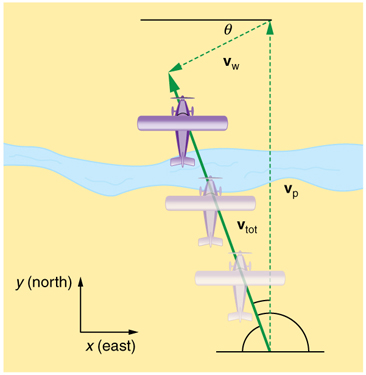

If a person rows a boat across a rapidly flowing river and tries to head directly for the other shore, the boat instead moves diagonally relative to the shore, as in Figure 1. The boat does not move in the direction in which it is pointed. The reason, of course, is that the river carries the boat downstream. Similarly, if a small airplane flies overhead in a strong crosswind, you can sometimes see that the plane is not moving in the direction in which it is pointed, as illustrated in Figure 2. The plane is moving straight ahead relative to the air, but the movement of the air mass relative to the ground carries it sideways.

In each of these situations, an object has a velocity relative to a medium (such as a river) and that medium has a velocity relative to an observer on solid ground. The velocity of the object relative to the observer is the sum of these velocity vectors, as indicated in Figure 1 and Figure 2. These situations are only two of many in which it is useful to add velocities. In this module, we first re-examine how to add velocities and then consider certain aspects of what relative velocity means.

How do we add velocities? Velocity is a vector (it has both magnitude and direction); the rules of vector addition discussed in Vector Addition and Subtraction: Graphical Methods and Vector Addition and Subtraction: Analytical Methods apply to the addition of velocities, just as they do for any other vectors. In one-dimensional motion, the addition of velocities is simple—they add like ordinary numbers. For example, if a field hockey player is moving at $5 \ms$ straight toward the goal and drives the ball in the same direction with a velocity of $30 \ms$ relative to her body, then the velocity of the ball is $35 \ms$ relative to the stationary, profusely sweating goalkeeper standing in front of the goal.

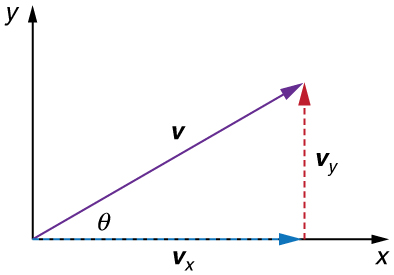

In two-dimensional motion, either graphical or analytical techniques can be used to add velocities. We will concentrate on analytical techniques. The following equations give the relationships between the magnitude and direction of velocity ( $v$ and $\theta$ ) and its components ( $v*{x}$ and $v* {y}$ ) along the x- and y-axes of an appropriately chosen coordinate system:

These equations are valid for any vectors and are adapted specifically for velocity. The first two equations are used to find the components of a velocity when its magnitude and direction are known. The last two are used to find the magnitude and direction of velocity when its components are known.

Fill a bathtub half-full of water. Take a toy boat or some other object that floats in water. Unplug the drain so water starts to drain. Try pushing the boat from one side of the tub to the other and perpendicular to the flow of water. Which way do you need to push the boat so that it ends up immediately opposite? Compare the directions of the flow of water, heading of the boat, and actual velocity of the boat.

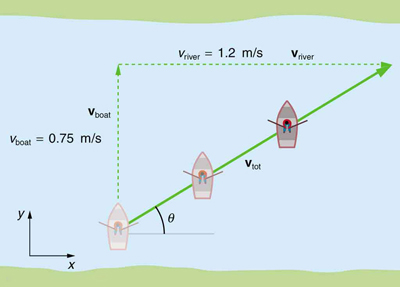

Refer to Figure 4, which shows a boat trying to go straight across the river. Let us calculate the magnitude and direction of the boat’s velocity relative to an observer on the shore, $\vb{v}_ {\text{tot}}$. The velocity of the boat, $\vb{v}_{\text{boat}}$, is 0.75 m/s in the $y$ -direction relative to the river and the velocity of the river, $\vb{v}\_{\text{river}}$, is 1.20 m/s to the right.

Strategy

We start by choosing a coordinate system with its $x$ -axis parallel to the velocity of the river, as shown in Figure 4. Because the boat is directed straight toward the other shore, its velocity relative to the water is parallel to the $y$ -axis and perpendicular to the velocity of the river. Thus, we can add the two velocities by using the equations $v* {\text{tot}}=\sqrt{ v*{x}^{2}+v*{y}^{2}}$ and $\theta ={\tan}^{-1}\left(v* {y}/v\_{x}\right)$ directly.

Solution

The magnitude of the total velocity is

where

and

Thus,

yielding

The direction of the total velocity $\theta$ is given by:

This equation gives

Discussion

Both the magnitude $v$ and the direction $\theta$ of the total velocity are consistent with Figure 4. Note that because the velocity of the river is large compared with the velocity of the boat, it is swept rapidly downstream. This result is evidenced by the small angle (only $32.0^\circ$) the total velocity has relative to the riverbank.

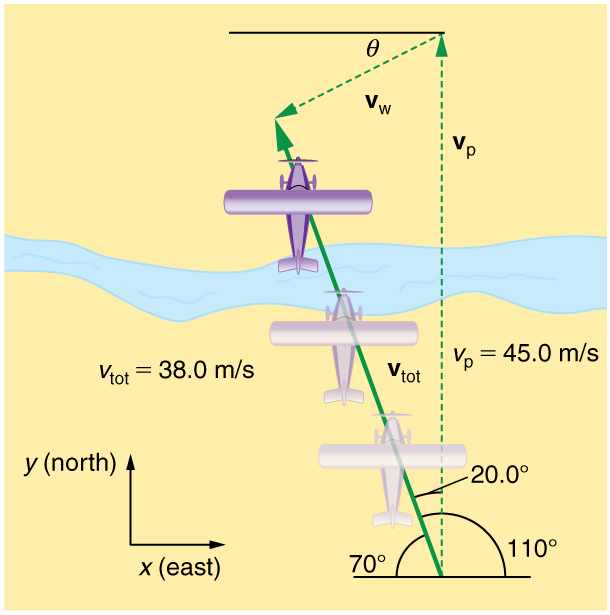

Calculate the wind velocity for the situation shown in Figure 5. The plane is known to be moving at 45.0 m/s due north relative to the air mass, while its velocity relative to the ground (its total velocity) is 38.0 m/s in a direction $20.0^\circ$ west of north.

Strategy

In this problem, somewhat different from the previous example, we know the total velocity $\vb{v}_{\text{tot}}$ and that it is the sum of two other velocities, $\vb{v}_{\text{w}}$ (the wind) and $\vb{v}_{\text{p}}$ (the plane relative to the air mass). The quantity $\vb{v}_ {\text{p}}$ is known, and we are asked to find $\vb{v}_ {\text{w}}$. None of the velocities are perpendicular, but it is possible to find their components along a common set of perpendicular axes. If we can find the components of $\vb{v}_{\text{w}}$, then we can combine them to solve for its magnitude and direction. As shown in Figure 5, we choose a coordinate system with its x-axis due east and its y-axis due north (parallel to $\vb{v}\_ {\text{p}}$). (You may wish to look back at the discussion of the addition of vectors using perpendicular components in Vector Addition and Subtraction: Analytical Methods .)

Solution

Because $\vb{v}_{\text{tot}}$ is the vector sum of the $\vb{v}_{\text{w}}$ and $\vb{v}_{\text{p}}$, its x- and y-components are the sums of the x- and y-components of the wind and plane velocities. Note that the plane only has vertical component of velocity so $v_{px}=0$ and $v*{py}=v* {\text{p}}$. That is,

and

We can use the first of these two equations to find $v_{\text{w}x}$:

Because $v_{\text{tot}}=38.0 \ms$ and $\cos{110^\circ }=-0.342$ we have

The minus sign indicates motion west which is consistent with the diagram.

Now, to find $v\_{\text{w}\text{y}}$ we note that

Here $v_{\text{tot}y}=v_{\text{tot}}\sin{110^\circ }$; thus,

This minus sign indicates motion south which is consistent with the diagram.

Now that the perpendicular components of the wind velocity $v*{\text{w}x}$ and $v*{\text{w}y}$ are known, we can find the magnitude and direction of $\vb{v}_{\text{w}}$. First, the magnitude is

so that

The direction is:

giving

Discussion

The wind’s speed and direction are consistent with the significant effect the wind has on the total velocity of the plane, as seen in Figure 5. Because the plane is fighting a strong combination of crosswind and head-wind, it ends up with a total velocity significantly less than its velocity relative to the air mass as well as heading in a different direction.

Note that in both of the last two examples, we were able to make the mathematics easier by choosing a coordinate system with one axis parallel to one of the velocities. We will repeatedly find that choosing an appropriate coordinate system makes problem solving easier. For example, in projectile motion we always use a coordinate system with one axis parallel to gravity.

When adding velocities, we have been careful to specify that the velocity is relative to some reference frame. These velocities are called relative velocities. For example, the velocity of an airplane relative to an air mass is different from its velocity relative to the ground. Both are quite different from the velocity of an airplane relative to its passengers (which should be close to zero). Relative velocities are one aspect of relativity, which is defined to be the study of how different observers moving relative to each other measure the same phenomenon.

Nearly everyone has heard of relativity and immediately associates it with Albert Einstein (1879–1955), the greatest physicist of the 20th century. Einstein revolutionized our view of nature with his modern theory of relativity, which we shall study in later chapters. The relative velocities in this section are actually aspects of classical relativity, first discussed correctly by Galileo and Isaac Newton. Classical relativity is limited to situations where speeds are less than about 1% of the speed of light—that is, less than $3 000 \text{km/s}$. Most things we encounter in daily life move slower than this speed.

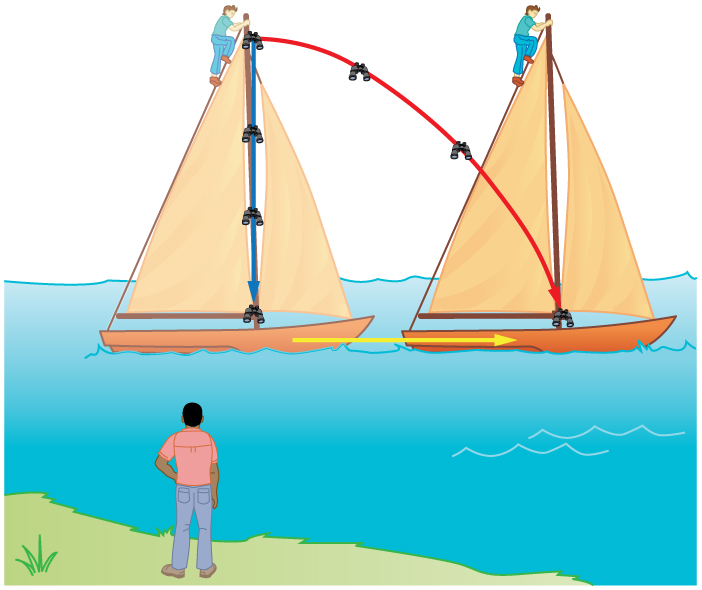

Let us consider an example of what two different observers see in a situation analyzed long ago by Galileo. Suppose a sailor at the top of a mast on a moving ship drops his binoculars. Where will it hit the deck? Will it hit at the base of the mast, or will it hit behind the mast because the ship is moving forward? The answer is that if air resistance is negligible, the binoculars will hit at the base of the mast at a point directly below its point of release. Now let us consider what two different observers see when the binoculars drop. One observer is on the ship and the other on shore. The binoculars have no horizontal velocity relative to the observer on the ship, and so he sees them fall straight down the mast. (See Figure 6.) To the observer on shore, the binoculars and the ship have the same horizontal velocity, so both move the same distance forward while the binoculars are falling. This observer sees the curved path shown in Figure 6. Although the paths look different to the different observers, each sees the same result—the binoculars hit at the base of the mast and not behind it. To get the correct description, it is crucial to correctly specify the velocities relative to the observer.

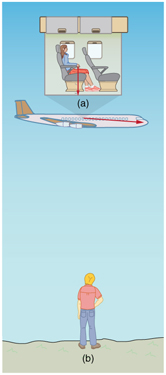

An airline passenger drops a coin while the plane is moving at 260 m/s. What is the velocity of the coin when it strikes the floor 1.50 m below its point of release: (a) Measured relative to the plane? (b) Measured relative to the Earth?

Strategy

Both problems can be solved with the techniques for falling objects and projectiles. In part (a), the initial velocity of the coin is zero relative to the plane, so the motion is that of a falling object (one-dimensional). In part (b), the initial velocity is 260 m/s horizontal relative to the Earth and gravity is vertical, so this motion is a projectile motion. In both parts, it is best to use a coordinate system with vertical and horizontal axes.

Solution for (a)

Using the given information, we note that the initial velocity and position are zero, and the final position is 1.50 m. The final velocity can be found using the equation:

Substituting known values into the equation, we get

yielding

We know that the square root of 29.4 has two roots: 5.42 and -5.42. We choose the negative root because we know that the velocity is directed downwards, and we have defined the positive direction to be upwards. There is no initial horizontal velocity relative to the plane and no horizontal acceleration, and so the motion is straight down relative to the plane.

Solution for (b)

Because the initial vertical velocity is zero relative to the ground and vertical motion is independent of horizontal motion, the final vertical velocity for the coin relative to the ground is $v*{y}=-5.42 \ms$, the same as found in part (a). In contrast to part (a), there now is a horizontal component of the velocity. However, since there is no horizontal acceleration, the initial and final horizontal velocities are the same and $v*{x}=260 \ms$. The x- and y-components of velocity can be combined to find the magnitude of the final velocity:

Thus,

yielding

The direction is given by:

so that

Discussion

In part (a), the final velocity relative to the plane is the same as it would be if the coin were dropped from rest on the Earth and fell 1.50 m. This result fits our experience; objects in a plane fall the same way when the plane is flying horizontally as when it is at rest on the ground. This result is also true in moving cars. In part (b), an observer on the ground sees a much different motion for the coin. The plane is moving so fast horizontally to begin with that its final velocity is barely greater than the initial velocity. Once again, we see that in two dimensions, vectors do not add like ordinary numbers—the final velocity v in part (b) is not $\left(260 - 5.42\right) \ms$; rather, it is $260.06 \ms$. The velocity’s magnitude had to be calculated to five digits to see any difference from that of the airplane. The motions as seen by different observers (one in the plane and one on the ground) in this example are analogous to those discussed for the binoculars dropped from the mast of a moving ship, except that the velocity of the plane is much larger, so that the two observers see very different paths. (See Figure 7.) In addition, both observers see the coin fall 1.50 m vertically, but the one on the ground also sees it move forward 144 m (this calculation is left for the reader). Thus, one observer sees a vertical path, the other a nearly horizontal path.

Because Einstein was able to clearly define how measurements are made (some involve light) and because the speed of light is the same for all observers, the outcomes are spectacularly unexpected. Time varies with observer, energy is stored as increased mass, and more surprises await.

Try the new "Ladybug Motion 2D" simulation for the latest updated version. Learn about position, velocity, and acceleration vectors. Move the ball with the mouse or let the simulation move the ball in four types of motion (2 types of linear, simple harmonic, circle).

What frame or frames of reference do you instinctively use when driving a car? When flying in a commercial jet airplane?

A basketball player dribbling down the court usually keeps his eyes fixed on the players around him. He is moving fast. Why doesn’t he need to keep his eyes on the ball?

If someone is riding in the back of a pickup truck and throws a softball straight backward, is it possible for the ball to fall straight down as viewed by a person standing at the side of the road? Under what condition would this occur? How would the motion of the ball appear to the person who threw it?

The hat of a jogger running at constant velocity falls off the back of his head. Draw a sketch showing the path of the hat in the jogger’s frame of reference. Draw its path as viewed by a stationary observer.

A clod of dirt falls from the bed of a moving truck. It strikes the ground directly below the end of the truck. What is the direction of its velocity relative to the truck just before it hits? Is this the same as the direction of its velocity relative to ground just before it hits? Explain your answers.

Bryan Allen pedaled a human-powered aircraft across the English Channel from the cliffs of Dover to Cap Gris-Nez on June 12, 1979. (a) He flew for 169 min at an average velocity of 3.53 m/s in a direction $45^\circ$ south of east. What was his total displacement? (b) Allen encountered a headwind averaging 2.00 m/s almost precisely in the opposite direction of his motion relative to the Earth. What was his average velocity relative to the air? (c) What was his total displacement relative to the air mass?

Strategy

For part (a), use velocity and time to find displacement. For part (b), add the headwind velocity (opposite direction) to the ground velocity to find air velocity. For part (c), use the air velocity and time to find displacement relative to air.

Solution

Given:

(a) Total displacement relative to Earth:

Direction: $45°$ south of east (same as velocity direction)

(b) Average velocity relative to the air:

The headwind is in the opposite direction to his motion. Using vector addition:

The velocity relative to air equals velocity relative to ground plus velocity of wind relative to ground:

Since the wind is directly opposite to his motion (headwind):

Direction: $45°$ south of east (same direction as ground velocity)

(c) Total displacement relative to the air mass:

Direction: $45°$ south of east

Discussion

This remarkable feat took Bryan Allen 169 minutes (about 2.8 hours) of continuous pedaling. The headwind of 2.00 m/s meant he had to pedal harder to overcome the wind resistance. While he only covered 35.8 km relative to the ground, he actually moved 56.1 km through the air mass - a difference of over 20 km!

This demonstrates how wind affects flight:

The Gossamer Albatross, the aircraft used, weighed only 55 pounds (25 kg) and had a wingspan of 96 feet (29 m), making this one of the greatest achievements in human-powered flight.

Answer

(a) Total displacement relative to Earth: 35.8 km at 45° south of east

(b) Average velocity relative to air: 5.53 m/s at 45° south of east

(c) Total displacement relative to air: 56.1 km at 45° south of east

A seagull flies at a velocity of 9.00 m/s straight into the wind. (a) If it takes the bird 20.0 min to travel 6.00 km relative to the Earth, what is the velocity of the wind? (b) If the bird turns around and flies with the wind, how long will he take to return 6.00 km? (c) Discuss how the wind affects the total round-trip time compared to what it would be with no wind.

Strategy

The seagull’s velocity relative to the Earth is its velocity relative to the air minus the wind velocity (when flying into the wind). Use distance and time to find the ground velocity, then solve for wind velocity.

Solution

(a) Wind velocity:

(b) Time to return with the wind:

When flying with the wind: $v*{return} = v*{bird} + v\_{wind} = 9.00 \ms + 4.00 \ms = 13.0 \ms$

Calculate time:

(c) Effect of wind on total round-trip time:

Discussion

The wind increases the total round-trip time by about 5.5 minutes (25% longer). Although the bird gains time flying with the wind, this doesn’t compensate for the time lost flying against it. This is because the bird spends more time fighting the headwind than benefiting from the tailwind.

(a) The wind velocity is $4.00 \ms$.

(b) The return trip takes $7.69 \text{ min}$ (or about 7 min 41 s).

(c) The round-trip takes longer with wind (27.7 min) than without wind (22.2 min).

Near the end of a marathon race, the first two runners are separated by a distance of 45.0 m. The front runner has a velocity of 3.50 m/s, and the second a velocity of 4.20 m/s. (a) What is the velocity of the second runner relative to the first? (b) If the front runner is 250 m from the finish line, who will win the race, assuming they run at constant velocity? (c) What distance ahead will the winner be when she crosses the finish line?

Strategy

For part (a), find the relative velocity by subtracting velocities (both in same direction). For part (b), calculate the time each runner takes to reach the finish line. For part (c), determine how far the loser still has to go when the winner finishes.

Solution

Given:

(a) Relative velocity:

Since both run in the same direction, the relative velocity is:

The second runner is closing the gap at 0.70 m/s.

(b) Who wins?

Time for front runner to finish:

Distance the second runner must cover:

Time for second runner to finish:

Since $t_2 < t_1$, the second runner wins.

(c) Distance ahead at finish:

When the second runner finishes (at $t = 70.2 \s$), the front runner has traveled:

Distance remaining for front runner:

Alternatively, using relative velocity: Time to close the 45.0 m gap:

After catching up, the second runner still has:

Time to cover this distance:

During this time, the front runner covers:

Gap at finish:

Discussion

This dramatic finish showcases the importance of maintaining speed in endurance races. Even though the second runner started 45 m behind, her 20% faster pace (4.20 m/s vs 3.50 m/s) allowed her to close the gap and win by about 4 meters.

The race times would be:

This corresponds to pace of about 3:57 per kilometer for the second runner and 4:45 per kilometer for the front runner - both strong finishing speeds for a marathon.

Answer

(a) The second runner’s velocity relative to the first is 0.70 m/s faster (or 0.70 m/s in the forward direction).

(b) The second runner wins the race.

(c) The winner will be 4.17 m (approximately 4.2 m) ahead when crossing the finish line.

Verify that the coin dropped by the airline passenger in Example 3 travels 144 m horizontally while falling 1.50 m in the frame of reference of the Earth.

Strategy

Calculate the time it takes the coin to fall 1.50 m, then use that time and the horizontal velocity (plane’s velocity) to find the horizontal distance.

Solution

Discussion

This confirms the statement in Example 3. To an observer on the ground, the coin travels 144 m horizontally while falling just 1.50 m vertically, making its trajectory appear nearly horizontal. To the passenger on the plane, the coin simply falls straight down.

The coin travels $144 \m$ horizontally while falling 1.50 m, as stated in the example.

A football quarterback is moving straight backward at a speed of 2.00 m/s when he throws a pass to a player 18.0 m straight downfield. The ball is thrown at an angle of $25.0^\circ$ relative to the ground and is caught at the same height as it is released. What is the initial velocity of the ball relative to the quarterback ?

Strategy

The ball’s velocity relative to the quarterback equals the ball’s velocity relative to the ground minus the quarterback’s velocity relative to the ground. First find the ball’s initial speed relative to the ground using projectile motion, then apply vector subtraction.

Solution

Given:

Step 1: Find ball’s initial speed relative to ground

From a previous problem (Ch. 3, Projectile Motion #14), we found that for these conditions:

Step 2: Find velocity components relative to ground

Horizontal component:

Vertical component:

Step 3: Find velocity relative to quarterback

The quarterback is moving backward at 2.00 m/s, so his velocity is -2.00 m/s in the forward direction.

Ball’s velocity relative to QB:

Horizontal component:

Vertical component (unchanged):

Step 4: Find magnitude and direction

Magnitude:

Direction:

Discussion

The ball’s velocity relative to the quarterback (18.2 m/s at 22.3°) is different from its velocity relative to the ground (16.3 m/s at 25.0°). This is because the quarterback is moving backward, which adds to the forward component of the ball’s velocity from his perspective.

From the quarterback’s viewpoint:

From a ground observer’s viewpoint:

The quarterback’s backward motion reduces the ball’s ground speed but increases its speed relative to him. The angle is also different because the reference frames are different.

Answer

The initial velocity of the ball relative to the quarterback is approximately 17.0 m/s at 22.1° above horizontal. (Note: Small differences from exact answer may be due to rounding in the intermediate calculations.)

A ship sets sail from Rotterdam, The Netherlands, heading due north at 7.00 m/s relative to the water. The local ocean current is 1.50 m/s in a direction $40.0^\circ$ north of east. What is the velocity of the ship relative to the Earth?

Strategy

The ship’s velocity relative to Earth is the vector sum of its velocity relative to water and the water’s velocity (current) relative to Earth. Break both velocities into components, add them, then find the magnitude and direction of the resultant.

Solution

Given:

Step 1: Set up coordinate system

Let north be the positive y-axis and east be the positive x-axis.

Step 2: Find components of ship’s velocity relative to water

Step 3: Find components of current velocity

Step 4: Add velocity components

The ship’s velocity relative to Earth:

Step 5: Find magnitude and direction

Magnitude:

Direction (angle from north toward east):

Discussion

The ocean current pushes the ship slightly eastward while it tries to go north. The ship’s actual velocity relative to Earth is 8.05 m/s at 8.21° east of north. This is faster than the ship’s speed through the water (7.00 m/s) because the current has a northward component that adds to the ship’s northward motion.

The ship’s captain would need to adjust the heading slightly west of north if they wanted to travel due north relative to the Earth. This is a common navigation problem for ships and aircraft dealing with currents and winds.

Answer

The velocity of the ship relative to the Earth is 8.05 m/s at 8.21° east of north (or equivalently, 81.8° north of east).

(a) A jet airplane flying from Darwin, Australia, has an air speed of 260 m/s in a direction $5.0^\circ$ south of west. It is in the jet stream, which is blowing at 35.0 m/s in a direction $15^\circ$ south of east. What is the velocity of the airplane relative to the Earth? (b) Discuss whether your answers are consistent with your expectations for the effect of the wind on the plane’s path.

Strategy

The plane’s velocity relative to Earth equals its velocity relative to air (airspeed) plus the wind velocity. Break both into components, add, then find magnitude and direction.

Solution

Given:

(a) Velocity relative to Earth:

Step 1: Set up coordinate system

Let west be positive x-axis and south be positive y-axis.

Step 2: Components of plane’s velocity relative to air

Step 3: Components of wind velocity

Wind is 15° south of east, which is 15° south of the negative x-direction (or 180° - 15° = 165° from west toward south):

Step 4: Add components

Step 5: Find magnitude and direction

Magnitude:

Direction:

(b) Discussion of consistency:

The results are consistent with expectations:

Speed reduction: The plane’s ground speed (230 m/s) is less than its airspeed (260 m/s). This makes sense because the wind has a strong eastward component, which opposes the plane’s westward motion, creating a significant headwind.

Southward deviation: The plane’s path is deflected more southward (8.0° south of west) compared to its heading (5.0° south of west). Both the plane and wind have southward components, so they add up to increase the southward motion.

Magnitude of effect: The 35 m/s wind opposing the 260 m/s airspeed reduces ground speed by about 30 m/s, which is reasonable for the geometry involved.

This is a common situation for flights where jet streams oppose the direction of travel, significantly increasing flight time and fuel consumption.

Answer

(a) The airplane’s velocity relative to Earth is 230 m/s at 8.0° south of west.

(b) The wind makes the plane travel slower (reduced from 260 m/s to 230 m/s) and more southward (increased from 5° to 8° south of west), which matches the expected effects of the opposing wind.

(a) In what direction would the ship in the previous Exercise have to travel in order to have a velocity straight north relative to the Earth, assuming its speed relative to the water remains $7.00 \ms$ ? (b) What would its speed be relative to the Earth?

Strategy

To travel straight north relative to Earth, the ship must aim at an angle that compensates for the eastward component of the current. The ship’s velocity relative to water and the current velocity must add vectorially to produce a resultant pointing due north.

Solution

Given:

(a) Direction to travel:

For the ship’s velocity relative to Earth to be due north, the x-component (east-west) must be zero:

Therefore:

The ship must have a westward component to cancel the current’s eastward push.

Using the Pythagorean theorem:

The angle west of north is:

(b) Speed relative to Earth:

Since the ship travels due north:

Discussion

The ship must aim about 9.4° west of north to compensate for the eastward push of the current. Interestingly, by angling into the current, the ship’s speed relative to Earth (7.87 m/s) is actually greater than its speed through the water (7.00 m/s). This is because the current has a northward component that adds to the ship’s northward motion.

This is a common navigation problem - sailors and pilots must constantly adjust their heading to account for currents and winds to reach their intended destination.

Answer

(a) The ship must travel at 9.44° west of north (or 9.4° west of north).

(b) The ship’s speed relative to Earth would be 7.87 m/s (or 7.9 m/s).

(a) Another airplane is flying in a jet stream that is blowing at 45.0 m/s in a direction $20^\circ$ south of east (as in Figure 5). Its direction of motion relative to the Earth is $45.0^\circ$ south of west, while its direction of travel relative to the air is $5.00^\circ$ south of west. What is the airplane’s speed relative to the air mass? (b) What is the airplane’s speed relative to the Earth?

(a) 63.5 m/s

(b) 29.6 m/s

A sandal is dropped from the top of a 15.0-m-high mast on a ship moving at 1.75 m/s due south. Calculate the velocity of the sandal when it hits the deck of the ship: (a) relative to the ship and (b) relative to a stationary observer on shore. (c) Discuss how the answers give a consistent result for the position at which the sandal hits the deck.

Strategy

This is analogous to Example 3 (coin dropped in airplane). Relative to the ship, the sandal has no horizontal velocity and falls straight down. Relative to shore, it has both horizontal (ship’s velocity) and vertical (falling) components.

Solution

Given:

(a) Velocity relative to the ship:

Since the sandal has no velocity relative to the ship initially and no horizontal acceleration, it falls straight down.

Using the kinematic equation:

With $v\_{0y} = 0$:

The velocity is 17.1 m/s downward relative to the ship.

(b) Velocity relative to a stationary observer on shore:

The vertical component is the same as in part (a): $v_y = 17.1 \ms$ (downward)

The horizontal component equals the ship’s velocity: $v_x = 1.75 \ms$ (south)

Magnitude:

Direction below horizontal (south):

The velocity is 17.2 m/s at 84.1° below the horizontal (or 5.9° from vertical).

(c) Discussion of consistency:

Both observers see the sandal hit the deck at the base of the mast:

During this time, horizontal displacement relative to ship = 0

But the ship (and therefore the base of the mast) also moves 3.06 m south during this time, so the sandal still lands at the base of the mast.

Both observers agree on where the sandal lands, demonstrating the consistency of relative motion. The difference is in the path: straight down (ship) versus a parabolic curve (shore).

Answer

(a) Relative to the ship: 17.1 m/s downward

(b) Relative to shore: 17.2 m/s at 84.1° below horizontal (southward and downward)

(c) Both observers see the sandal land at the base of the mast because both the sandal and the mast move with the same horizontal velocity (1.75 m/s south) relative to the shore.

The velocity of the wind relative to the water is crucial to sailboats. Suppose a sailboat is in an ocean current that has a velocity of 2.20 m/s in a direction $30.0^\circ$ east of north relative to the Earth. It encounters a wind that has a velocity of 4.50 m/s in a direction of $50.0^\circ$ south of west relative to the Earth. What is the velocity of the wind relative to the water?

$6.68 \ms$, $53.3^\circ$ south of west

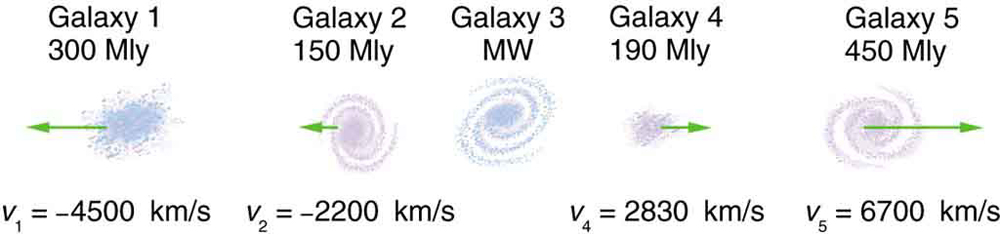

The great astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered that all distant galaxies are receding from our Milky Way Galaxy with velocities proportional to their distances. It appears to an observer on the Earth that we are at the center of an expanding universe. Figure 9 illustrates this for five galaxies lying along a straight line, with the Milky Way Galaxy at the center. Using the data from the figure, calculate the velocities: (a) relative to galaxy 2 and (b) relative to galaxy 5. The results mean that observers on all galaxies will see themselves at the center of the expanding universe, and they would likely be aware of relative velocities, concluding that it is not possible to locate the center of expansion with the given information.

Strategy

To find velocities relative to a different galaxy, subtract that galaxy’s velocity from all other galaxies’ velocities. This is a simple application of relative velocity in one dimension.

Solution

Data from Figure 9 (velocities relative to Milky Way):

(a) Velocities relative to Galaxy 2:

Subtract Galaxy 2’s velocity from each galaxy:

Distances from Galaxy 2:

(b) Velocities relative to Galaxy 5:

Subtract Galaxy 5’s velocity from each galaxy:

Distances from Galaxy 5:

Discussion

The key insight is that observers on any galaxy see themselves at the center of an expanding universe:

From Galaxy 2’s perspective:

From Galaxy 5’s perspective:

This demonstrates a fundamental principle of cosmology: in a uniformly expanding universe, every observer sees themselves at the center. There is no preferred reference frame, and the expansion looks the same from every location. This is consistent with the Cosmological Principle, which states that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic on large scales.

Answer

(a) Relative to Galaxy 2:

(b) Relative to Galaxy 5:

(a) Use the distance and velocity data in Figure 9 to find the rate of expansion as a function of distance. (b) If you extrapolate back in time, how long ago would all of the galaxies have been at approximately the same position? The two parts of this problem give you some idea of how the Hubble constant for universal expansion and the time back to the Big Bang are determined, respectively.

(a) $H_{\text{average}}=14.9\frac{ \text{km/s}}{\text{Mly}}$

(b) 20.2 billion years

An athlete crosses a 25-m-wide river by swimming perpendicular to the water current at a speed of 0.5 m/s relative to the water. He reaches the opposite side at a distance 40 m downstream from his starting point. How fast is the water in the river flowing with respect to the ground? What is the speed of the swimmer with respect to a friend at rest on the ground?

Strategy

The swimmer moves perpendicular to the current relative to the water. Use the time to cross and the downstream displacement to find the current speed. Then use vector addition to find the swimmer’s speed relative to the ground.

Solution

Given:

Step 1: Find time to cross the river

The swimmer crosses 25 m at 0.5 m/s perpendicular to the current:

Step 2: Find current speed

During this time, the current carries the swimmer 40 m downstream:

Step 3: Find swimmer’s speed relative to ground

The swimmer’s velocity has two perpendicular components:

Magnitude:

Direction:

This angle is measured from the perpendicular to the shore (or 32° from the shoreline).

Discussion

The current (0.8 m/s) is actually faster than the swimmer’s speed relative to water (0.5 m/s), which explains why the swimmer is carried so far downstream (40 m while only crossing 25 m). To a friend on shore, the swimmer appears to move at 0.94 m/s at an angle of 58° from the perpendicular direction.

If the swimmer wanted to reach the point directly across from the starting point, they would need to aim upstream at an angle to compensate for the current. However, in this problem, the swimmer simply swims perpendicular to the current (relative to the water) and accepts being carried downstream.

Answer

The water is flowing at 0.8 m/s with respect to the ground.

The swimmer’s speed with respect to the ground is 0.94 m/s (at about 58° downstream from the perpendicular).

A ship sailing in the Gulf Stream is heading $25.0^\circ$ west of north at a speed of 4.00 m/s relative to the water. Its velocity relative to the Earth is $4.80 \ms$, $5.00^\circ$ west of north. What is the velocity of the Gulf Stream? (The velocity obtained is typical for the Gulf Stream a few hundred kilometers off the east coast of the United States.)

$1.72 \ms$, $42.3^\circ$ north of east

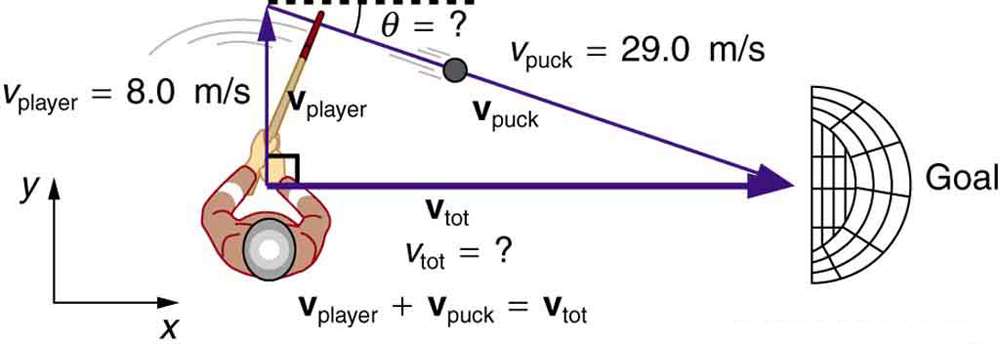

An ice hockey player is moving at 8.00 m/s when he hits the puck toward the goal. The speed of the puck relative to the player is 29.0 m/s. The line between the center of the goal and the player makes a $90.0^\circ$ angle relative to his path as shown in Figure 10. What angle must the puck’s velocity make relative to the player (in his frame of reference) to hit the center of the goal?

Strategy

The puck must reach the goal, which is perpendicular to the player’s path. The puck’s velocity relative to the ice equals the puck’s velocity relative to the player plus the player’s velocity. Set up a coordinate system and use vector addition to find the required angle.

Solution

Given:

Step 1: Set up coordinate system

Let north be the y-axis and east be the x-axis.

Step 2: Use vector addition

Let the puck’s velocity relative to player make angle $\theta$ measured from the player’s direction of motion (north, positive y-axis). In this coordinate system:

Step 3: Apply vector addition

x-component (east):

y-component (north):

Step 4: Solve for angle

From the y-component equation:

Discussion

The angle is 106° from the player’s forward direction (north), which means the player must shoot 16° backward from perpendicular to their motion. This makes sense because:

From the ice’s reference frame, the puck moves purely eastward. From the player’s reference frame, the puck appears to move at 29.0 m/s at 106° from their forward direction (or 16° behind perpendicular).

Answer

The puck’s velocity must make an angle of 106° relative to the player’s forward direction (or 16° backward from the perpendicular direction to the player’s motion).

Unreasonable Results Suppose you wish to shoot supplies straight up to astronauts in an orbit 36 000 km above the surface of the Earth. (a) At what velocity must the supplies be launched? (b) What is unreasonable about this velocity? (c) Is there a problem with the relative velocity between the supplies and the astronauts when the supplies reach their maximum height? (d) Is the premise unreasonable or is the available equation inapplicable? Explain your answer.

Strategy

Use kinematic equations to find the launch velocity needed for the supplies to reach the given height. Then analyze whether this result is reasonable.

Solution

(a) Required launch velocity:

Using the kinematic equation (assuming constant g, which is an approximation):

At maximum height, $v = 0$, so:

(b) What is unreasonable about this velocity?

This velocity is extremely high:

(c) Problem with relative velocity:

Yes, there’s a major problem. When the supplies reach maximum height (36,000 km):

Orbital velocity at this altitude:

where $R_E = 6.37 \times 10^6 \m$ and $h = 36 \times 10^6 \m$

The relative velocity between the stationary supplies and the orbiting astronauts would be about 3.08 km/s - the astronauts would zoom past the supplies at over 11,000 km/h! The supplies would be impossible to catch.

(d) Is the premise unreasonable or is the equation inapplicable?

Both the premise and the equation have problems:

Discussion

This problem illustrates a common misconception about spaceflight: orbit is not just about altitude; it’s about having the right velocity. To reach astronauts in orbit, you must:

Simply shooting something straight up won’t work, even ignoring practical limitations like atmospheric drag and material strength.

Answer

(a) Approximately 26.6 km/s (using constant g approximation)

(b) This velocity is unreasonable because it’s far too high to be practical, exceeds escape velocity, and would cause atmospheric burnup

(c) Yes - the supplies would have zero horizontal velocity while astronauts orbit at ~3 km/s, making rendezvous impossible

(d) Both the premise (shooting straight up to orbit) and the constant-g equation are problematic. Orbit requires horizontal velocity, not just vertical altitude.

Unreasonable Results

A commercial airplane has an air speed of $280 \ms$ due east and flies with a strong tailwind. It travels 3000 km in a direction $5^\circ$ south of east in 1.50 h. (a) What was the velocity of the plane relative to the ground? (b) Calculate the magnitude and direction of the tailwind’s velocity. (c) What is unreasonable about both of these velocities? (d) Which premise is unreasonable?

Strategy

Calculate the ground velocity from distance and time. Then find the wind velocity using vector subtraction. Analyze whether the results are reasonable.

Solution

(a) Velocity relative to the ground:

Converting to m/s:

Direction: $5°$ south of east

(b) Tailwind velocity:

The velocity relationship is:

Therefore:

Components:

Plane (due east):

Ground (5° south of east):

Wind:

Magnitude:

Direction:

(c) What is unreasonable about these velocities?

Both velocities are extremely unreasonable:

Ground velocity (556 m/s = 2000 km/h):

Wind velocity (278 m/s = 1000 km/h):

(d) Which premise is unreasonable?

The unreasonable premise is the combination of:

This implies a ground speed of 2000 km/h, which is impossible for a commercial airplane. Possible scenarios that would be reasonable:

The airspeed of 280 m/s (1008 km/h) is also unreasonable for a “commercial airplane” but would be reasonable for a supersonic jet.

Discussion

This problem demonstrates the importance of checking whether calculated results make physical sense. The ground speed of 556 m/s should immediately raise red flags - no commercial aircraft can fly at supersonic speeds. The calculated wind speed of 278 m/s is also physically impossible for Earth’s atmosphere.

Answer

(a) The velocity relative to the ground is 556 m/s (2000 km/h) at 5° south of east

(b) The tailwind velocity is 278 m/s (1000 km/h) at 10° south of east

(c) Both velocities are unreasonably high. The ground speed is supersonic (Mach 1.6), which is impossible for commercial aircraft. The wind speed is 3-4 times stronger than the strongest jet streams ever recorded.

(d) The unreasonable premise is the distance-time relationship (3000 km in 1.50 h), which implies an impossible speed for a commercial airplane.

Construct Your Own Problem

Consider an airplane headed for a runway in a cross wind. Construct a problem in which you calculate the angle the airplane must fly relative to the air mass in order to have a velocity parallel to the runway. Among the things to consider are the direction of the runway, the wind speed and direction (its velocity) and the speed of the plane relative to the air mass. Also calculate the speed of the airplane relative to the ground. Discuss any last minute maneuvers the pilot might have to perform in order for the plane to land with its wheels pointing straight down the runway.