial form Eq. (12). Note that the angles of incidence and transmission must be measured with respect to the local normal at , i.e. with respect to . We assume that this ray intersects the first ray in point . We will show that within the approximation of Gaussian geometrical optics, all rays from pass through . Furthermore, with respect to a coordinate system with origin at , the -axis pointing from to and the -axis positive upwards as shown in Figure 8, we have:

where

is called the power of the surface and where and are the -coordinates of and , respectively, hence and in Figure 8.

Figure 8:Imaging by a spherical interface between two media with refractive indices .

Proof.

It suffices to show that is independent of the ray, i.e. of . We will do this by expressing into and showing that the result is independent of . Let and be the angles of the rays and with the -axis as shown in Figure 8. Let be the angle of incidence of ray with the local normal on the surface and be the angle of refraction. By considering the angles in triangle we find

Similarly, from we find

By substitution into the paraxial version of Snell’s Law Eq. (12), we obtain

Let and be the coordinates of point . Since and we have

Furthermore,

which is small for paraxial rays. Hence,

because it is second order in and therefore is neglected in the paraxial approximation. Then, Eq. (18) becomes

By substituting Eq. (21) and Eq. (19) into Eq. (17) we find

or

which is Eq. (13). It implies that , and hence , is independent of , i.e. of the ray chosen. Therefore, is a perfect image within the approximation of Gaussian geometrical optics.

When , the incident rays are parallel to the -axis in medium 1 and the corresponding image point is called the second focal point or image focal point. Its -coordinate is given by:

and its absolute value (it is negative when ) is called the second focal length or image focal length. When , the rays after refraction are parallel to the -axis and we get . The object point for which the rays in the medium 2 are parallel to the -axis is called the first focal point or object focal point . Its -coordinate is:

The absolute value of is called the front focal length or object focal length.

With Eq. (24) and Eq. (25), Eq. (13) can be rewritten as:

5.2Virtual Images and Virtual Objects of a Single Spherical Surface¶

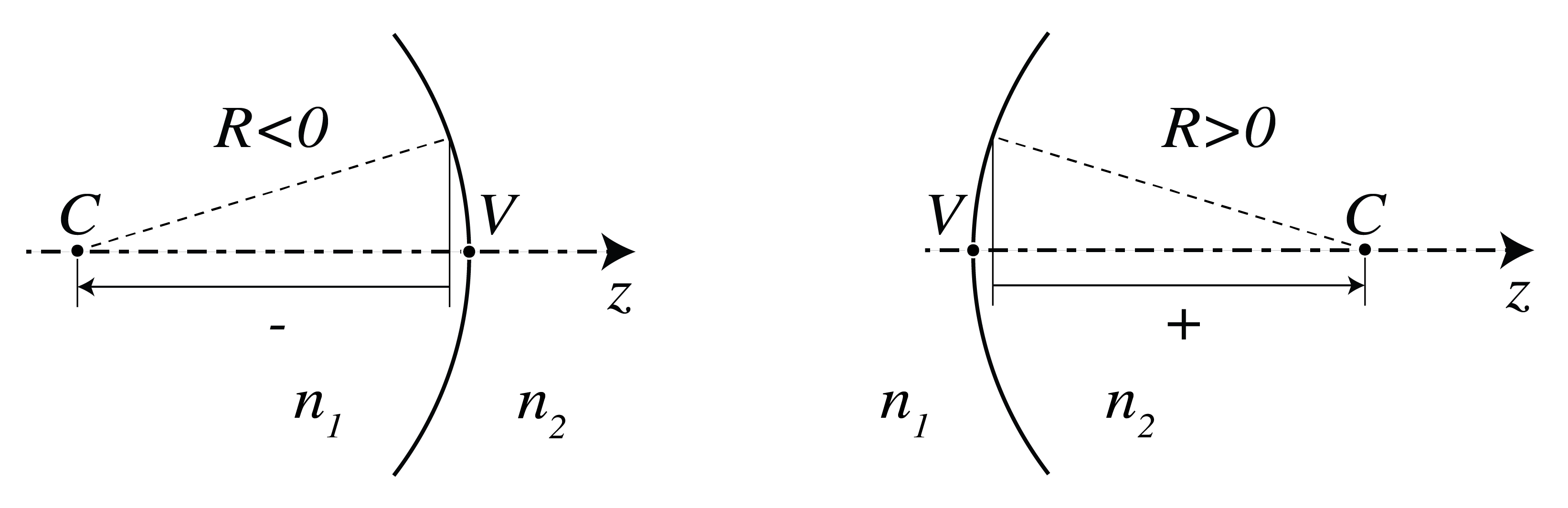

If we adopt the sign convention listed in Table 1 below, it turns out that Eq. (13) holds generally. So far we have considered a convex surface of which the center is to the right of the surface, but Eq. (13) applies also to a concave surface of which the center is to the left of the surface, provided that the radius is chosen negative. The convention for the sign of the radius is illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9:Sign convention for the radius of a spherical surface

If the power given by Eq. (14) is positive, then the surface makes bundles of incident rays convergent or less divergent. If the power is negative, incident bundles are made divergent or less convergent. The power of the surface can be negative because of two reasons:

>0 and , or

<0 and , but the effect of the two cases is the same. For any object to the left of the surface: , Eq. (26) and a negative power imply that , which suggests that the image is to the left of the surface. Indeed, in both Figs. the diverging ray bundle emitted by S is made more strongly divergent by the surface. By extending these rays in image space back to object space (without refraction at the surface), they are seen to intersect in a point to the left of the surface. This implies that for an observer at the right of the surface it looks as if the diverging rays in image space are emitted by . Because there is no actual concentration of light intensity at , it is called a virtual image, in contrast with the real images that occur to the right of the surface and where there is an actual concentration of light energy. We have in this case and , which means that the object and image focal points are to the right and left, respectively, of the surface.

Note that also when the power is positive, a virtual image can occur, namely when the object is in between the object focal point and the surface. Then the bundle of rays from S is so strongly diverging that the surface can not convert it into a convergent bundle and hence again the rays in image space seem to come from a point to the left of the surface. This agrees with the fact that when and , Eq. (26) implies that .

Figure 10:Imaging by a concave surface () with . All image points are to the left of the surface, i.e. are virtual ().

Finally we look at a case that there is a bundle of convergent rays incident from the left on the surface which when extended into the right medium without refraction at the surface, would intersect in a point . Since this point is not actually present, it is called a virtual object point, in contrast to real object points which are to the left of the surface. The coordinate of a virtual object point is positive: . One may wonder why we look at this case. The reason is that if we have several spherical surfaces behind each other, we can compute the image of an object point by first determining the intermediate image by the most left surface and then use this intermediate image as the object for the next surface and so on. In such a case, it can easily happen that an intermediate image is to the right of the next surface and hence is a virtual object for that surface. In the case of Figure 11 at the left, the power is positive, hence the convergent bundle of incident rays is made even more convergent which leads to a real image point. Indeed when and then Eq. (13) implies that always . At the right of Figure 11 the power is negative but is not sufficiently strong to turn the convergent incident bundle into a divergent bundle. So the image is still real. However, the image will be virtual when the virtual object is to the right of (which in this case is to the right of the surface) since then the bundle of rays converges so weakly that the surface turns is into a divergent bundle.

Figure 11:Imaging of a virtual object by a spherical interface with between two media with refractive indices (left) and (right).

In conclusion: provided the sign convention listed in Table 1 is used, formula Eq. (13) can always be used to determine the image of a given object by a spherical surface.

The convention for , , , follows from the fact that these are -coordinates with the origin at vertex of the spherical surface (or the center of the thin lens) and the positive -axis is pointing to the right. The convention for the -coordinate follows from the fact that the -axis is positive upwards.

Table 1:Sign convention for spherical surfaces and thin lenses

| quantity | positive | negative |

|---|---|---|

| , . , | corresponding point is to the right of vertex | corresponding point is to left of vertex |

| , | object, image point above optical axis | object, image point below optical axis |

| center of curvature right of vertex | center of curvature left of vertex | |

| Refractive index ambient medium of a mirror | before reflection | after reflection |

5.3Stops¶

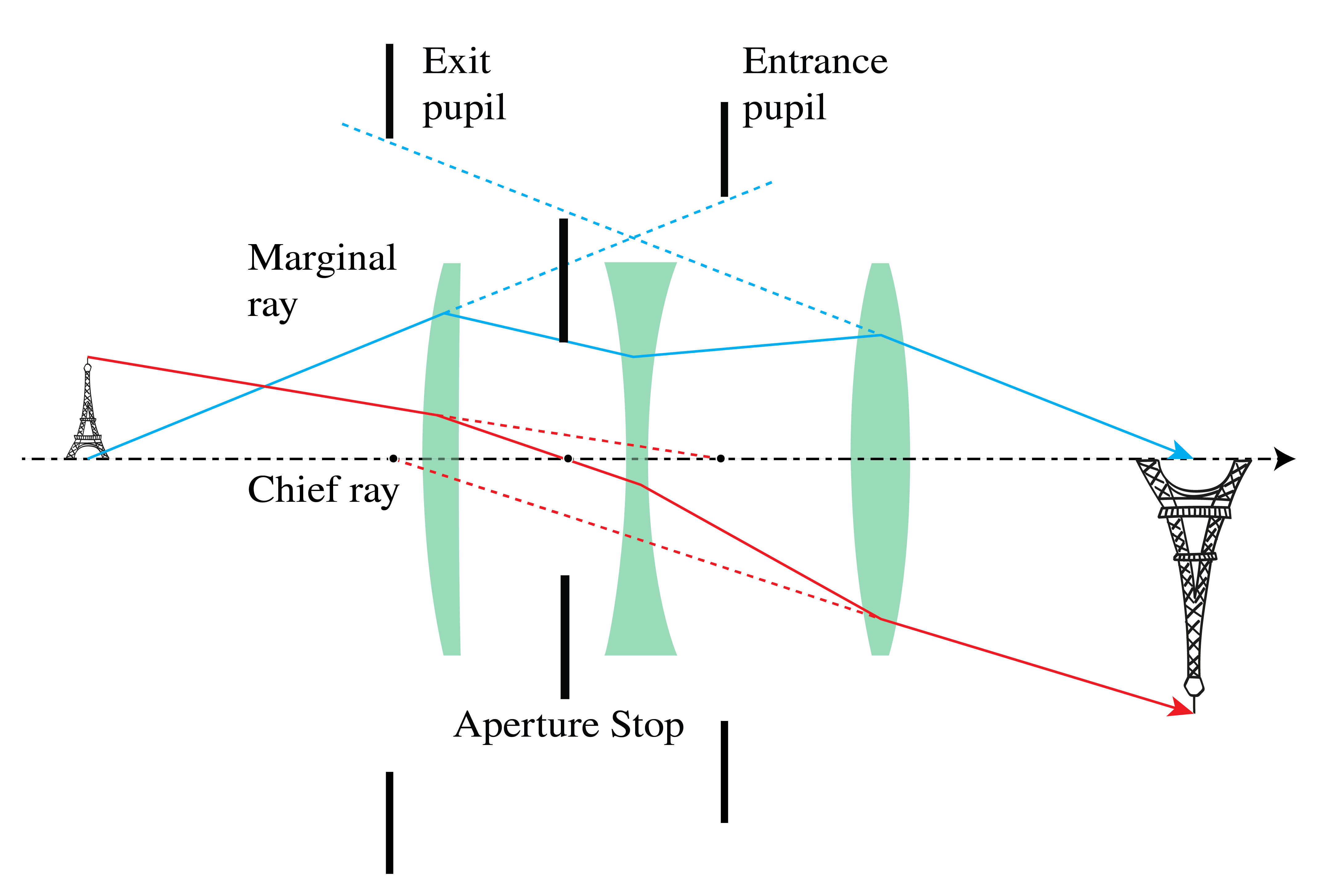

An element such as the rim of a lens or a diaphragm which determines the set of rays that can contribute to the image, is called the aperture stop. An ordinary camera has a variable diaphragm.

The entrance pupil is the image of the aperture stop by all elements to the left of the aperture stop. In constructing the entrance pupil, rays are used which propagate from the right to the left. The image can be real or virtual. If there are no lenses between object and aperture stop, the aperture stop itself is the entrance pupil. Similarly, the exit pupil is the image of the aperture stop by all elements to the right of it. This image can be real or virtual. The entrance pupil determines for a given object the cone of rays in object space that contribute to the image, while the cone of rays leaving the exit pupil are those taking part in the image formation pupil (see Figure 12).

For any object point, the chief ray is the ray in the cone that passes through the center of the entrance pupil, and hence also through the centers of the aperture stop and the exit pupil. A marginal ray is the ray that for an object point on the optical axis passes through the rim of the entrance pupil (and hence also through the rims of the aperture stop and the exit pupil).

For a fixed diameter of the exit pupil and for given , the magnification of the system is according to the transverse magnification and Newton’s lens equation (see the Ray Matrix chapter) given by . It follows that when is increased, the magnification increases. A larger magnification means a lower energy density, hence a longer exposure time, i.e. the speed of the lens is reduced. Camera lenses are usually specified by two numbers: the focal length , measured with respect to the exit pupil and the diameter of the exit pupil. The -number is the ratio of the focal length to this diameter:

For example, f-number means . Since the exposure time is proportional to the square of the f-number, a lens with f-number 1.4 is twice as fast as a lens with f-number 2.

Figure 12:Aperture stop (A.S.) between the second and third lens, with entrance pupil and exit pupil (in this case these pupils are virtual images of the aperture stop). Also shown are the chief ray and the marginal ray.

6Beyond Gaussian Geometrical Optics¶

6.1Aberrations¶

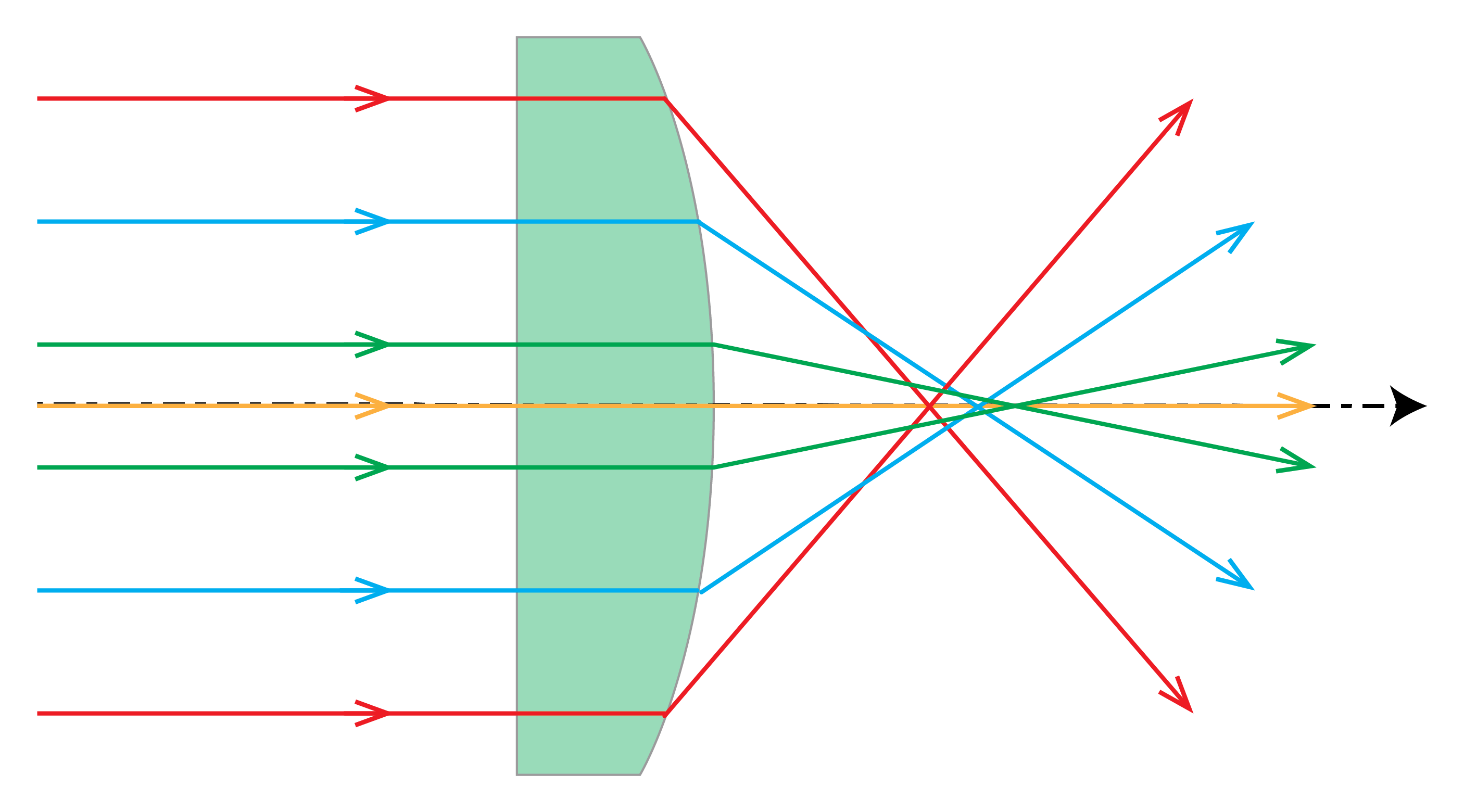

For designing advanced optical systems Gaussian geometrical optics is not sufficient. Instead non-paraxial rays, and among them also non-meridional rays, must be traced using software based on Snell’s Law with the sine of the angles of incidence and refraction. Often many thousands of rays are traced to evaluate the quality of an image. It is then found that in general the non-paraxial rays do not intersect at the ideal Gaussian image point. Instead of a single spot, a spot diagram is found which is more or less confined. The deviation from an ideal point image is quantified in terms of aberrations. One distinguishes between monochromatic and chromatic aberrations. The latter are caused by the fact that the refractive index depends on wavelength. Recall that in paraxial geometrical optics Snell’s Law Eq. (11) is replaced by: , i.e. and are replaced by the linear terms. If instead one retains the first two terms of the Taylor series of the sine, the errors in the image can be quantified by five monochromatic aberrations, the so-called primary or * Seidel aberrations*. The best known is spherical aberration, which is caused by the fact that for a convergent spherical lens, the rays that make a large angle with the optical axis are focused closer to the lens than the paraxial rays (see Figure 13).

Figure 13:Spherical aberration of a planar-convex lens.

Distortion is one of the five primary aberrations. It causes deformation of images due to the fact that the magnification depends on the distance of the object point to the optical axis.

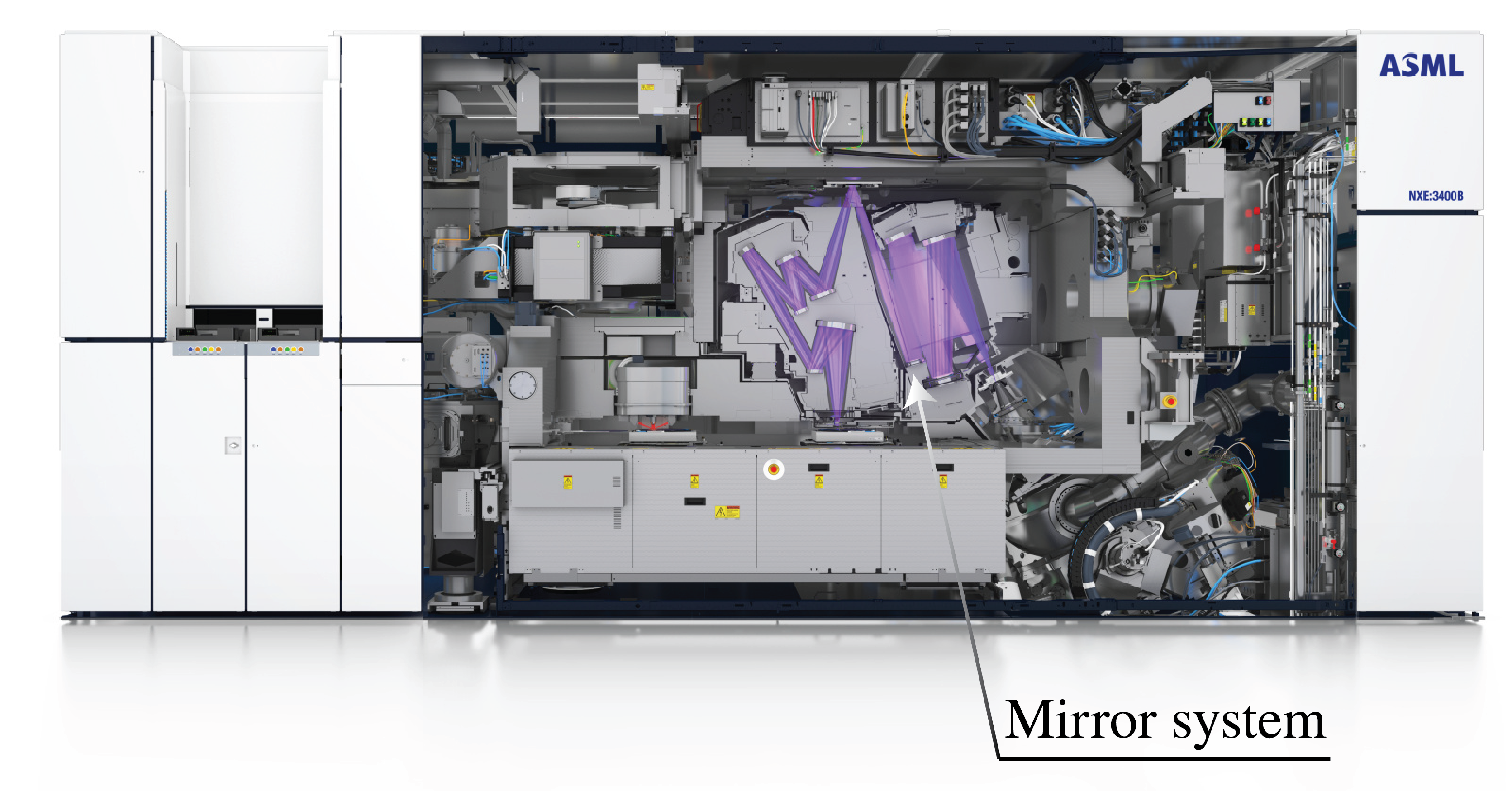

For high-quality imaging, the aberrations have to be reduced by adding more lenses and optimizing the curvatures of the surfaces, the thicknesses of the lenses and the distances between them. For high quality systems, a lens with an aspherical surface is sometimes used. Systems with very small aberrations are extremely expensive, in particular if the field of view is large, as is the case in lithographic imaging systems used in the manufacturing of integrated circuits as shown in the lithographic system in Figure 14.

A comprehensive treatment of aberration theory can be found in Braat et al.[4].

Figure 14:The EUV stepper TWINSCAN NXE:3400B.Lithographic lens system for DUV (192 nm), costing more than € 500.000. Ray paths are shown in purple. The optical system consists of mirrors because there are no suitable lenses for this wavelength (Courtesy of ASML).

6.2Diffraction¶

According to a generally accepted criterion formulated first by Rayleigh, aberrations start to deteriorate images considerably if they cause path length differences of more than a quarter of the wavelength. When the aberrations are less than this, the system is called diffraction limited.

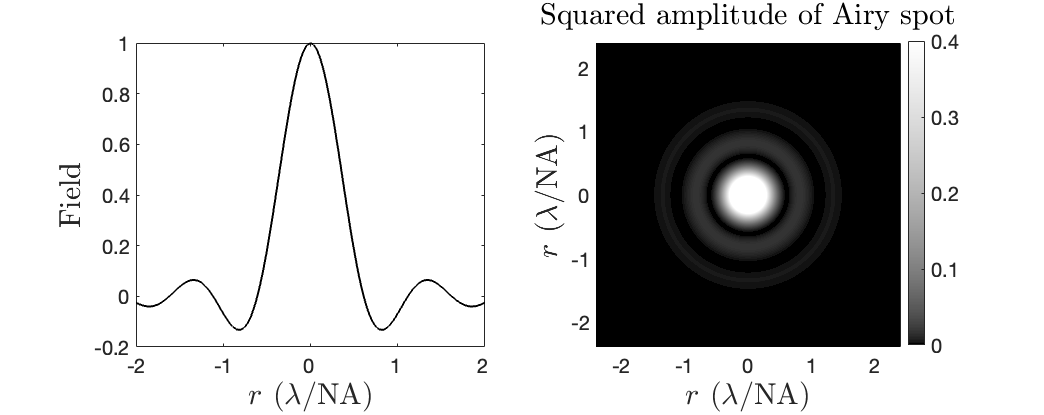

Figure 15:Left: cross section of the field of the Airy pattern. Right: intensity pattern of the Airy pattern.

Even if the wave transmitted by the exit pupil would be perfectly spherical (no aberrations), the wave front consists of only a circular section of a sphere since the field is limited by the aperture. An aperture causes diffraction, i.e. bending and spreading of the light. When one images a point object on the optical axis, diffraction causes inevitable blurring given by the so-called Airy spot, as shown in Figure 15. The Airy spot has full-width at half-maximum:

where NA is the numerical aperture (i.e. 0<NA<1) with the radius of the exit pupil and the image distance as predicted by Gaussian geometrical optics. Diffraction depends on the wavelength, and hence it cannot be described by geometrical optics, which applies in the limit of vanishing wavelength. We will treat diffraction by apertures in .

7Chapter Summary¶

Fermat’s Principle states that light follows the path of least time, forming the foundation of geometrical optics.

In Gaussian geometrical optics, the paraxial (small angle) approximation enables analytical treatment of imaging by spherical surfaces.

The Lensmaker’s Formula relates object and image distances: for a single surface.

Real images form where rays converge; virtual images form where rays appear to diverge from.

Spherical aberration limits imaging quality for rays far from the optical axis; it can be minimized using aspherical surfaces or conic sections.

Stops and pupils: The aperture stop limits the light cone; entrance and exit pupils are its images as seen from object and image space.

The f-number (f/D) characterizes the speed of a camera lens.

Geometrical optics breaks down when feature sizes approach the wavelength, leading to diffraction effects described by the Airy pattern.