Projectile motion is the motion of an object thrown or projected into the air, subject to only the acceleration of gravity. The object is called a projectile, and its path is called its trajectory. The motion of falling objects, as covered in Problem-Solving Basics for One-Dimensional Kinematics , is a simple one-dimensional type of projectile motion in which there is no horizontal movement. In this section, we consider two-dimensional projectile motion, such as that of a football or other object for which air resistance is negligible.

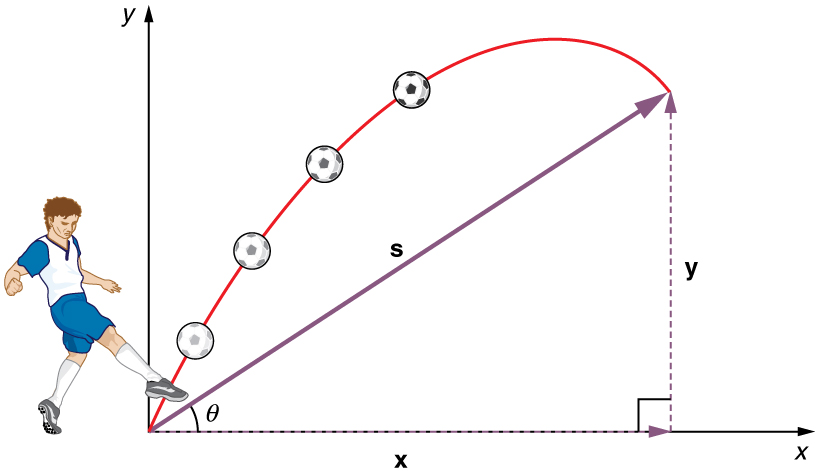

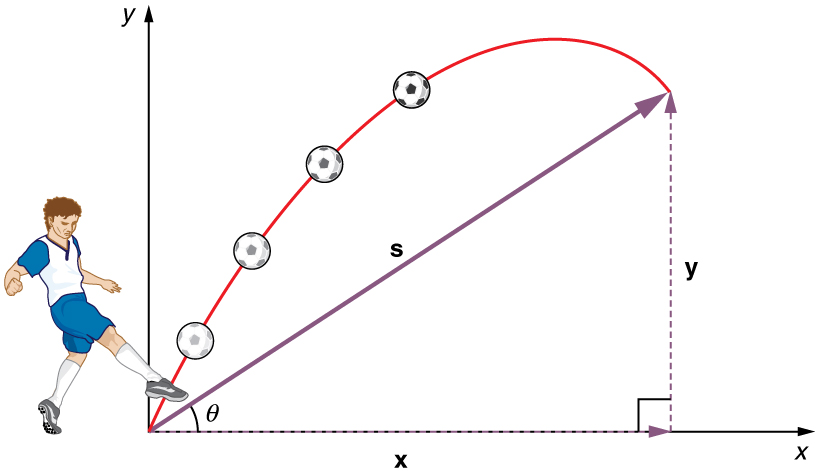

The most important fact to remember here is that motions along perpendicular axes are independent and thus can be analyzed separately. This fact was discussed in Kinematics in Two Dimensions: An Introduction , where vertical and horizontal motions were seen to be independent. The key to analyzing two-dimensional projectile motion is to break it into two motions, one along the horizontal axis and the other along the vertical. (This choice of axes is the most sensible, because acceleration due to gravity is vertical—thus, there will be no acceleration along the horizontal axis when air resistance is negligible.) As is customary, we call the horizontal axis the x-axis and the vertical axis the y-axis. Figure 1 illustrates the notation for displacement, where $\vb{s}$ is defined to be the total displacement and $\vb{x}$ and $\vb{y}$ are its components along the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively. The magnitudes of these vectors are $\mag{s}$, $\mag{x}$, and $\mag{y}$. (Note that in the last section we used the notation $\vb{A}$ to represent a vector with components $\vb{A}_{x}$ and $\vb{A}_{y}$. If we continued this format, we would call displacement $\vb{s}$ with components $\vb{s}_ {x}$ and $\vb{s}_{y}$. However, to simplify the notation, we will simply represent the component vectors as $s_x$ and $s_y$.)

Of course, to describe motion we must deal with velocity and acceleration, as well as with displacement. We must find their components along the x- and y-axes, too. We will assume all forces except gravity (such as air resistance and friction, for example) are negligible. The components of acceleration are then very simple: $a*{y}=-g=-9.80 \mss$. (Note that this definition assumes that the upwards direction is defined as the positive direction. If you arrange the coordinate system instead such that the downwards direction is positive, then acceleration due to gravity takes a positive value.) Because gravity is vertical, $a*{x}=0$. Both accelerations are constant, so the kinematic equations can be used.

Given these assumptions, the following steps are then used to analyze projectile motion:

Step 1. Resolve or break the motion into horizontal and vertical components along the x- and y-axes. These axes are perpendicular, so $A* {x}=A\cos{\theta}$ and $A*{y}=A\sin{\theta}$ are used. The magnitude of the components of displacement $\vb{s}$ along these axes are $x$ and $y$. The magnitudes of the components of the velocity $\vb{v}$ are $v_ {x}=v\cos{\theta}$ and $v_{y}=v\sin{\theta}$, where $v$ is the magnitude of the velocity and $\theta$ is its direction, as shown in Figure 2. Initial values are denoted with a subscript 0, as usual.

Step 2. Treat the motion as two independent one-dimensional motions, one horizontal and the other vertical. The kinematic equations for horizontal and vertical motion take the following forms:

Step 3. Solve for the unknowns in the two separate motions—one horizontal and one vertical. Note that the only common variable between the motions is time $t$. The problem solving procedures here are the same as for one-dimensional kinematics and are illustrated in the solved examples below.

Step 4. Recombine the two motions to find the total displacement $\vb{s}$ and velocity $\vb{v}$. Because the x- and y-motions are perpendicular, we determine these vectors by using the techniques outlined in the Vector Addition and Subtraction: Analytical Methods and employing $A=\sqrt{ A*x^2+ A_y^2}$ and $\theta ={\tan}^{-1}\left( \frac{A_y}{A_x}\right)$ in the following form, where $\theta$ is the direction of the displacement $\vb{s}$ and $\theta*{v}$ is the direction of the velocity $\vb{v}$.

Total displacement and velocity

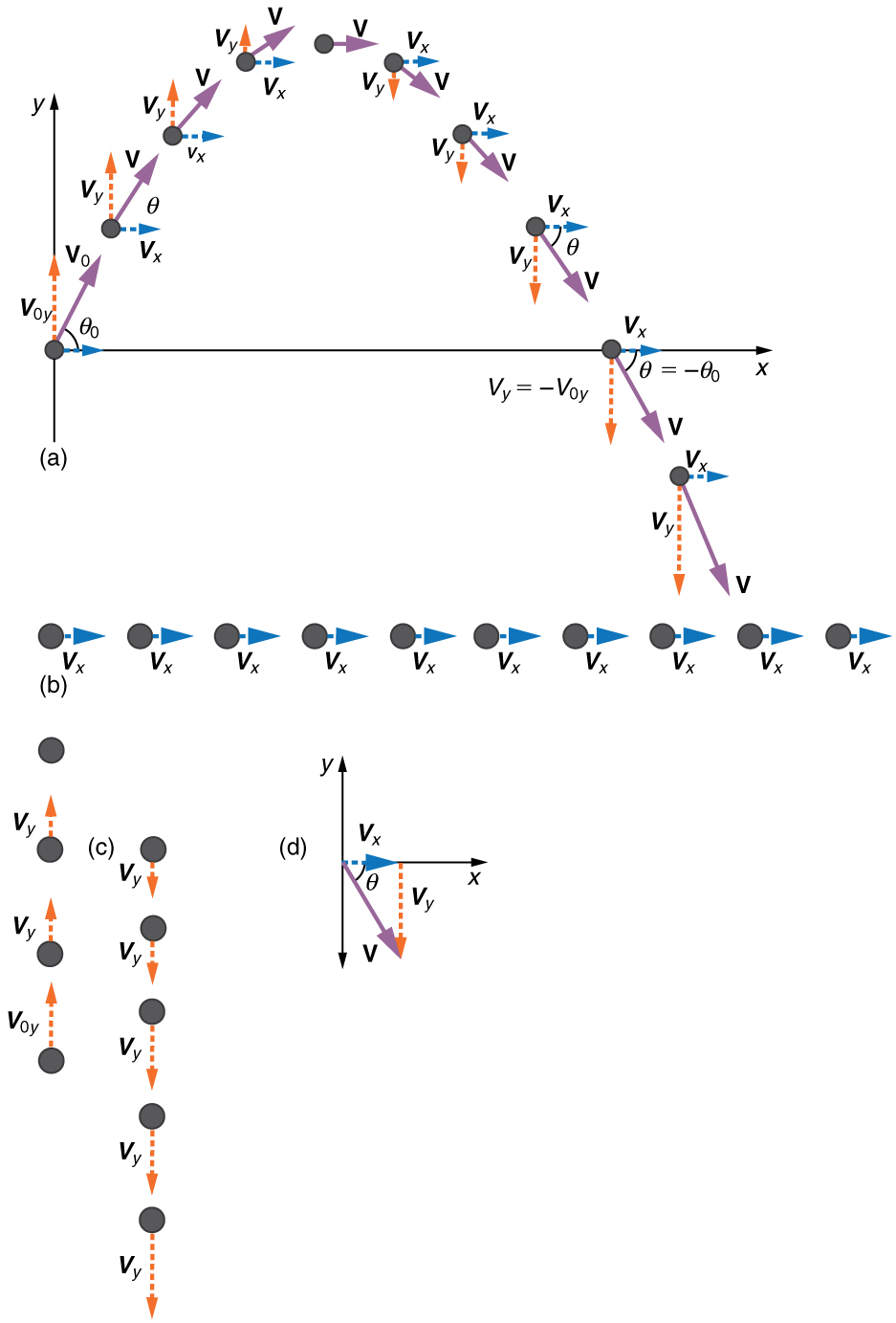

During a fireworks display, a shell is shot into the air with an initial speed of 70.0 m/s at an angle of $75.0^\circ$ above the horizontal, as illustrated in Figure 3. The fuse is timed to ignite the shell just as it reaches its highest point above the ground. (a) Calculate the height at which the shell explodes. (b) How much time passed between the launch of the shell and the explosion? (c) What is the horizontal displacement of the shell when it explodes?

Strategy

Because air resistance is negligible for the unexploded shell, the analysis method outlined above can be used. The motion can be broken into horizontal and vertical motions in which $a*{x}=0$ and $a*{y}=-g$. We can then define $x*{0}$ and $y*{0}$ to be zero and solve for the desired quantities.

Solution for (a)

By “height” we mean the altitude or vertical position $y$ above the starting point. The highest point in any trajectory, called the apex, is reached when $v_{y}=0$. Since we know the initial and final velocities as well as the initial position, we use the following equation to find $y$:

Because $y*{0}$ and $v*{y}$ are both zero, the equation simplifies to

Solving for $y$ gives

Now we must find $v_{0y}$, the component of the initial velocity in the y-direction. It is given by $v_{0y}=v_{0} \sin{\theta}$, where $v_{0y}$ is the initial velocity of 70.0 m/s, and $\theta_{0}=75.0^\circ$ is the initial angle. Thus,

and $y$ is

so that

Discussion for (a)

Note that because up is positive, the initial velocity is positive, as is the maximum height, but the acceleration due to gravity is negative. Note also that the maximum height depends only on the vertical component of the initial velocity, so that any projectile with a 67.6 m/s initial vertical component of velocity will reach a maximum height of 233 m (neglecting air resistance). The numbers in this example are reasonable for large fireworks displays, the shells of which do reach such heights before exploding. In practice, air resistance is not completely negligible, and so the initial velocity would have to be somewhat larger than that given to reach the same height.

Solution for (b)

As in many physics problems, there is more than one way to solve for the time to the highest point. In this case, the easiest method is to use $y=y* {0}+\frac{1}{2}\left(v*{0y}+v*{y}\right)t$. Because $y*{0}$ is zero, this equation reduces to simply

Note that the final vertical velocity, $v_{y}$, at the highest point is zero. Thus,

Discussion for (b)

This time is also reasonable for large fireworks. When you are able to see the launch of fireworks, you will notice several seconds pass before the shell explodes. (Another way of finding the time is by using $y=y*{0}+v* {0y}t-\frac{1}{2}g t^{2}$, and solving the quadratic equation for $t$.)

Solution for (c)

Because air resistance is negligible, $a*{x}=0$ and the horizontal velocity is constant, as discussed above. The horizontal displacement is horizontal velocity multiplied by time as given by $x=x*{0}+v*{x}t$, where $x*{0}$ is equal to zero:

where $v_{x}$ is the x-component of the velocity, which is given by $v_{x}=v_ {0}\cos{\theta_{0}}$. Now,

The time $t$ for both motions is the same, and so $x$ is

Discussion for (c)

The horizontal motion is a constant velocity in the absence of air resistance. The horizontal displacement found here could be useful in keeping the fireworks fragments from falling on spectators. Once the shell explodes, air resistance has a major effect, and many fragments will land directly below.

In solving part (a) of the preceding example, the expression we found for $$ y

$is valid for any projectile motion where air resistance is negligible. Call the maximum height$ y=h $$; then,

This equation defines the maximum height of a projectile and depends only on the vertical component of the initial velocity.

It is important to set up a coordinate system when analyzing projectile motion. One part of defining the coordinate system is to define an origin for the $x$ and $y$ positions. Often, it is convenient to choose the initial position of the object as the origin such that $x_{0}=0$ and $y_{0}=0$. It is also important to define the positive and negative directions in the $x$ and $y$ directions. Typically, we define the positive vertical direction as upwards, and the positive horizontal direction is usually the direction of the object’s motion. When this is the case, the vertical acceleration, $g$, takes a negative value (since it is directed downwards towards the Earth). However, it is occasionally useful to define the coordinates differently. For example, if you are analyzing the motion of a ball thrown downwards from the top of a cliff, it may make sense to define the positive direction downwards since the motion of the ball is solely in the downwards direction. If this is the case, $g$ takes a positive value.

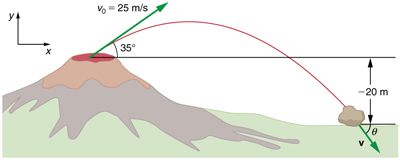

Kilauea in Hawaii is the world’s most continuously active volcano. Very active volcanoes characteristically eject red-hot rocks and lava rather than smoke and ash. Suppose a large rock is ejected from the volcano with a speed of 25.0 m/s and at an angle $35.0^\circ$ above the horizontal, as shown in Figure 4. The rock strikes the side of the volcano at an altitude 20.0 m lower than its starting point. (a) Calculate the time it takes the rock to follow this path. (b) What are the magnitude and direction of the rock’s velocity at impact?

Strategy

Again, resolving this two-dimensional motion into two independent one-dimensional motions will allow us to solve for the desired quantities. The time a projectile is in the air is governed by its vertical motion alone. We will solve for $t$ first. While the rock is rising and falling vertically, the horizontal motion continues at a constant velocity. This example asks for the final velocity. Thus, the vertical and horizontal results will be recombined to obtain $v$ and $\theta_{v}$ at the final time $t$ determined in the first part of the example.

Solution for (a)

While the rock is in the air, it rises and then falls to a final position 20.0 m lower than its starting altitude. We can find the time for this by using

If we take the initial position $y_{0}$ to be zero, then the final position is $y=-20.0 \m$. Now the initial vertical velocity is the vertical component of the initial velocity, found from $v_{0y}=v_{0}\sin{\theta_{0}} = ( 25.0 \ms )( \sin{35.0^\circ } ) = 14.3 \ms$. Substituting known values yields

Rearranging terms gives a quadratic equation in $t$:

This expression is a quadratic equation of the form $a t^{2} + b t+c=0$, where the constants are $a=4.90$, $b=-14.3$, and $c=-20.0.$ Its solutions are given by the quadratic formula:

This equation yields two solutions: $t=3.96$ and $t=-1.03$. (It is left as an exercise for the reader to verify these solutions.) The time is $t=3.96\s$ or $-1.03\s$. The negative value of time implies an event before the start of motion, and so we discard it. Thus,

Discussion for (a)

The time for projectile motion is completely determined by the vertical motion. So any projectile that has an initial vertical velocity of 14.3 m/s and lands 20.0 m below its starting altitude will spend 3.96 s in the air.

Solution for (b)

From the information now in hand, we can find the final horizontal and vertical velocities $v_{x}$ and $v_{y}$ and combine them to find the magnitude of the velocity $\mag{v}$ and the angle $\theta_{0}$ it makes with the horizontal. Of course, $v_{x}$ is constant so we can solve for it at any horizontal location. In this case, we chose the starting point since we know both the initial velocity and initial angle. Therefore:

The final vertical velocity is given by the following equation:

where $v_{0y}$ was found in part (a) to be $14.3 \ms$. Thus,

so that

To find the magnitude of the final velocity $\mag{v}$, we combine its perpendicular components, using the following equation:

which gives

The direction $\theta_{v}$ is found from the equation:

so that

Thus,

Discussion for (b)

The negative angle means that the velocity is $50.1^\circ$ below the horizontal. This result is consistent with the fact that the final vertical velocity is negative and hence downward—as you would expect because the final altitude is 20.0 m lower than the initial altitude. ( See Figure 4.)

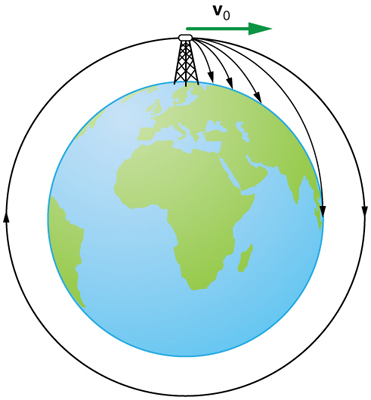

One of the most important things illustrated by projectile motion is that vertical and horizontal motions are independent of each other. Galileo was the first person to fully comprehend this characteristic. He used it to predict the range of a projectile. On level ground, we define range to be the horizontal distance $R$ traveled by a projectile. Galileo and many others were interested in the range of projectiles primarily for military purposes—such as aiming cannons. However, investigating the range of projectiles can shed light on other interesting phenomena, such as the orbits of satellites around the Earth. Let us consider projectile range further.

How does the initial velocity of a projectile affect its range? Obviously, the greater the initial speed $v*{0}$, the greater the range, as shown in Figure 5(a). The initial angle $\theta*{0}$ also has a dramatic effect on the range, as illustrated in Figure 5(b). For a fixed initial speed, such as might be produced by a cannon, the maximum range is obtained with

$\theta_ {0}=45^\circ$. This is true only for conditions neglecting air resistance. If air resistance is considered, the maximum angle is approximately $38^\circ$. Interestingly, for every initial angle except $45^\circ$, there are two angles that give the same range—the sum of those angles is $90^\circ$. The range also depends on the value of the acceleration of gravity $g$. The lunar astronaut Alan Shepherd was able to drive a golf ball a great distance on the Moon because gravity is weaker there. The range $R$ of a projectile on level ground for which air resistance is negligible is given by

where $v_{0}$ is the initial speed and $\theta_{0}$ is the initial angle relative to the horizontal. The proof of this equation is left as an end-of-chapter problem (hints are given), but it does fit the major features of projectile range as described.

When we speak of the range of a projectile on level ground, we assume that $R$ is very small compared with the circumference of the Earth. If, however, the range is large, the Earth curves away below the projectile and acceleration of gravity changes direction along the path. The range is larger than predicted by the range equation given above because the projectile has farther to fall than it would on level ground. ( See Figure 6.) If the initial speed is great enough, the projectile goes into orbit. This possibility was recognized centuries before it could be accomplished. When an object is in orbit, the Earth curves away from underneath the object at the same rate as it falls. The object thus falls continuously but never hits the surface. These and other aspects of orbital motion, such as the rotation of the Earth, will be covered analytically and in greater depth later in this text.

Once again we see that thinking about one topic, such as the range of a projectile, can lead us to others, such as the Earth orbits. In Addition of Velocities, we will examine the addition of velocities, which is another important aspect of two-dimensional kinematics and will also yield insights beyond the immediate topic.

Blast a Buick out of a cannon! Learn about projectile motion by firing various objects. Set the angle, initial speed, and mass. Add air resistance. Make a game out of this simulation by trying to hit a target.

Answer the following questions for projectile motion on level ground assuming negligible air resistance (the initial angle being neither $0^\circ$ nor $90^\circ$ ):

(a) Is the velocity ever zero?

(b) When is the velocity a minimum? A maximum?

(c) Can the velocity ever be the same as the initial velocity at a time other than at $t=0$?

(d) Can the speed ever be the same as the initial speed at a time other than at $t=0$ ?

Answer the following questions for projectile motion on level ground assuming negligible air resistance (the initial angle being neither $0^\circ$ nor $90^\circ$):

(a) Is the acceleration ever zero?

(b) Is the acceleration ever in the same direction as a component of velocity?

(c) Is the acceleration ever opposite in direction to a component of velocity?

For a fixed initial speed, the range of a projectile is determined by the angle at which it is fired. For all but the maximum, there are two angles that give the same range. Considering factors that might affect the ability of an archer to hit a target, such as wind, explain why the smaller angle (closer to the horizontal) is preferable. When would it be necessary for the archer to use the larger angle? Why does the punter in a football game use the higher trajectory?

During a lecture demonstration, a professor places two coins on the edge of a table. She then flicks one of the coins horizontally off the table, simultaneously nudging the other over the edge. Describe the subsequent motion of the two coins, in particular discussing whether they hit the floor at the same time.

A projectile is launched at ground level with an initial speed of 50.0 m/s at an angle of $30.0^\circ$ above the horizontal. It strikes a target above the ground 3.00 seconds later. What are the $x$ and $y$ distances from where the projectile was launched to where it lands?

Strategy

Resolve the initial velocity into horizontal and vertical components. Use the kinematic equations for each direction separately, with time as the common variable.

Solution

Discussion

The positive value for y indicates the target is above the launch point. The projectile travels 130 m horizontally and is 30.9 m above ground when it strikes the target.

The projectile lands at a horizontal distance of $x = 1.30 \times 10^{2} \m$ and a vertical height of $y = 30.9 \m$ above the launch point.

A ball is kicked with an initial velocity of 16 m/s in the horizontal direction and 12 m/s in the vertical direction. (a) At what speed does the ball hit the ground? (b) For how long does the ball remain in the air? (c) What maximum height is attained by the ball?

Strategy

The horizontal and vertical velocity components are given directly. Use projectile motion equations to find the time of flight, maximum height, and final velocity.

Solution

Given: $v*{0x} = 16 \ms$, $v*{0y} = 12 \ms$, $a_y = -g = -9.80 \mss$

(a) Speed when the ball hits the ground:

When the ball returns to ground level (same height as launch), by symmetry, the vertical speed has the same magnitude but opposite direction: $v_y = -12 \ms$

The horizontal velocity remains constant: $v_x = 16 \ms$

Calculate the total speed:

(b) Time in the air:

The ball rises until $v*y = 0$, then falls back. Using $v_y = v*{0y} - gt$:

Time to reach maximum height:

Total time in air (by symmetry):

(c) Maximum height:

At maximum height, $v*y = 0$. Using $v_y^2 = v*{0y}^2 - 2gy$:

Discussion

Note that the initial and final speeds are equal (20 m/s) because the ball lands at the same height from which it was kicked. This is a consequence of energy conservation.

(a) The ball hits the ground at a speed of $20 \ms$.

(b) The ball remains in the air for $2.45 \s$.

(c) The maximum height attained is $7.35 \m$.

A ball is thrown horizontally from the top of a 60.0-m building and lands 100.0 m from the base of the building. Ignore air resistance. (a) How long is the ball in the air? (b) What must have been the initial horizontal component of the velocity? (c) What is the vertical component of the velocity just before the ball hits the ground? (d) What is the velocity (including both the horizontal and vertical components) of the ball just before it hits the ground?

Strategy

Since the ball is thrown horizontally, $v\_{0y} = 0$. The vertical motion determines the time of flight, which then determines the required horizontal velocity.

Solution

Given: $y*0 = 60.0 \m$, $y = 0$, $x = 100.0 \m$, $v*{0y} = 0$

(a) Time in the air:

Using the vertical motion equation with $v\_{0y} = 0$ and taking downward as positive:

(b) Initial horizontal velocity:

Since horizontal velocity is constant:

(c) Vertical velocity at impact:

The magnitude is $34.3 \ms$ (downward).

(d) Total velocity at impact:

The horizontal component remains: $v_x = 28.6 \ms$

Magnitude:

Direction (angle below horizontal):

Discussion

The ball accelerates only in the vertical direction, so it falls faster and faster while maintaining its horizontal speed. The final velocity is directed at an angle below horizontal because the vertical component has grown larger than the horizontal component.

(a) The ball is in the air for $3.50 \s$.

(b) The initial horizontal velocity was $28.6 \ms$.

(c) The vertical velocity just before impact is $34.3 \ms$ downward.

(d) The total velocity is $44.7 \ms$ at $50.2°$ below horizontal.

(a) A daredevil is attempting to jump his motorcycle over a line of buses parked end to end by driving up a $32^\circ$ ramp at a speed of $40.0 \ms \left(144 \text{km/h}\right)$. How many buses can he clear if the top of the takeoff ramp is at the same height as the bus tops and the buses are 20.0 m long? (b) Discuss what your answer implies about the margin of error in this act—that is, consider how much greater the range is than the horizontal distance he must travel to miss the end of the last bus. (Neglect air resistance.)

Strategy

Since the takeoff and landing heights are equal, use the range equation for level ground. Calculate the range and determine how many 20.0 m buses fit within it.

Solution

Given: $v_0 = 40.0 \ms$, $\theta_0 = 32°$, bus length = 20.0 m

(a) Number of buses:

He can safely clear 7 buses.

(b) Margin of error:

The margin is the extra distance beyond 7 buses:

Discussion

The margin of error is only 7 m out of a total range of 147 m, which is about 5% of the range. This is a relatively small margin for such a dangerous stunt. Any slight reduction in speed, headwind, or error in the ramp angle could result in landing on the last bus. The stunt is risky because the actual conditions (air resistance, exact speed, ramp angle) may vary from the ideal calculated values.

(a) The daredevil can clear 7 buses.

(b) The margin of error is only 7 m, which is quite small for such a dangerous stunt, implying this act has little room for error.

An archer shoots an arrow at a 75.0 m distant target; the bull’s-eye of the target is at the same height as the release height of the arrow. (a) At what angle must the arrow be released to hit the bull’s-eye if its initial speed is 35.0 m/s? In this part of the problem, explicitly show how you follow the steps involved in solving projectile motion problems. (b) There is a large tree halfway between the archer and the target with an overhanging horizontal branch 3.50 m above the release height of the arrow. Will the arrow go over or under the branch?

Strategy

For part (a), use the range equation to find the launch angle. Since the arrow lands at the same height as release, we can use $R = \frac{v_0^2 \sin(2\theta)}{g}$. For part (b), calculate the arrow’s height at the midpoint (37.5 m horizontally) and compare it to 3.50 m.

Solution

Given: R = 75.0 m, $v_0 = 35.0 \ms$, g = 9.80 m/s²

(a) Finding the launch angle:

Step 1: Identify knowns and unknowns

Step 2: Choose the appropriate equation

Since launch and landing heights are equal, use the range equation:

Step 3: Solve for θ

Note: There are two possible angles: 18.4° and 90° - 18.4° = 71.6°. We choose the smaller angle for a flatter, faster trajectory.

(b) Height at the tree (x = 37.5 m):

First, find the time to reach x = 37.5 m:

Now find the vertical position at this time:

Since 6.24 m > 3.50 m, the arrow will go over the branch.

Discussion

The arrow reaches a height of 6.24 m at the tree, safely clearing the 3.50 m branch by about 2.7 m. The relatively low launch angle (18.4°) means the arrow travels on a flatter trajectory, which is preferred in archery for accuracy and speed. The steeper complementary angle (71.6°) would also give the same range but would result in a much longer flight time and less accuracy.

Answer

(a) The arrow must be released at an angle of 18.4° above horizontal.

(b) The arrow will go over the branch, passing 6.24 m above the ground at that point.

A rugby player passes the ball 7.00 m across the field, where it is caught at the same height as it left his hand. (a) At what angle was the ball thrown if its initial speed was 12.0 m/s, assuming that the smaller of the two possible angles was used? (b) What other angle gives the same range, and why would it not be used? (c) How long did this pass take?

Strategy

Since the ball is caught at the same height as it was thrown, we can use the range equation for level ground. The range equation gives two possible angles that produce the same range. The smaller angle gives a flatter, faster trajectory.

Solution

Given: R = 7.00 m, $v_0 = 12.0 \ms$

(a) Finding the smaller launch angle:

Use the range equation:

Solve for $\sin(2\theta)$:

(b) The other angle:

Since $\sin(2\theta) = \sin(180° - 2\theta)$, the other solution is:

This angle would not be used because:

(c) Time of flight:

First, find the vertical component of initial velocity:

At maximum height, $v_y = 0$. Time to reach maximum height:

By symmetry, total flight time:

Discussion

The short flight time (0.600 s) confirms that the smaller angle produces a quick, flat pass that minimizes the opportunity for interception. The complementary angle (75.8°) would result in a much longer flight time of about 2.4 s, which would be impractical in a fast-paced rugby match.

Answer

(a) The ball was thrown at an angle of 14.2° above horizontal.

(b) The other angle is 75.8°. This angle would not be used because it results in a much longer flight time, making the pass easier to intercept and harder to catch.

(c) The pass took 0.600 s.

Verify the ranges for the projectiles in Figure 5(a) for $\theta =45^\circ$ and the given initial velocities.

Strategy

Use the range equation for projectile motion on level ground. For an angle of 45°, the range equation simplifies because $\sin(2 \times 45°) = \sin(90°) = 1$. Calculate the range for each given initial velocity.

Solution

The range equation is:

For $\theta = 45°$:

Therefore, the range simplifies to:

For $v_0 = 30 \ms$:

For $v_0 = 40 \ms$:

For $v_0 = 50 \ms$:

Discussion

These calculations confirm the ranges shown in Figure 5(a). Notice that the range is proportional to the square of the initial velocity. This means doubling the initial velocity quadruples the range. For instance, increasing from 30 m/s to 60 m/s would increase the range from 91.8 m to about 367 m (four times as much).

The angle of 45° produces the maximum range for a given initial speed when air resistance is negligible and the launch and landing heights are equal. This is because $\sin(2\theta)$ reaches its maximum value of 1 when $2\theta = 90°$, which occurs at $\theta = 45°$.

Answer

The ranges are verified:

Verify the ranges shown for the projectiles in Figure 5(b) for an initial velocity of 50 m/s at the given initial angles.

Strategy

Use the range equation $R = \frac{v_0^2 \sin(2\theta)}{g}$ to calculate the range for each angle shown in Figure 5(b). The figure shows trajectories for angles of 15°, 45°, and 75°. We should verify that complementary angles (15° and 75°) give the same range.

Solution

Given: $v_0 = 50 \ms$, $g = 9.80 \mss$

The range equation is:

For $\theta = 15°$:

For $\theta = 45°$:

For $\theta = 75°$:

Discussion

These calculations verify the ranges shown in Figure 5(b). Notice that:

Complementary angles give equal ranges: The angles 15° and 75° are complementary (they sum to 90°) and both produce the same range of 128 m. This occurs because $\sin(30°) = \sin(150°) = 0.500$.

Maximum range at 45°: The 45° angle produces the maximum range of 255 m, which is exactly twice the range of the complementary angles.

Different trajectories, same range: Although 15° and 75° give the same horizontal range, their trajectories are very different. The 15° trajectory is low and fast, while the 75° trajectory is high and slow. In practice, the lower angle is usually preferred because it’s faster and less affected by wind.

Answer

The ranges are verified for $v_0 = 50 \ms$:

The cannon on a battleship can fire a shell a maximum distance of 32.0 km. (a) Calculate the initial velocity of the shell. (b) What maximum height does it reach? (At its highest, the shell is above 60% of the atmosphere—but air resistance is not really negligible as assumed to make this problem easier.) (c) The ocean is not flat, because the Earth is curved. Assume that the radius of the Earth is $6.37\times 10^{3}\text{km}$. How many meters lower will its surface be 32.0 km from the ship along a horizontal line parallel to the surface at the ship? Does your answer imply that error introduced by the assumption of a flat Earth in projectile motion is significant here?

Strategy

For part (a), use the range equation. Maximum range occurs at 45°. For part (b), calculate the maximum height using the vertical component of initial velocity. For part (c), use geometry to find the Earth’s curvature over the horizontal distance.

Solution

(a) Initial velocity for maximum range:

Maximum range occurs at $\theta = 45°$, where $\sin(2 \times 45°) = \sin(90°) = 1$.

The range equation becomes:

Solving for $v_0$:

(b) Maximum height:

At 45°, the vertical component of initial velocity is:

The maximum height is:

(c) Earth’s curvature effect:

For a sphere, the vertical drop from a horizontal line over distance $d$ can be approximated using the Pythagorean theorem. If $R_E$ is Earth’s radius and $d$ is the horizontal distance, the drop $h$ is:

For small $h$ compared to $R_E$, this simplifies to:

Substituting values:

Rounding to three significant figures: h = 80.0 m

Comparing to the maximum height of 8000 m:

Discussion

The shell reaches an impressive height of 8 km, which is above 60% of Earth’s atmosphere (the troposphere extends to about 11 km). At this altitude, air resistance would actually be significantly less than at sea level, making our simplified calculation somewhat more reasonable than it might first appear.

The Earth’s curvature causes an 80 m drop over the 32 km range. This is only 1% of the maximum height, so the flat Earth approximation introduces minimal error for this problem. However, for intercontinental ballistic missiles traveling thousands of kilometers, Earth’s curvature would be crucial.

Answer

(a) The initial velocity of the shell is 560 m/s (about 1.6 times the speed of sound).

(b) The maximum height reached is 8.00 × 10³ m or 8.00 km.

(c) The Earth’s surface drops 80.0 m over the 32 km distance. This is only 1% of the maximum height, so the flat Earth assumption does not introduce significant error for this problem.

An arrow is shot from a height of 1.5 m toward a cliff of height $H$. It is shot with a velocity of 30 m/s at an angle of $60^\circ$ above the horizontal. It lands on the top edge of the cliff 4.0 s later. (a) What is the height of the cliff? (b) What is the maximum height reached by the arrow along its trajectory? (c) What is the arrow’s impact speed just before hitting the cliff?

Strategy

For part (a), use the vertical motion equation to find the final height. For part (b), calculate the maximum height using the vertical component of initial velocity. For part (c), find the velocity components at impact time and combine them.

Solution

Given: $y_0 = 1.5 \m$, $v_0 = 30 \ms$, $\theta = 60°$, $t = 4.0 \s$

First, find the initial velocity components:

(a) Height of the cliff:

Using the vertical position equation:

The cliff height is H = 27.1 m.

(b) Maximum height reached:

The maximum height occurs when $v_y = 0$. Using:

Setting $v_y = 0$:

(c) Impact speed:

At impact (t = 4.0 s), the horizontal velocity remains constant:

The vertical velocity at impact:

The speed (magnitude of velocity):

Discussion

The arrow reaches a maximum height of 36.0 m, which is 8.9 m higher than the cliff top (27.1 m). This means the arrow is falling when it hits the cliff, which explains why the vertical velocity component is negative (-13.2 m/s).

The impact speed of 20.0 m/s is less than the initial speed of 30 m/s, which makes sense because the arrow is still moving upward relative to its launch point (the cliff at 27.1 m is higher than the launch height of 1.5 m by 25.6 m).

Answer

(a) The height of the cliff is 27.1 m.

(b) The maximum height reached by the arrow is 36.0 m above the ground.

(c) The arrow’s impact speed is 20.0 m/s.

In the standing broad jump, one squats and then pushes off with the legs to see how far one can jump. Suppose the extension of the legs from the crouch position is 0.600 m and the acceleration achieved from this position is 1.25 times the acceleration due to gravity, $g$. How far can they jump? State your assumptions. (Increased range can be achieved by swinging the arms in the direction of the jump.)

Strategy

First, find the launch velocity using kinematics during the acceleration phase. Then use the range equation to find the horizontal distance. Assume the optimal launch angle of 45° for maximum range.

Solution

Assumptions:

Step 1: Find the launch velocity

During the leg extension, the jumper accelerates over a distance of 0.600 m with acceleration $a = 1.25g$.

Using the kinematic equation:

Starting from rest ($v_i = 0$):

Step 2: Calculate the range

For a 45° launch angle, $\sin(2 \times 45°) = \sin(90°) = 1$, so:

Discussion

The calculated range of 1.50 m is reasonable for a standing broad jump without arm swing. Elite athletes can achieve standing broad jumps of over 3 meters, but they use techniques like:

The 45° launch angle assumption is reasonable for maximum horizontal distance. In practice, jumpers might use a slightly lower angle (around 40°) because they’re launching from a crouch position rather than from standing height, and they want to maximize forward velocity.

Answer

The jumper can achieve a range of 1.50 m, assuming a launch angle of 45° and the given conditions.

The world long jump record is 8.95 m (Mike Powell, USA, 1991). Treated as a projectile, what is the maximum range obtainable by a person if he has a take-off speed of 9.5 m/s? State your assumptions.

Strategy

Use the range equation for projectile motion. Maximum range occurs at a 45° launch angle. Compare the calculated maximum to the actual world record.

Solution

Assumptions:

Given: $v_0 = 9.5 \ms$

For maximum range at 45°:

Discussion

The calculated maximum range of 9.21 m is remarkably close to the actual world record of 8.95 m, which validates our assumptions. The slight difference (0.26 m or about 3%) can be attributed to several factors:

Launch vs. landing height: The athlete’s center of mass is higher at takeoff than at landing, which would increase the range beyond the equal-height calculation

Air resistance: At 9.5 m/s, air resistance would slightly reduce the range

The fact that the actual record is slightly less than our calculated maximum suggests that the lower launch angle (which reduces theoretical maximum range) is roughly offset by the higher launch position and body extension techniques.

Answer

With a takeoff speed of 9.5 m/s and a 45° launch angle, the maximum theoretical range is 9.21 m, assuming equal launch and landing heights and negligible air resistance. This is very close to the actual world record of 8.95 m.

Serving at a speed of 170 km/h, a tennis player hits the ball at a height of 2.5 m and an angle $\theta$ below the horizontal. The base line is 11.9 m from the net, which is 0.91 m high. What is the angle $\theta$ such that the ball just crosses the net? Will the ball land in the service box, whose service line is 6.40 m from the net?

Strategy

Convert the speed to m/s. Find the angle that makes the ball just clear the net at x = 11.9 m. Then find where the ball lands (y = 0) to check if it’s within 6.40 m from the net.

Solution

Given:

Part 1: Find the angle to just clear the net

The velocity components are (with $\theta$ below horizontal, so $v\_{0y}$ is negative):

Time to reach the net:

Height at the net:

For small angles, $\cos\theta \approx 1$:

Part 2: Where does the ball land?

Using $\theta = 6.1°$:

Find when y = 0:

Using the quadratic formula:

Horizontal distance:

Distance from net:

Since 5.3 m < 6.40 m, the ball lands inside the service box.

Discussion

The relatively small angle of 6.1° below horizontal is typical for tennis serves. The server wants to hit the ball hard (high speed) while still getting it over the net and into the service box. A steeper angle would make it easier to clear the net but harder to land in the box.

The ball lands 5.3 m from the net, well within the 6.40 m service line, with a margin of 1.1 m. This is a good serve.

Answer

The angle below horizontal is θ = 6.1°.

Yes, the ball lands in the service box at 5.3 m from the net, which is within the 6.40 m service line.

A football quarterback is moving straight backward at a speed of 2.00 m/s when he throws a pass to a player 18.0 m straight downfield. (a) If the ball is thrown at an angle of $25^\circ$ relative to the ground and is caught at the same height as it is released, what is its initial speed relative to the ground? (b) How long does it take to get to the receiver? (c) What is its maximum height above its point of release?

Strategy

The quarterback is moving backward at 2.00 m/s, so his velocity relative to the ground is -2.00 m/s in the forward direction. The ball’s velocity relative to the ground is the sum of the ball’s velocity relative to the quarterback and the quarterback’s velocity. Use the range equation to find the ball’s initial speed relative to the ground.

Solution

Given:

(a) Initial speed relative to the ground:

Let $v_0$ be the ball’s initial speed relative to the ground. The horizontal component is:

The vertical component is:

Using the range equation, we need to account for the quarterback’s motion. The time of flight is:

The range is:

Using the quadratic formula:

(b) Time to reach the receiver:

(c) Maximum height:

Discussion

The quarterback’s backward motion reduces the ball’s forward velocity relative to the ground. This requires a higher throwing speed (16.3 m/s relative to the ground) compared to what would be needed if the quarterback were stationary.

The relatively low maximum height of 2.42 m is due to the shallow 25° launch angle. This is typical for football passes, where quarterbacks prefer flatter trajectories that reach receivers quickly and are harder for defenders to intercept.

Answer

(a) The ball’s initial speed relative to the ground is 16.3 m/s.

(b) The ball takes 1.41 s to reach the receiver.

(c) The maximum height above the release point is 2.42 m.

Gun sights are adjusted to aim high to compensate for the effect of gravity, effectively making the gun accurate only for a specific range. (a) If a gun is sighted to hit targets that are at the same height as the gun and 100.0 m away, how low will the bullet hit if aimed directly at a target 150.0 m away? The muzzle velocity of the bullet is 275 m/s. (b) Discuss qualitatively how a larger muzzle velocity would affect this problem and what would be the effect of air resistance.

Strategy

First, find the launch angle needed to hit a target 100.0 m away. Then calculate where the bullet lands vertically when aimed at this same angle but for a horizontal distance of 150.0 m.

Solution

Given:

(a) Vertical deviation at 150.0 m:

Step 1: Find the sight angle for 100.0 m range

Using the range equation:

Step 2: Find time to reach 150.0 m

Step 3: Find vertical position at 150.0 m

The bullet hits 0.486 m below the target (or -0.486 m).

(b) Effects of higher muzzle velocity and air resistance:

Higher muzzle velocity:

Air resistance:

Discussion

The very small sight angle (0.372°) shows that high-velocity rifles need minimal adjustment for relatively short ranges. However, even this tiny angle causes about half a meter deviation when the target is 50% farther away than the calibrated distance.

In real scenarios with air resistance, marksmen must account for:

Modern scopes often have range-finding reticles with multiple aiming points for different distances.

Answer

(a) The bullet will hit 0.486 m below the target (or -0.486 m).

(b) A larger muzzle velocity would decrease the vertical deviation because the bullet spends less time in flight, giving gravity less time to act. Air resistance would increase the vertical deviation by slowing the bullet and prolonging its flight time.

An eagle is flying horizontally at a speed of 3.00 m/s when the fish in her talons wiggles loose and falls into the lake 5.00 m below. Calculate the velocity of the fish relative to the water when it hits the water.

Strategy

The fish initially has the same horizontal velocity as the eagle (3.00 m/s) and zero vertical velocity. Use kinematic equations to find the vertical velocity component when the fish has fallen 5.00 m, then combine with the horizontal component to find the total velocity.

Solution

Given:

Step 1: Find the vertical velocity component at impact

Using the kinematic equation:

Note: Taking up as positive, so $\Delta y = -5.00 \m$ and acceleration is $a = -g$:

Wait, let me reconsider. Taking down as positive:

Step 2: Find horizontal velocity component

The horizontal velocity remains constant (no horizontal acceleration):

Step 3: Calculate the magnitude of velocity

Step 4: Find the direction

The angle below horizontal is:

Discussion

The fish hits the water at 10.3 m/s at an angle of 73.1° below horizontal. Notice that the vertical velocity component (9.90 m/s) is much larger than the horizontal component (3.00 m/s), which is why the angle is so steep.

The fish essentially falls straight down while maintaining its initial horizontal speed. After falling 5.00 m, gravity has accelerated it to nearly 10 m/s vertically, while it still moves horizontally at 3 m/s.

Answer

The fish hits the water with a velocity of 10.3 m/s at an angle of 73.1° below horizontal, or equivalently, the velocity vector is $\vec{v} = (3.00 \ms, -9.90 \ms)$.

An owl is carrying a mouse to the chicks in its nest. Its position at that time is 4.00 m west and 12.0 m above the center of the 30.0 cm diameter nest. The owl is flying east at 3.50 m/s at an angle $30.0^\circ$ below the horizontal when it accidentally drops the mouse. Is the owl lucky enough to have the mouse hit the nest? To answer this question, calculate the horizontal position of the mouse when it has fallen 12.0 m.

Strategy

The mouse initially has the same velocity as the owl: 3.50 m/s at 30° below horizontal. Find the velocity components, then determine the time to fall 12.0 m. Use this time to calculate the horizontal distance traveled.

Solution

Given:

Step 1: Find initial velocity components

Taking east as positive x and down as positive y:

Step 2: Find the time to fall 12.0 m

Using the vertical motion equation (taking down as positive):

Using the quadratic formula:

Step 3: Calculate horizontal distance traveled

Step 4: Determine if mouse hits the nest

The mouse travels 4.23 m east from its release point. Since it was released 4.00 m west of the nest center:

Distance from nest center:

The nest has a radius of 15.0 cm (diameter 30.0 cm). Since 23 cm > 15 cm, the mouse misses the nest.

Discussion

The owl is unlucky! The mouse lands 23 cm east of the nest center, which is 8 cm beyond the edge of the nest (23 - 15 = 8 cm).

If the owl had dropped the mouse slightly earlier (when it was farther west), or if it had been flying more slowly, the mouse would have landed in the nest. The owl’s downward velocity component caused the mouse to fall faster than it would have if dropped from a horizontally flying bird, reducing the time available for horizontal travel.

Answer

The mouse lands 4.23 m east of its release point, which is 0.23 m (23 cm) east of the nest center. Since the nest has a radius of only 15 cm, the owl is not lucky — the mouse misses the nest by about 8 cm.

Suppose a soccer player kicks the ball from a distance 30 m toward the goal. Find the initial speed of the ball if it just passes over the goal, 2.4 m above the ground, given the initial direction to be $40^\circ$ above the horizontal.

Strategy

Use the projectile motion equations to relate the horizontal distance (30 m), vertical height (2.4 m), and launch angle (40°) to find the initial speed. Use the horizontal and vertical equations simultaneously.

Solution

Given:

Step 1: Express velocity components in terms of $v_0$

Step 2: Find time from horizontal motion

Since horizontal velocity is constant:

Step 3: Use vertical motion equation

Substituting known values:

Verification:

Let’s verify this answer:

Discussion

The initial speed of 18.2 m/s (about 65 km/h or 40 mph) is reasonable for a strong soccer kick. The 40° launch angle is quite steep, which explains why the ball just barely clears the 2.4 m height at a horizontal distance of 30 m.

If the angle were lower, the ball would need a higher initial speed to reach the same height at that distance. Conversely, if the angle were higher (closer to 45°), the ball might go over the goal entirely or require a lower initial speed.

Answer

The initial speed of the ball must be 18.2 m/s (approximately 65 km/h or 40 mph).

Can a goalkeeper at their goal kick a soccer ball into the opponent’s goal without the ball touching the ground? The distance will be about 95 m. A goalkeeper can give the ball a speed of 30 m/s.

Strategy

Calculate the maximum range achievable with an initial speed of 30 m/s. Maximum range occurs at a 45° launch angle. Compare this to the required distance of 95 m.

Solution

Given:

Calculate maximum range:

At 45°, $\sin(2 \times 45°) = \sin(90°) = 1$, so the range equation simplifies to:

Rounding to two significant figures: R = 92 m

Discussion

The maximum range of 92 m is less than the required 95 m, so the goalkeeper cannot kick the ball into the opponent’s goal without it touching the ground.

The goalkeeper falls short by:

To reach 95 m, the goalkeeper would need an initial speed of:

So the goalkeeper would need to kick just 0.5 m/s faster (about 2% harder) to reach the opponent’s goal.

In reality, air resistance would reduce the actual range significantly below the calculated 92 m. A typical soccer ball experiences substantial air drag, which could reduce the range by 20-30% or more. This makes the feat even more impossible under real conditions.

Additionally, regulations and field dimensions vary, but a typical soccer field is 90-120 m long, so 95 m represents kicking almost the full length of the field.

Answer

No, the goalkeeper cannot kick the ball into the opponent’s goal. The maximum range with a 30 m/s kick is approximately 92 m, which is 3 m short of the required 95 m distance.

The free throw line in basketball is 4.57 m (15 ft) from the basket, which is 3.05 m (10 ft) above the floor. A player standing on the free throw line throws the ball with an initial speed of 8.15 m/s, releasing it at a height of 2.44 m (8 ft) above the floor. At what angle above the horizontal must the ball be thrown to exactly hit the basket? Note that most players will use a large initial angle rather than a flat shot because it allows for a larger margin of error. Explicitly show how you follow the steps involved in solving projectile motion problems.

Strategy

Follow the standard projectile motion problem-solving steps: identify knowns and unknowns, set up coordinate system, break into horizontal and vertical components, apply kinematic equations, and solve for the unknown angle.

Solution

Step 1: Identify knowns and unknowns

Knowns:

Unknown:

Step 2: Set up coordinate system

Origin at release point, x-axis horizontal (toward basket), y-axis vertical (up is positive).

Step 3: Break motion into components

Horizontal component (constant velocity):

Vertical component (constant acceleration):

Step 4: Apply kinematic equations

Horizontal motion:

Solving for time:

Vertical motion:

Step 5: Substitute and solve for θ

Substitute the expression for t from horizontal motion:

Using $\sec^2\theta = 1 + \tan^2\theta$, so $\frac{1}{\cos^2\theta} = 1 + \tan^2\theta$:

Using the quadratic formula with $u = \tan\theta$:

Two solutions:

Discussion

There are two possible angles: 30.3° (flatter trajectory) and 67.2° (higher arc). Players typically use the larger angle (around 50-55° in practice) because:

The 67.2° angle is closer to the preferred technique, though in practice, players often use angles around 50-55°.

Answer

The ball can be thrown at either 30.3° or 67.2° above horizontal. Most players use the larger angle because it allows for a larger margin of error and a better chance of the ball going in even if it hits the rim.

In 2007, Michael Carter (U.S.) set a world record in the shot put with a throw of 24.77 m. What was the initial speed of the shot if he released it at a height of 2.10 m and threw it at an angle of $38.0^\circ$ above the horizontal? (Although the maximum distance for a projectile on level ground is achieved at $45^\circ$ when air resistance is neglected, the actual angle to achieve maximum range is smaller; thus, $38^\circ$ will give a longer range than $45^\circ$ in the shot put.)

Strategy

Since the shot is released above ground level and lands on the ground, we cannot use the simple range equation. Instead, use the projectile motion equations with the release height of 2.10 m and landing height of 0 m.

Solution

Given:

Step 1: Express velocity components

Step 2: Find time from horizontal motion

Step 3: Apply vertical motion equation

At landing, $y = 0$:

Discussion

The initial speed of 15.0 m/s is reasonable for a world-class shot putter. This is about 54 km/h or 34 mph, which represents tremendous power given that the men’s shot weighs 7.26 kg (16 pounds).

The 38° release angle is optimal for shot put because:

In practice, elite shot putters release between 35-40°, confirming that 38° is near optimal.

Answer

The initial speed of the shot was 15.0 m/s (approximately 54 km/h or 34 mph).

A basketball player is running at $5.00 \ms$ directly toward the basket when he jumps into the air to dunk the ball. He maintains his horizontal velocity. (a) What vertical velocity does he need to rise 0.750 m above the floor? (b) How far from the basket (measured in the horizontal direction) must he start his jump to reach his maximum height at the same time as he reaches the basket?

Strategy

For part (a), use the kinematic equation relating velocity and displacement for vertical motion. For part (b), find the time to reach maximum height, then use horizontal motion to find the starting distance.

Solution

Given:

(a) Vertical velocity needed:

At maximum height, the vertical velocity is zero. Using:

At the top, $v_y = 0$:

(b) Starting distance from basket:

First, find the time to reach maximum height:

At maximum height, $v_y = 0$:

Horizontal distance traveled during this time:

Discussion

The player needs to jump with an upward velocity of 3.83 m/s to rise 0.750 m. This is a reasonable vertical jump velocity for an athlete.

The player must start the jump about 2.0 m from the basket. This timing is crucial for a successful dunk:

The calculation assumes the player maintains exactly 5.00 m/s horizontal velocity during the jump, which is reasonable for skilled athletes. The total jump time would be about 0.78 s (up and down), during which the player travels about 3.9 m horizontally.

Answer

(a) The player needs a vertical velocity of 3.83 m/s to rise 0.750 m.

(b) The player must start the jump 1.96 m (approximately 2.0 m) from the basket.

A football player punts the ball at a $45.0^\circ$ angle. Without an effect from the wind, the ball would travel 60.0 m horizontally. (a) What is the initial speed of the ball? (b) When the ball is near its maximum height it experiences a brief gust of wind that reduces its horizontal velocity by 1.50 m/s. What distance does the ball travel horizontally?

Strategy

For part (a), use the range equation to find the initial speed. For part (b), find the time to maximum height, calculate distance before and after the wind gust, then sum them.

Solution

Given:

(a) Initial speed:

At 45°, $\sin(2 \times 45°) = \sin(90°) = 1$, so:

(b) Range with wind gust:

First, find the velocity components:

Time to reach maximum height:

Horizontal distance to maximum height:

After the wind gust, horizontal velocity becomes:

Time to fall from maximum height (by symmetry, same as time to rise):

Horizontal distance during descent:

Total horizontal distance:

Discussion

The initial speed of 24.2 m/s (about 87 km/h or 54 mph) is reasonable for a punted football. The 45° angle gives maximum range when air resistance is neglected.

The wind gust reduces the horizontal velocity from 17.1 m/s to 15.6 m/s (about a 9% reduction). This causes the ball to land about 2.6-3 m shorter than it would have without wind, reducing the range from 60.0 m to approximately 57 m.

The effect is relatively modest because:

In real football games, wind can have a much larger effect, especially on high, “hang-time” punts that stay airborne longer.

Answer

(a) The initial speed of the ball is 24.2 m/s.

(b) With the wind gust, the ball travels 57.4 m horizontally (a reduction of about 2.6 m from the original 60.0 m).

Prove that the trajectory of a projectile is parabolic, having the form $y=a x +b x^{2}$. To obtain this expression, solve the equation $x=v_{0x}t$ for $t$ and substitute it into the expression for $y=v_{0y}t-\left(1/2\right)g t^{2}$ (These equations describe the $x$ and $y$ positions of a projectile that starts at the origin.) You should obtain an equation of the form $y=a x+b x^{2}$ where $a$ and $b$ are constants.

Strategy

Start with the parametric equations for projectile motion (x and y as functions of time), eliminate time by solving for t from the x-equation, then substitute into the y-equation to get y as a function of x.

Solution

Given equations:

Step 1: Solve for t from the x-equation:

Step 2: Substitute into the y-equation:

Step 3: Simplify:

Step 4: Identify constants:

This is in the form $y = ax + bx^2$ where:

Since $v*{0x} = v_0\cos\theta_0$ and $v*{0y} = v_0\sin\theta_0$:

Discussion

This equation has the form $y = ax + bx^2$, which is a parabola. The coefficient $a$ represents the initial slope (tangent of launch angle), while $b$ is always negative (since g is positive), causing the parabola to open downward. This mathematical form confirms what we observe: projectiles follow parabolic paths. The shape depends on initial velocity and launch angle—shallow angles give wide, flat parabolas; steep angles give narrow, tall parabolas.

Answer

The trajectory equation $y = \frac{v*{0y}}{v*{0x}}x - \frac{g}{2v\_{0x}^2}x^2$ is in the form y = ax + bx², proving that projectile motion follows a parabolic path.

Derive $R=\frac{ v_{0}^{2}\sin{2\theta }_{0}}{g}$ for the range of a projectile on level ground by finding the time $t$ at which $y$ becomes zero and substituting this value of $t$ into the expression for $x-x_{0}$, noting that $R=x-x_{0}$

$y-y_{0}=0=v_{0y}t-\frac{1}{2}g t^{2}=\left(v_{0}\sin{\theta} \right) t-\frac{1}{2}gt^{2}$, so that $t=\frac{2\left(v_{0}\sin{\theta}\right)}{g}$ $x-x_{0}=v_{0x}t=\left(v_{0}\cos{\theta}\right)t=R,$ and substituting for $t$ gives:

$R=v_{0}\cos{\theta} \left(\frac{ 2 v_{0}\sin{\theta}}{g}\right)=\frac{ 2v_ {0}^{2}\sin{\theta} \cos{\theta} }{g}$ since $2\sin{\theta} \cos{\theta} =\sin{2\theta}$, the range is:

Unreasonable Results

(a) Find the maximum range of a super cannon that has a muzzle velocity of 4.0 km/s. (b) What is unreasonable about the range you found? (c) Is the premise unreasonable or is the available equation inapplicable? Explain your answer. (d) If such a muzzle velocity could be obtained, discuss the effects of air resistance, thinning air with altitude, and the curvature of the Earth on the range of the super cannon.

Strategy

Use the range formula for projectile motion, then analyze whether the result is physically reasonable. Consider factors like Earth’s curvature, atmosphere, and the validity of the projectile motion equations.

Solution

(a) Maximum range:

The range formula is:

Maximum range occurs at $\theta_0 = 45°$, where $\sin(2\theta_0) = \sin(90°) = 1$:

Given: $v_0 = 4.0 \text{ km/s} = 4000 \ms$, $g = 9.80 \mss$

(b) What is unreasonable:

The range of 1630 km is unreasonable for several reasons:

(c) Is the premise or equation inappropriate:

Both are problematic:

(d) Effects if such velocity were obtained:

Discussion

This problem illustrates the limits of simple projectile motion models. The equations $R = \frac{v_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{g}$ work well for everyday projectiles (balls, arrows, bullets) but break down for extreme velocities and ranges. At 4 km/s, we need orbital mechanics, not projectile motion. The calculated range ignores that the projectile would actually enter a suborbital trajectory.

Answer

(a) The calculated maximum range is 1630 km (or 1.63 × 10³ km).

(b) This range is unreasonable because it ignores Earth’s curvature, atmospheric effects, and the fact that the projectile approaches orbital velocity.

(c) The equation is inapplicable at this scale—orbital mechanics, not projectile motion, governs such high-speed trajectories.

(d) Air resistance would cause intense heating and deceleration; the thinning atmosphere would reduce drag at altitude; Earth’s curvature would cause the projectile to follow an orbital path rather than a parabolic trajectory.

Construct Your Own Problem

Consider a ball tossed over a fence. Construct a problem in which you calculate the ball’s needed initial velocity to just clear the fence. Among the things to determine are; the height of the fence, the distance to the fence from the point of release of the ball, and the height at which the ball is released. You should also consider whether it is possible to choose the initial speed for the ball and just calculate the angle at which it is thrown. Also examine the possibility of multiple solutions given the distances and heights you have chosen.

Strategy

Design a realistic scenario with specific values for fence height, distance, and release height. Then demonstrate the solution process, including checking for multiple solutions and discussing the physics involved.

Solution

Problem Construction:

A baseball player throws a ball to clear a 3.0 m high fence. The fence is 20.0 m away horizontally, and the ball is released from a height of 2.0 m.

Given values:

Approach: Choose an initial speed (say $v_0 = 15.0 \ms$) and find the launch angle(s) needed.

Trajectory equation:

At the fence ($x = 20.0 \m$, $y - y_0 = 1.0 \m$):

Using $\sec^2\theta = 1 + \tan^2\theta$:

Using quadratic formula with $a = 8.71$, $b = -20.0$, $c = 9.71$:

Two solutions:

Discussion

This problem demonstrates several key concepts:

Multiple solutions: Most projectile problems have two launch angles that work—one steep ($58.0°$), one shallow ($34.8°$). Both clear the fence at exactly 3.0 m.

Choosing vs. calculating: We chose $v_0 = 15.0 \ms$ and calculated angles. Alternatively, we could choose an angle and calculate the required speed. However, we cannot independently choose both—they’re constrained by the trajectory equation.

Minimum speed: There exists a minimum initial speed below which no angle works. This occurs when the discriminant equals zero: $v_0^{\text{min}} = \sqrt{\frac{gx_f^2}{2(x_f\sin(2\alpha) - \Delta y\cos^2\alpha)}}$ where $\alpha = 45°$ gives the minimum.

Physical reasonableness: Both angles are realistic for throwing. The steeper angle gives a higher, shorter trajectory; the shallower angle gives a longer, flatter trajectory.

Answer

For a ball released at 2.0 m height to clear a 3.0 m fence 20.0 m away with initial speed 15.0 m/s, two launch angles work: 58.0° (steep) or 34.8° (shallow). This demonstrates that projectile problems often have two solutions—one high arc, one low arc—both reaching the same point.

$$