Energy is an important ingredient in all phases of society. We live in a very interdependent world, and access to adequate and reliable energy resources is crucial for economic growth and for maintaining the quality of our lives. But current levels of energy consumption and production are not sustainable. About 40% of the world’s energy comes from oil, and much of that goes to transportation uses. Oil prices are dependent as much upon new (or foreseen) discoveries as they are upon political events and situations around the world. The U.S., with 4.5% of the world’s population, consumes 24% of the world’s oil production per year; 66% of that oil is imported!

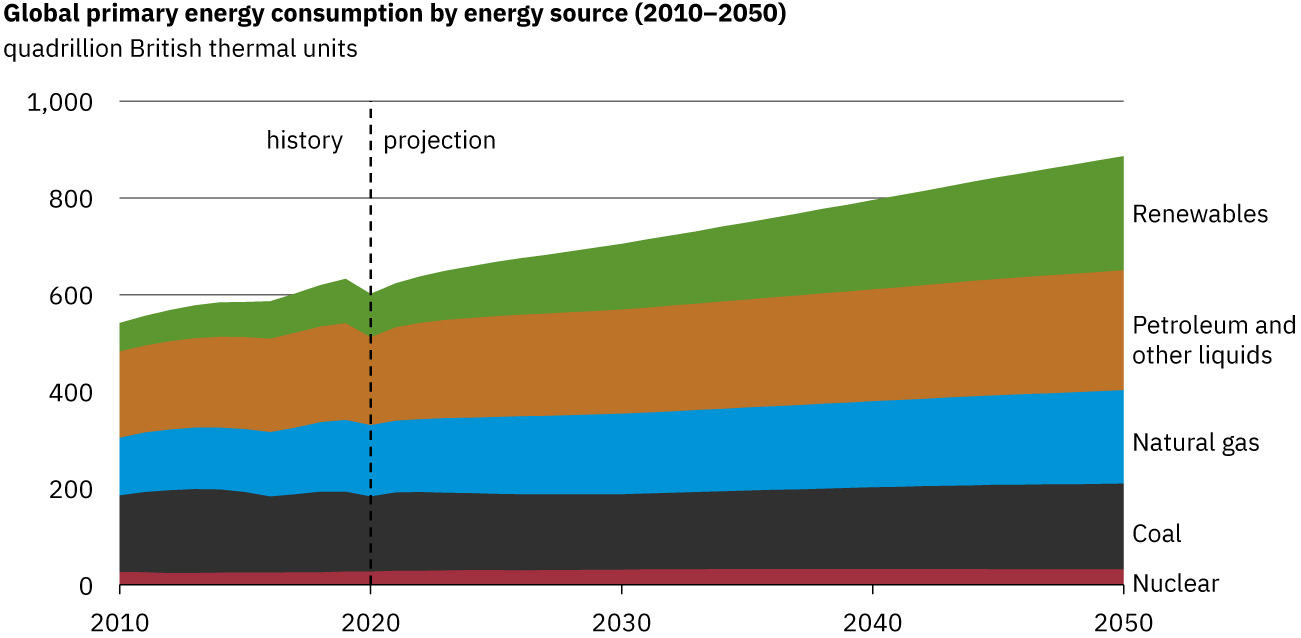

The principal energy resources used in the world are shown in Figure 1. The fuel mix has changed over the years but now is dominated by oil, although natural gas and solar contributions are increasing. Renewable forms of energy are those sources that cannot be used up, such as water, wind, solar, and biomass. About 85% of our energy comes from nonrenewable fossil fuels—oil, natural gas, coal. The likelihood of a link between global warming and fossil fuel use, with its production of carbon dioxide through combustion, has made, in the eyes of many scientists, a shift to non-fossil fuels of utmost importance—but it will not be easy.

World energy consumption continues to rise, especially in the developing countries. ( See Figure 2.) Global demand for energy has tripled in the past 50 years and might triple again in the next 30 years. While much of this growth will come from the rapidly booming economies of China and India, many of the developed countries, especially those in Europe, are hoping to meet their energy needs by expanding the use of renewable sources. Although presently only a small percentage, renewable energy is growing very fast, especially wind energy. For example, Germany plans to meet 65% of its electricity and 30% of its overall energy needs with renewable resources by the year 2030. ( See Figure 3.) Energy is a key constraint in the rapid economic growth of China and India. In 2003, China surpassed Japan as the world’s second largest consumer of oil. However, over 1/3 of this is imported. Unlike most Western countries, coal dominates the commercial energy resources of China, accounting for 2/3 of its energy consumption. In 2009 China surpassed the United States as the largest generator of $\text{CO}\_{2}$. In India, the main energy resources are biomass (wood and dung) and coal. Half of India’s oil is imported. About 70% of India’s electricity is generated by highly polluting coal. Yet there are sizeable strides being made in renewable energy. India has a rapidly growing wind energy base, and it has the largest solar cooking program in the world. China has invested substantially in building solar collection farms as well as hydroelectric plants.

Table 1 displays the 2020 commercial energy mix by country for some of the prime energy users in the world. While non-renewable sources dominate, some countries get a sizeable percentage of their electricity from renewable resources. For example, about two-thirds of New Zealand’s electricity demand is met by hydroelectric. Only 10% of the U.S. electricity is generated by renewable resources, primarily hydroelectric. It is difficult to determine total sources and consumers of energy in many countries, and estimates vary somewhat by data source and type of measurement.

| Country | Consumption in EJ ($10^{18}$ J) | Oil | Natural Gas | Coal | Nuclear | Hydro | Other Renewables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 5.6 | 1.8% | 1.5% | 1.7% | 0% | 0.1% | 0.5% |

| Brazil | 12 | 4.6% | 1.2% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 3.5% | 2% |

| China | 145.5 | 28.5% | 11.9% | 82.3% | 3.3% | 11.7% | 7.8% |

| Egypt | 3.7 | 1.3% | 2.1% | 0.03% | 0% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Germany | 12.1 | 4.2% | 3.1% | 1.9% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 2.2% |

| India | 31.99 | 9% | 2.2% | 17.5% | 0.4% | 1.5% | 1.4% |

| Indonesia | 8.1 | 2.8% | 1.5% | 3.3% | 0% | 0.2% | 0.4% |

| Japan | 17 | 6.5% | 3.8% | 4.6% | 0.4% | 0.7% | 1.1% |

| United Kingdom | 6.9 | 2.4% | 2.6% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 1.2% |

| Russia | 28.3 | 6.4% | 14.8% | 3.2% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 0.5% |

| U.S. | 87.8 | 32.5% | 30% | 9.2% | 7.4% | 2.6% | 6.2% |

The last two columns in this table examine the energy and electricity use per capita. Economic well-being is dependent upon energy use, and in most countries higher standards of living, as measured by GDP (gross domestic product) per capita, are matched by higher levels of energy consumption per capita. This is borne out in Figure 4. Increased efficiency of energy use will change this dependency. A global problem is balancing energy resource development against the harmful effects upon the environment in its extraction and use.

New and diversified energy sources do, however, greatly increase economic opportunity and stability. First, the extensive employment opportunities in renewable energy make it one of the most sustainable and secure fields to enter. Second, renewable energy provides countries and localities with increased levels of resiliency in the face of natural disasters, conflict, or other disruptions. The 21st century has already seen major economic impacts from energy disruptions: Hurricane Katrina, Superstorm Sandy, various wildfires, Hurricane Maria, and the 2021 Texas Winter Storm demonstrate the vulnerability of United States power systems. Diversifying energy sources through renewables and other fossil-fuel alternatives brings power grids and transportation systems back online much more quickly, saving lives and enabling a more swift return to economic operations. And as critical emerging information infrastructure, such as data centers, requires more of the world’s energy, supplying those growing systems during normal operations and crises will be increasingly important.

As we finish this chapter on energy and work, it is relevant to draw some distinctions between two sometimes misunderstood terms in the area of energy use. As has been mentioned elsewhere, the “law of the conservation of energy” is a very useful principle in analyzing physical processes. It is a statement that cannot be proven from basic principles, but is a very good bookkeeping device, and no exceptions have ever been found. It states that the total amount of energy in an isolated system will always remain constant. Related to this principle, but remarkably different from it, is the important philosophy of energy conservation. This concept has to do with seeking to decrease the amount of energy used by an individual or group through (1) reduced activities (e.g., turning down thermostats, driving fewer kilometers) and/or (2) increasing conversion efficiencies in the performance of a particular task—such as developing and using more efficient room heaters, cars that have greater miles-per-gallon ratings, energy-efficient compact fluorescent lights, etc.

Since energy in an isolated system is not destroyed or created or generated, one might wonder why we need to be concerned about our energy resources, since energy is a conserved quantity. The problem is that the final result of most energy transformations is waste heat transfer to the environment and conversion to energy forms no longer useful for doing work. To state it in another way, the potential for energy to produce useful work has been “degraded” in the energy transformation.

What is the difference between energy conservation and the law of conservation of energy? Give some examples of each.

If the efficiency of a coal-fired electrical generating plant is 35%, then what do we mean when we say that energy is a conserved quantity?

Integrated Concepts

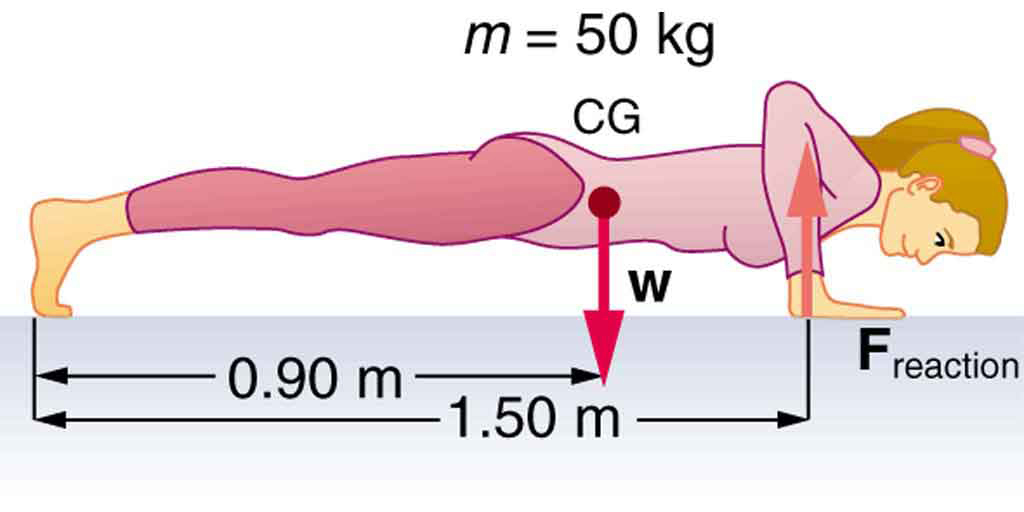

(a) Calculate the force the woman in Figure 5 exerts to do a push-up at constant speed, taking all data to be known to three digits. (b) How much work does she do if her center of mass rises 0.240 m? (c) What is her useful power output if she does 25 push-ups in 1 min? (Should work done lowering her body be included? See the discussion of useful work in Work, Energy, and Power in Humans .

Strategy

For part (a), use torque equilibrium about the feet to find the force on the arms. From the figure, the center of gravity is 0.90 m from the feet, and the arms support the body at 1.50 m from the feet. For part (b), calculate work done against gravity as the center of mass rises. For part (c), find power from total work done in a given time.

Solution

(a) Taking torques about the feet (where normal force acts), with counterclockwise positive:

From the geometry and the given answer, we can deduce the woman’s weight. Solving for F:

If F = 294 N (given in answer), then:

This corresponds to a mass of:

Therefore, the force she exerts on the floor with her arms is:

(b) Work done raising her center of mass 0.240 m:

(c) Power output for 25 push-ups in 1.00 min (60.0 s):

Total work for 25 push-ups:

Discussion

The force exerted by the woman’s arms (294 N) is 60% of her body weight, which makes sense given the lever arm geometry. The work done per push-up (118 J) accounts for raising her center of mass, and the power output of approximately 49 W is reasonable for sustained exercise. Note that work done lowering the body is not included in useful work output, as discussed in the Work, Energy, and Power in Humans section—the muscles are doing negative work while lowering, which doesn’t count toward useful power output.

Answer

(a) The woman exerts a force of 294 N on the floor with her arms.

(b) She does 118 J of work per push-up.

(c) Her useful power output is 49.0 W.

Integrated Concepts

A 75.0-kg cross-country skier is climbing a $3.0^\circ$ slope at a constant speed of 2.00 m/s and encounters air resistance of 25.0 N. Find his power output for work done against the gravitational force and air resistance. (b) What average force does he exert backward on the snow to accomplish this? (c) If he continues to exert this force and to experience the same air resistance when he reaches a level area, how long will it take him to reach a velocity of 10.0 m/s?

Strategy

For part (a), at constant speed, the skier must exert force to overcome both the component of gravity down the slope and air resistance. Power is $P = Fv$.

Solution

(a) Force components and power output:

Force components:

Total force needed:

Power output:

(b) Force exerted backward on the snow:

The force exerted backward on the snow equals the total force needed (from Newton’s third law):

(c) Time to reach 10.0 m/s on level ground:

On level ground, the net force is:

Using $F = ma$:

Time to reach 10.0 m/s from 2.00 m/s:

Discussion

The power output of 127 W is reasonable for sustained moderate exercise like cross-country skiing—it’s roughly equivalent to a 150-W light bulb, which is sustainable for extended periods. The force of approximately 64 N (about 14 lbs) that the skier must push backward is relatively modest, showing that the primary effort is overcoming the gravitational component rather than air resistance at this moderate speed.

Part (c) reveals an interesting result: when the skier reaches level ground while maintaining the same pushing force, the acceleration becomes 0.513 m/s², and it takes 15.6 seconds to reach 10.0 m/s. This demonstrates how much easier it is to maintain speed on level ground compared to climbing a slope—the same force that barely maintains constant speed on the 3° slope produces significant acceleration on flat terrain.

Answer

(a) The skier’s power output is 127 W.

(b) The force exerted backward on the snow is approximately 64 N.

(c) It will take approximately 15.6 seconds to accelerate to 10.0 m/s on level ground.

Integrated Concepts

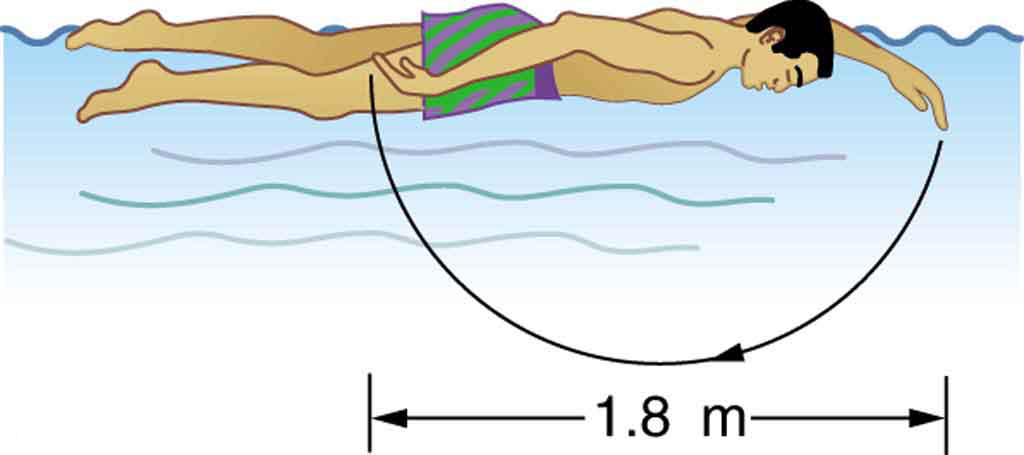

The 70.0-kg swimmer in Figure 6 starts a race with an initial velocity of 1.25 m/s and exerts an average force of 80.0 N backward with his arms during each 1.80 m long stroke. (a) What is his initial acceleration if water resistance is 45.0 N? (b) What is the subsequent average resistance force from the water during the 5.00 s it takes him to reach his top velocity of 2.50 m/s? (c) Discuss whether water resistance seems to increase linearly with velocity.

Strategy

Use Newton’s second law for parts (a) and (b). For part (a), find the initial acceleration. For part (b), use kinematics and work-energy considerations.

Solution

(a) Initial net force and acceleration:

The swimmer exerts 80.0 N backward, water resists with 45.0 N:

(b) Average resistance during acceleration phase:

Using kinematics, find average acceleration from 1.25 m/s to 2.50 m/s in 5.00 s:

The net force is:

Average resistance force:

(c) Since the initial resistance at v = 1.25 m/s was 45.0 N and the average resistance during acceleration was 62.5 N, and the final velocity is 2.50 m/s (double the initial), the resistance increased by more than double. This suggests water resistance increases faster than linearly with velocity—consistent with drag force being proportional to v² at higher speeds.

Discussion

The initial acceleration of 0.500 m/s² is significant but manageable for a competitive swimmer. The increase in water resistance from 45.0 N to an average of 62.5 N during the acceleration phase demonstrates how drag forces increase with velocity. If resistance were linear with velocity (doubling velocity doubles resistance), we’d expect 90 N at v = 2.50 m/s. Since the average is only 62.5 N, and considering that drag is actually proportional to v², this result is physically consistent. At higher swimming speeds, drag becomes the dominant limiting factor, which is why swimmers focus on streamlining techniques to reduce resistance.

Answer

(a) The swimmer’s initial acceleration is 0.500 m/s².

(b) The average water resistance during the acceleration phase is 62.5 N.

(c) Water resistance appears to increase faster than linearly with velocity, consistent with the v² dependence expected for fluid drag.

Integrated Concepts

A toy gun uses a spring with a force constant of 300 N/m to propel a 10.0-g steel ball. If the spring is compressed 7.00 cm and friction is negligible: (a) How much force is needed to compress the spring? (b) To what maximum height can the ball be shot? (c) At what angles above the horizontal may a child aim to hit a target 3.00 m away at the same height as the gun? (d) What is the gun’s maximum range on level ground?

Strategy

The spring’s potential energy converts to kinetic energy, which then converts to potential and/or projectile kinetic energy.

Solution

(a) Maximum force (at full compression):

(b) Maximum height the ball can reach:

Spring potential energy:

At maximum height, all energy is gravitational PE:

(c) Angles to hit a target 3.00 m away:

Initial velocity from spring energy:

For projectile motion with same initial and final height:

Solving for angle when $R = 3.00\m$:

(d) Maximum range on level ground:

Maximum range occurs at $\theta = 45^\circ$:

Discussion

The maximum force of 21.0 N (about 4.7 lbs) is easily achievable for compressing a toy gun spring. The maximum height of 7.50 m is impressive for a toy—equivalent to a 2.5-story building! The two possible angles to hit a target (5.8° and 84.2°) demonstrate a fundamental property of projectile motion: any target within range can be hit at two complementary angles, one nearly horizontal and one nearly vertical. The low-angle shot reaches the target quickly, while the high-angle shot has a much longer flight time. The maximum range of 14.9 m (about 49 feet) shows this is quite a powerful toy gun, emphasizing why such toys need appropriate safety precautions.

Answer

(a) A force of 21.0 N is needed to fully compress the spring.

(b) The ball can reach a maximum height of 7.50 m when shot straight up.

(c) The child can aim at 5.8° or 84.2° above horizontal to hit the target.

(d) The gun’s maximum range on level ground is 14.9 m.

Integrated Concepts

(a) What force must be supplied by an elevator cable to produce an acceleration of $0.800\mss$ against a 200-N frictional force, if the mass of the loaded elevator is 1500 kg? (b) How much work is done by the cable in lifting the elevator 20.0 m? (c) What is the final speed of the elevator if it starts from rest? (d) How much work went into thermal energy?

Strategy

Use Newton’s second law for part (a). For parts (b)-(d), use work-energy relationships.

Solution

(a) Using Newton’s second law (upward positive):

(b) Work done by the cable:

(c) Final speed using kinematics ($v_{0} = 0$):

(d) Work done against friction (thermal energy):

Discussion

The cable must exert 16,100 N, which is about 1.1 times the elevator’s weight, to provide the upward acceleration against friction. The total work of 322 kJ can be broken down into components: gravitational potential energy (294 kJ), kinetic energy (24 kJ), and thermal energy from friction (4.00 kJ). The final speed of 5.66 m/s (about 12.7 mph) is typical for elevators, providing a balance between efficiency and passenger comfort. The relatively small amount of energy lost to friction (about 1.2% of total work) indicates that modern elevator systems are quite efficient, though in practice, additional energy losses occur in the motor and cable system.

Answer

(a) The elevator cable must supply a force of 16,100 N (or 16.1 kN).

(b) The cable does 322 kJ of work in lifting the elevator 20.0 m.

(c) The final speed of the elevator is 5.66 m/s.

(d) 4.00 kJ of work is converted to thermal energy due to friction.

Unreasonable Results

A car advertisement claims that its 900-kg car accelerated from rest to 30.0 m/s and drove 100 km, gaining 3.00 km in altitude, on 1.0 gal of gasoline. The average force of friction including air resistance was 700 N. Assume all values are known to three significant figures. (a) Calculate the car’s efficiency. (b) What is unreasonable about the result? (c) Which premise is unreasonable, or which premises are inconsistent?

Strategy

Calculate the total energy needed (kinetic + potential + work against friction) and compare to the energy available from 1.0 gallon of gasoline ($1.2 \times 10^{8}$ J from Table 1 in Conservation of Energy).

Solution

(a) Energy components needed:

Kinetic energy:

Potential energy gained:

Work done against friction:

Total energy needed:

Energy available from gasoline:

Efficiency:

Discussion

The calculated efficiency of 81% is unreasonably high and violates fundamental thermodynamic principles. Real gasoline engines are limited by the Carnot efficiency and practical considerations to about 25-30% efficiency, while the best diesel engines achieve 35-40%. Even the most efficient production cars (hybrid electric vehicles) rarely exceed 40% efficiency. An 81% efficiency would mean that only 19% of the fuel’s energy is lost to heat, which contradicts the second law of thermodynamics for heat engines operating at these temperature ranges.

The claim is inconsistent with physical reality. Several factors reveal the impossibility:

First, gaining 3.00 km (about 1.86 miles) of altitude while traveling 100 km represents an average grade of 3%, which combined with overcoming friction over such distance requires substantial energy. Second, achieving a final speed of 30.0 m/s (67 mph) adds kinetic energy. The total energy requirement of 96.9 MJ is close to what 1.0 gallon of gasoline can provide (120 MJ), but this would require near-perfect efficiency—impossible for any heat engine.

In reality, such a trip would require approximately 3-4 gallons of gasoline for a typical car, or about 1.5-2 gallons for a highly efficient hybrid vehicle. The advertising claim is clearly false and misleading.

Answer

(a) The claimed efficiency is 80.8%.

(b) This efficiency is unreasonably high—it violates thermodynamic limitations for heat engines and exceeds the efficiency of any real vehicle by a factor of 2-3.

(c) The premises are inconsistent. The fuel consumption of 1.0 gallon is far too low for the described trip. Realistically, this trip would require 3-4 gallons of gasoline for a conventional car.

Unreasonable Results

Body fat is metabolized, supplying 9.30 kcal/g, when dietary intake is less than needed to fuel metabolism. The manufacturers of an exercise bicycle claim that you can lose 0.500 kg of fat per day by vigorously exercising for 2.00 h per day on their machine. (a) How many kcal are supplied by the metabolization of 0.500 kg of fat? (b) Calculate the kcal/min that you would have to utilize to metabolize fat at the rate of 0.500 kg in 2.00 h. (c) What is unreasonable about the results? (d) Which premise is unreasonable, or which premises are inconsistent?

Strategy

For part (a), multiply the mass of fat by the energy content per gram. For part (b), divide the total energy by the time in minutes. For parts (c) and (d), compare the calculated power output to realistic human metabolic rates from Table 2 in Work Energy And Power In Humans.

Solution

(a) Energy from metabolizing 0.500 kg of fat:

(b) Time available: 2.00 h = 120 min

Energy utilization rate needed:

(c) and (d) According to Table 2 in Work Energy And Power In Humans, the highest sustainable metabolic rate listed is approximately 35 kcal/min for sprinting, which corresponds to about 2415 watts. The required rate of 38.8 kcal/min exceeds even this maximum sprint value.

Discussion

The claim that one can lose 0.500 kg of fat in 2.00 hours through vigorous exercise is physiologically unreasonable. The required metabolic rate of 38.8 kcal/min exceeds the maximum human power output for sprinting (about 35 kcal/min), and more importantly, no one can maintain a sprinting pace for 2 hours.

For context, elite marathon runners maintain approximately 15-20 kcal/min for 2+ hours, and even elite cyclists in races like the Tour de France average about 20-25 kcal/min over several hours. The manufacturer’s claim would require maintaining a power output higher than an all-out sprint for 120 minutes, which is physiologically impossible.

A realistic fat loss rate through exercise would be about 0.1-0.2 kg per 2-hour vigorous workout, not 0.500 kg. The manufacturer’s claim exaggerates the possible fat loss by a factor of 3-5.

Answer

(a) Metabolizing 0.500 kg of fat supplies 4650 kcal (or 4.65 × 10³ kcal).

(b) You would need to metabolize fat at a rate of 38.8 kcal/min.

(c) This rate exceeds the maximum human power output for sprinting and is unreasonably high for any sustained activity.

(d) The premise is unreasonable—it is physiologically impossible to maintain this power output for 2 hours. Realistic fat loss would be about 0.1-0.2 kg per 2-hour session, not 0.500 kg.

Construct Your Own Problem

Consider a person climbing and descending stairs. Construct a problem in which you calculate the long-term rate at which stairs can be climbed considering the mass of the person, his ability to generate power with his legs, and the height of a single stair step. Also consider why the same person can descend stairs at a faster rate for a nearly unlimited time in spite of the fact that very similar forces are exerted going down as going up. (This points to a fundamentally different process for descending versus climbing stairs.)

Guidance for Constructing This Problem

When constructing this problem, consider the following framework:

Strategy

Use the relationship between power, work, and time. The work done climbing stairs is primarily against gravity (W = mgh), while descending involves negative work. Compare energy requirements for ascending versus descending.

Key Parameters to Define:

Calculations to Include:

where h is the total height climbed in time t

Determine how many steps can be climbed per minute given the person’s sustainable power output

Discussion Points:

Example Answer:

For a 70 kg person with sustainable power output of 175 W climbing stairs with 0.20 m step height:

Construct Your Own Problem

Consider humans generating electricity by pedaling a device similar to a stationary bicycle. Construct a problem in which you determine the number of people it would take to replace a large electrical generation facility. Among the things to consider are the power output that is reasonable using the legs, rest time, and the need for electricity 24 hours per day. Discuss the practical implications of your results.

Guidance for Constructing This Problem

When constructing this problem, consider the following framework:

Strategy

Calculate the total power output needed from a large power plant, then determine how many people pedaling continuously would be required. Account for human limitations including sustainable power output, rest requirements, and 24-hour operation.

Key Parameters to Define:

Calculations to Include:

Calculate shift requirements for 24/7 operation

Discussion Points:

Example Answer:

For a 1000 MW (1 × 10⁹ W) power plant:

This demonstrates why human-powered electricity generation is impractical at scale—it would require enormous numbers of people and consume more energy (in food) than it produces.

Integrated Concepts

A 105-kg basketball player crouches down 0.400 m while waiting to jump. After exerting a force on the floor through this 0.400 m, their feet leave the floor and their center of gravity rises 0.950 m above its normal standing erect position. (a) Using energy considerations, calculate the player’s velocity when they leave the floor. (b) What average force did the player exert on the floor? (Do not neglect the force to support their weight as well as that to accelerate them.) (c) What was the player’s power output during the acceleration phase?

Strategy

Use energy conservation for part (a). For part (b), use work-energy theorem over the crouch distance. For part (c), calculate power from work and time.

Solution

(a) Using energy conservation (KE at takeoff converts to PE at max height):

(b) The player’s legs must do work to give the body kinetic energy plus work against gravity over the 0.400 m crouch:

Net work needed:

The average force must support the player’s weight plus provide the net acceleration force:

(c) Power output during acceleration:

Time during crouch (using kinematics with $v_{\text{avg}} = v/2$):

Total work done by legs (including against gravity):

Power:

Discussion

The takeoff velocity of 4.32 m/s (about 9.7 mph) is reasonable for a professional basketball player performing a vertical jump. This speed translates to rising 0.950 m (about 3.1 feet) above the standing position, which represents an excellent vertical jump—typical professional players achieve 24-36 inches of vertical leap.

The average force of 3470 N is particularly noteworthy—it’s about 3.4 times the player’s body weight. This demonstrates the tremendous forces that athletes’ legs must generate during explosive movements. The force is distributed between both legs, so each leg experiences about 1735 N (390 lbs), which while substantial, is within the capability of well-trained athletes.

The power output calculation reveals an interesting discrepancy. Using average velocity gives approximately 7.5 kW, but accounting for the non-uniform acceleration (the force isn’t constant during the jump—it starts high and decreases) gives a peak power of approximately 8.93 kW (about 12 horsepower). This enormous power output is only sustainable for a fraction of a second, which is characteristic of explosive athletic movements. For comparison, this is about 50 times the sustained power output a person can maintain while cycling. Such high peak power outputs are possible because they draw on immediate energy stores (ATP and creatine phosphate) in the muscles, which are quickly depleted.

The efficiency of this movement is also worth noting—the player’s muscles must generate significantly more than the 1388 J of mechanical work due to the ~25% efficiency of muscle contraction, meaning the actual metabolic energy expended is approximately 5500 J or about 1.3 food calories per jump.

Answer

(a) The player’s takeoff velocity is 4.32 m/s (approximately 9.7 mph).

(b) The average force exerted on the floor is 3470 N (about 780 lbs or 3.4 times body weight).

(c) The player’s power output during the acceleration phase is approximately 8.93 kW (about 12 hp), achievable for brief explosive movements.