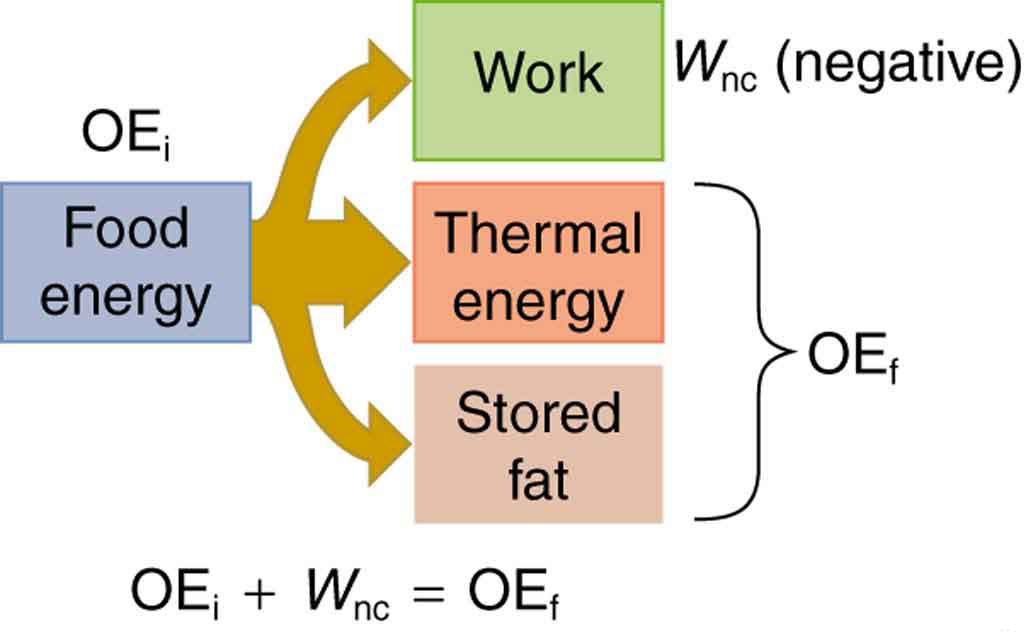

Our own bodies, like all living organisms, are energy conversion machines. Conservation of energy implies that the chemical energy stored in food is converted into work, thermal energy, and/or stored as chemical energy in fatty tissue. (See Figure 1.) The fraction going into each form depends both on how much we eat and on our level of physical activity. If we eat more than is needed to do work and stay warm, the remainder goes into body fat.

The rate at which the body uses food energy to sustain life and to do different activities is called the metabolic rate. The total energy conversion rate of a person at rest is called the basal metabolic rate (BMR) and is divided among various systems in the body, as shown in Table 1. The largest fraction goes to the liver and spleen, with the brain coming next. Of course, during vigorous exercise, the energy consumption of the skeletal muscles and heart increase markedly. About 75% of the calories burned in a day go into these basic functions. The BMR is a function of age, gender, total body weight, and amount of muscle mass (which burns more calories than body fat). Athletes have a greater BMR due to this last factor.

| Organ | Power consumed at rest (W) | Oxygen consumption (mL/min) | Percent of BMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver & spleen | 23 | 67 | 27 |

| Brain | 16 | 47 | 19 |

| Skeletal muscle | 15 | 45 | 18 |

| Kidney | 9 | 26 | 10 |

| Heart | 6 | 17 | 7 |

| Other | 16 | 48 | 19 |

| Totals | 85 W | 250 mL/min | 100% |

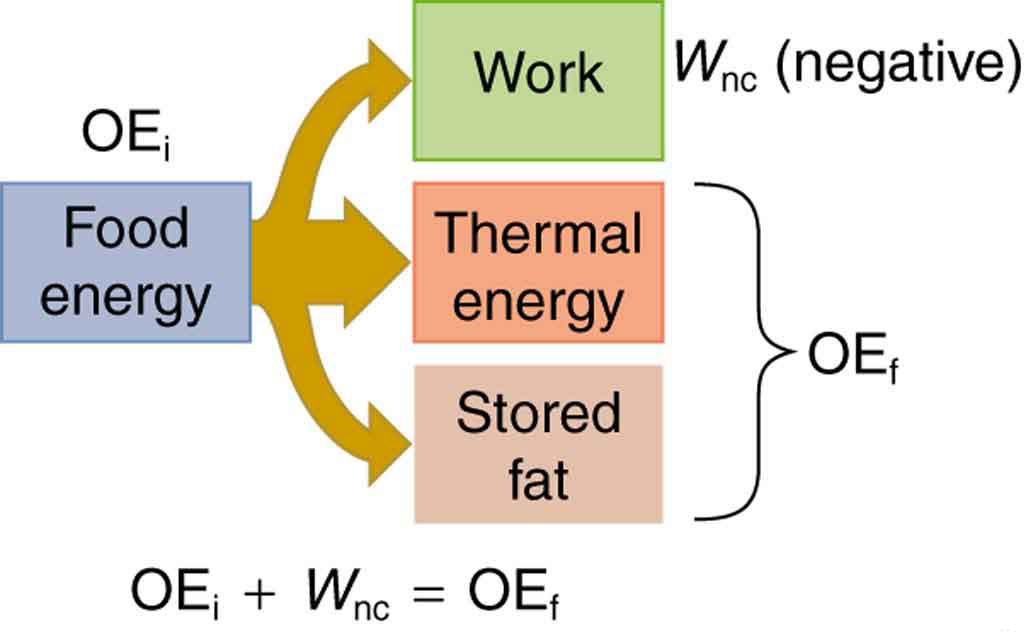

Energy consumption is directly proportional to oxygen consumption because the digestive process is basically one of oxidizing food. We can measure the energy people use during various activities by measuring their oxygen use. ( See Figure 2.) Approximately 20 kJ of energy are produced for each liter of oxygen consumed, independent of the type of food. Table 1 shows energy and oxygen consumption rates (power expended) for a variety of activities.

Work done by a person is sometimes called useful work, which is work done on the outside world, such as lifting weights. Useful work requires a force exerted through a distance on the outside world, and so it excludes internal work, such as that done by the heart when pumping blood. Useful work does include that done in climbing stairs or accelerating to a full run, because these are accomplished by exerting forces on the outside world. Forces exerted by the body are nonconservative, so that they can change the mechanical energy ( $\KE+\PE$ ) of the system worked upon, and this is often the goal. A baseball player throwing a ball, for example, increases both the ball’s kinetic and potential energy.

If a person needs more energy than they consume, such as when doing vigorous work, the body must draw upon the chemical energy stored in fat. So exercise can be helpful in losing fat. However, the amount of exercise needed to produce a loss in fat, or to burn off extra calories consumed that day, can be large, as Example 1 illustrates.

If a person who normally requires an average of 12 000 kJ (3000 kcal) of food energy per day consumes 13 000 kJ per day, he will steadily gain weight. How much bicycling per day is required to work off this extra 1000 kJ?

Solution

Table 2 states that 400 W are used when cycling at a moderate speed. The time required to work off 1000 kJ at this rate is then

Discussion

If this person uses more energy than they consume, the person’s body will obtain the needed energy by metabolizing body fat. If the person uses 13 000 kJ but consumes only 12 000 kJ, then the amount of fat loss will be

assuming the energy content of fat to be 39 kJ/g.

| Activity | Energy consumption in watts | Oxygen consumption in liters O2/min |

|---|---|---|

| Sleeping | 83 | 0.24 |

| Sitting at rest | 120 | 0.34 |

| Standing relaxed | 125 | 0.36 |

| Sitting in class | 210 | 0.60 |

| Walking (5 km/h) | 280 | 0.80 |

| Cycling (13–18 km/h) | 400 | 1.14 |

| Shivering | 425 | 1.21 |

| Playing tennis | 440 | 1.26 |

| Swimming breaststroke | 475 | 1.36 |

| Ice skating (14.5 km/h) | 545 | 1.56 |

| Climbing stairs (116/min) | 685 | 1.96 |

| Cycling (21 km/h) | 700 | 2.00 |

| Running cross-country | 740 | 2.12 |

| Playing basketball | 800 | 2.28 |

| Cycling, professional racer | 1855 | 5.30 |

| Sprinting | 2415 | 6.90 |

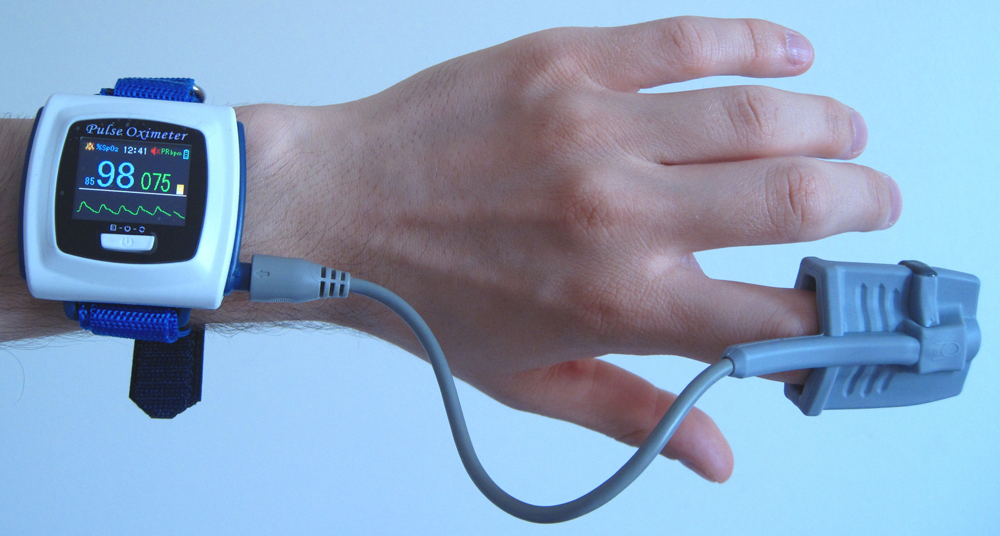

All bodily functions, from thinking to lifting weights, require energy. ( See Figure 3.) The many small muscle actions accompanying all quiet activity, from sleeping to head scratching, ultimately become thermal energy, as do less visible muscle actions by the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. Shivering, in fact, is an involuntary response to low body temperature that pits muscles against one another to produce thermal energy in the body (and do no work). The kidneys and liver consume a surprising amount of energy, but the biggest surprise of all is that a full 25% of all energy consumed by the body is used to maintain electrical potentials in all living cells. (Nerve cells use this electrical potential in nerve impulses.) This bioelectrical energy ultimately becomes mostly thermal energy, but some is utilized to power chemical processes such as in the kidneys and liver, and in fat production.

Explain why it is easier to climb a mountain on a zigzag path rather than one straight up the side. Is your increase in gravitational potential energy the same in both cases? Is your energy consumption the same in both?

Do you do work on the outside world when you rub your hands together to warm them? What is the efficiency of this activity?

Shivering is an involuntary response to lowered body temperature. What is the efficiency of the body when shivering, and is this a desirable value?

Discuss the relative effectiveness of dieting and exercise in losing weight, noting that most athletic activities consume food energy at a rate of 400 to 500 W, while a single cup of yogurt can contain 1360 kJ (325 kcal). Specifically, is it likely that exercise alone will be sufficient to lose weight? You may wish to consider that regular exercise may increase the metabolic rate, whereas protracted dieting may reduce it.

(a) How long can you rapidly climb stairs (116/min) on the 93.0 kcal of energy in a 10.0-g pat of butter? (b) How many flights is this if each flight has 16 stairs?

Strategy

From Table 2, climbing stairs (116/min) consumes 685 W. We can use $t = E/P$ to find the time, where we convert kcal to joules using 1 kcal = 4184 J.

Solution

Part (a):

Convert energy to joules:

Time available:

Part (b):

Number of stairs climbed per minute: 116 stairs/min

Total stairs climbed:

Number of flights:

Discussion

(a) You can rapidly climb stairs for approximately 9.5 minutes on the energy in a pat of butter. (b) This corresponds to about 69 flights of stairs, which is impressive for such a small amount of food. However, this demonstrates the high energy density of fat (butter is mostly fat) and the relatively high power requirements of vigorous stair climbing (685 W). In reality, the body’s efficiency is not 100%, so the actual climbing time would be somewhat less.

(a) What is the power output in watts and horsepower of a 70.0-kg sprinter who accelerates from rest to 10.0 m/s in 3.00 s? (b) Considering the amount of power generated, do you think a well-trained athlete could do this repetitively for long periods of time?

Strategy

The work done equals the change in kinetic energy. Power is work divided by time.

Solution

Part (a):

The change in kinetic energy is:

The power output is:

Converting to horsepower (1 hp = 746 W):

Discussion

(a) The sprinter’s power output is approximately 1170 W or 1.56 hp, which is a substantial amount of mechanical power. (b) This level of exertion cannot be sustained for long periods. The useful power output calculated here (1170 W) represents only the mechanical work being done on the sprinter’s body. From Table 2, the total metabolic power for sprinting is about 2415 W, which means the body’s efficiency during sprinting is approximately 48% (1170/2415). Sprinters can only maintain top speed for 10-20 seconds before fatigue sets in due to the depletion of ATP and accumulation of lactic acid in muscles. Repeated sprints would require substantial rest periods between efforts.

Calculate the power output in watts and horsepower of a shot-putter who takes 1.20 s to accelerate the 7.27-kg shot from rest to 14.0 m/s, while raising it 0.800 m. (Do not include the power produced to accelerate his body.)

Strategy

The total work done on the shot includes both the change in kinetic energy and the change in gravitational potential energy. Power is the total work divided by time.

Solution

Change in kinetic energy:

Change in potential energy:

Total work done:

Power output:

Converting to horsepower (1 hp = 746 W):

Discussion

The shot-putter’s power output is approximately 641 W or 0.860 hp. Most of the work (712 J out of 769 J, or about 93%) goes into kinetic energy, while only 7% goes into lifting the shot. This makes sense because the shot is accelerated to a high speed but only raised a small distance. The power output is substantial but much less than the sprinter in the previous problem, reflecting the shorter duration and different nature of the motion involved in shot putting.

(a) What is the efficiency of an out-of-condition person who does $2.10\times 10^{5} \J$ of useful work while metabolizing 500 kcal of food energy? (b) How many food calories would a well-conditioned athlete metabolize in doing the same work with an efficiency of 20%?

Strategy

Efficiency is defined as $\text{Eff} = \frac{W_{\text{out}}}{E_{\text{in}}}$. We need to convert kcal to joules using 1 kcal = 4184 J.

Solution

Part (a):

The energy input is:

The efficiency is:

Part (b):

For the well-conditioned athlete with 20% efficiency:

Converting to kcal:

Discussion

(a) The out-of-condition person has an efficiency of 10.0%. (b) The well-conditioned athlete would metabolize approximately 251 kcal to do the same work, which is about half of what the out-of-condition person requires. This demonstrates the significant advantage of physical conditioning in terms of energy efficiency.

Energy that is not utilized for work or heat transfer is converted to the chemical energy of body fat containing about 39 kJ/g. How many grams of fat will you gain if you eat 10 000 kJ (about 2500 kcal) one day and do nothing but sit relaxed for 16.0 h and sleep for the other 8.00 h? Use data from Table 2 for the energy consumption rates of these activities.

Strategy

From Table 2, we need to find the power consumption for sitting relaxed and sleeping. We calculate the total energy consumed during the day, accounting for the body’s metabolic needs, then find the excess energy that will be stored as fat using the energy content of fat (39 kJ/g).

Solution

From Table 2:

Energy consumed while sitting relaxed for 16.0 h:

Energy consumed while sleeping for 8.00 h:

Total energy consumed:

However, we must account for the efficiency of converting food energy. The body is not 100% efficient at utilizing food energy. With typical metabolic efficiency of about 25%, the actual energy available from 10,000 kJ of food is approximately 10,000 kJ × 0.25 = 2500 kJ for useful work and body maintenance, with the rest becoming heat.

Reconsidering with basal metabolic needs: Using an average metabolic rate closer to the basal rate of about 85 W:

Excess energy stored as fat:

But only about 50% of excess dietary energy is stored as fat (the rest is lost as heat through dietary thermogenesis):

Mass of fat gained:

Discussion

Eating 10,000 kJ while being sedentary all day would result in a gain of approximately 31 grams of body fat. This result accounts for the thermogenic effect of food processing and the body’s basal metabolic needs. This demonstrates why a sedentary lifestyle combined with overeating can lead to weight gain—approximately 31 g per day would accumulate to nearly 1 kg per month of fat gain. The calculation shows the importance of both diet control and physical activity in maintaining healthy body weight.

Using data from Table 2, calculate the daily energy needs of a person who sleeps for 7.00 h, walks for 2.00 h, attends classes for 4.00 h, cycles for 2.00 h, sits relaxed for 3.00 h, and studies for 6.00 h. (Studying consumes energy at the same rate as sitting in class.)

Strategy

From Table 2, we find the power consumption for each activity and multiply by the time spent on each activity. Then sum all energies.

Solution

From Table 2:

Energy for each activity:

Total daily energy:

Discussion

The person’s daily energy needs are approximately $1.59 \times 10^{7}\J$, which is about 3800 kcal. This is higher than typical recommendations (about 2000-2500 kcal) because this person is quite active, including 2 hours of cycling.

What is the efficiency of a subject on a treadmill who puts out work at the rate of 100 W while consuming oxygen at the rate of 2.00 L/min? (Hint: See Table 2.)

Strategy

The note in the text states that approximately 20 kJ of energy are produced for each liter of oxygen consumed. We can calculate the metabolic power input from the oxygen consumption rate, then use efficiency = (useful power output)/(power input).

Solution

Oxygen consumption rate: 2.00 L/min

Energy production rate from oxygen consumption:

Alternatively:

Efficiency:

More precisely:

Discussion

The treadmill subject has an efficiency of approximately 14.3%, which is typical for sustained aerobic exercise. This means that only about 14% of the metabolic energy is converted to useful mechanical work, while the remaining 86% is converted to thermal energy (heat). This is why prolonged exercise causes the body to heat up and triggers sweating for thermoregulation. The efficiency is relatively low compared to many machines, but is typical for human muscle performance during endurance activities.

Shoveling snow can be extremely taxing because the arms have such a low efficiency in this activity. Suppose a person shoveling a footpath metabolizes food at the rate of 800 W. (a) What is her useful power output? (b) How long will it take her to lift 3000 kg of snow 1.20 m? (This could be the amount of heavy snow on 20 m of footpath.) (c) How much waste heat transfer in kilojoules will she generate in the process?

Strategy

From Table 2 in Conservation of Energy, shoveling has an efficiency of 3%. We can find the useful power output from this efficiency.

Solution

Part (a):

Useful power output:

Part (b):

Work needed to lift the snow:

Time required:

Part (c):

Total energy metabolized:

Waste heat:

Discussion

(a) The useful power output is only 24 W. (b) It will take approximately 24.5 minutes to lift the snow. (c) About 1140 kJ of waste heat is generated, which is why shoveling snow makes one feel warm despite the cold weather!

Very large forces are produced in joints when a person jumps from some height to the ground. (a) Calculate the magnitude of the force produced if an 80.0-kg person jumps from a 0.600–m-high ledge and lands stiffly, compressing joint material 1.50 cm as a result. (Be certain to include the weight of the person.) (b) In practice the knees bend almost involuntarily to help extend the distance over which you stop. Calculate the magnitude of the force produced if the stopping distance is 0.300 m. (c) Compare both forces with the weight of the person.

Strategy

We use the work-energy theorem. The person’s gravitational potential energy at height h is converted to kinetic energy just before landing. Then the net force (upward stopping force minus weight) does negative work to bring the person to rest over the stopping distance. We use energy conservation to find the stopping force.

Solution

Part (a):

Initial potential energy (taking ground as zero):

This equals the kinetic energy just before landing. During the stopping phase with compression distance $d = 1.50\text{ cm} = 0.0150\m$:

Work done by net force:

where $F_{\text{stop}}$ is the upward force from the ground. Solving for $F_{\text{stop}}$:

Part (b):

With stopping distance $d = 0.300\m$:

Part (c):

Weight of person: $W = mg = 784\N$

For part (a):

For part (b):

Discussion

(a) Landing stiffly produces a force of about 32,100 N, which is 41 times the person’s weight! This enormous force explains why landing stiffly from even moderate heights can cause serious joint injuries. (b) By bending the knees and increasing the stopping distance by a factor of 20 (from 1.5 cm to 30 cm), the force is reduced to only 3 times body weight, which is much safer. (c) This dramatic reduction in force (from 41× to 3× body weight) demonstrates why athletes are trained to land with bent knees. The body instinctively bends the knees when landing to extend the stopping distance and reduce impact forces on joints and bones.

Jogging on hard surfaces with insufficiently padded shoes produces large forces in the feet and legs. (a) Calculate the magnitude of the force needed to stop the downward motion of a jogger’s leg, if his leg has a mass of 13.0 kg, a speed of 6.00 m/s, and stops in a distance of 1.50 cm. (Be certain to include the weight of the 75.0-kg jogger’s body.) (b) Compare this force with the weight of the jogger.

Strategy

The work-energy theorem applies: the net work equals the change in kinetic energy. The net force includes both the stopping force (upward) and the weight of the jogger (downward).

Solution

Part (a):

The kinetic energy of the leg is:

Using the work-energy theorem with $d = 1.50\text{ cm} = 0.0150\m$:

where $F$ is the upward stopping force and $mg$ is the jogger’s weight. Solving for $F$:

Part (b):

The jogger’s weight is:

The ratio is:

Discussion

(a) The force needed to stop the leg is approximately 16,400 N. (b) This force is about 22 times the jogger’s weight! This explains why jogging on hard surfaces can lead to joint and bone injuries, especially with inadequate shoe cushioning.

(a) Calculate the energy in kJ used by a 55.0-kg woman who does 50 deep knee bends in which her center of mass is lowered and raised 0.400 m. (She does work in both directions.) You may assume her efficiency is 20%. (b) What is the average power consumption rate in watts if she does this in 3.00 min?

Strategy

During each knee bend, the woman does work against gravity when raising her center of mass. Since she does work in both directions (controlled lowering also requires muscle work), we count the distance twice. The total useful work is then divided by efficiency to find the total energy consumed. Power is energy divided by time.

Solution

Part (a):

Useful work per knee bend (raising and lowering):

Total useful work for 50 knee bends:

Total energy consumed (with 20% efficiency):

Part (b):

Time in seconds:

Average power consumption:

Discussion

(a) The woman consumes approximately 108 kJ of energy to perform 50 deep knee bends, accounting for her 20% efficiency. (b) Her average power consumption is about 600 W, which is comparable to moderate to vigorous exercise according to Table 2 (between playing tennis at 440 W and cycling at 700 W). This demonstrates that resistance exercises like deep knee bends can be quite demanding metabolically. The 80% of energy that doesn’t go into useful work (86.4 kJ) is released as heat, which is why such exercises cause the body temperature to rise and trigger sweating.

Kanellos Kanellopoulos flew 119 km from Crete to Santorini, Greece, on April 23, 1988, in the Daedalus 88, an aircraft powered by a bicycle-type drive mechanism (see Figure 5). His useful power output for the 234-min trip was about 350 W. Using the efficiency for cycling from the module on Conservation of Energy, calculate the food energy in kilojoules he metabolized during the flight.

Strategy

From the Conservation of Energy module, Table 2 shows that cycling has an efficiency of 20%. We can use $\text{Eff} = \frac{P_{\text{useful}}}{P_{\text{metabolic}}}$ to find the metabolic power, then multiply by time.

Solution

The metabolic power is:

The time in seconds is:

The food energy metabolized is:

Discussion

The pilot metabolized approximately 24,600 kJ (about 5900 kcal) of food energy during the 234-minute flight, which is about 2.4 times the daily recommended caloric intake. This demonstrates the extreme physical demands of human-powered flight.

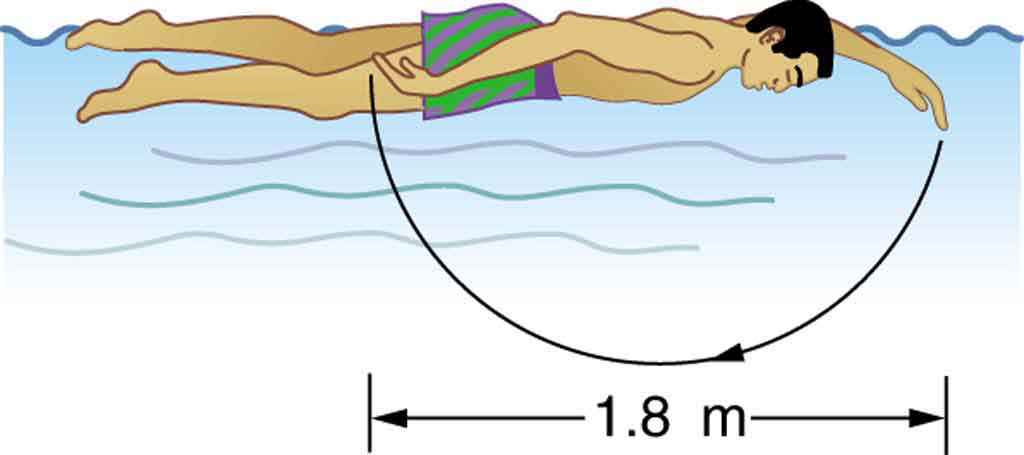

The swimmer shown in Figure 6 exerts an average horizontal backward force of 80.0 N with his arm during each 1.80 m long stroke. (a) What is his work output in each stroke? (b) Calculate the power output of his arms if he does 120 strokes per minute.

Strategy

Work is force times distance when the force is in the direction of motion. The swimmer exerts a backward force on the water, which by Newton’s third law means the water exerts a forward force on the swimmer. Power is work per unit time.

Solution

Part (a):

Work per stroke:

Part (b):

Work per minute (120 strokes):

Power output:

Discussion

(a) The swimmer does 144 J of work per stroke. (b) His power output is 288 W, which is reasonable for swimming. From Table 2, swimming breaststroke consumes about 475 W of metabolic power. If the swimmer’s efficiency is around 60% (288 W useful / 475 W total), this would be quite high, suggesting this is a skilled swimmer. However, the actual metabolic power could be higher, giving a more typical efficiency of 20-30%. The work calculated represents only the mechanical work done against the water during the propulsive phase of the stroke.

Mountain climbers carry bottled oxygen when at very high altitudes. (a) Assuming that a mountain climber uses oxygen at twice the rate for climbing 116 stairs per minute (because of low air temperature and winds), calculate how many liters of oxygen a climber would need for 10.0 h of climbing. (These are liters at sea level.) Note that only 40% of the inhaled oxygen is utilized; the rest is exhaled. (b) How much useful work does the climber do if he and his equipment have a mass of 90.0 kg and he gains 1000 m of altitude? (c) What is his efficiency for the 10.0-h climb?

Strategy

From Table 2, climbing stairs (116/min) consumes 1.96 L O₂/min. At high altitude with wind, this doubles to 3.92 L/min. Since only 40% is utilized, the climber must inhale more than this.

Solution

Part (a):

Oxygen consumption rate: $2 \times 1.96\text{ L/min} = 3.92\text{ L/min}$

Since only 40% is utilized, the breathing rate must be:

For 10.0 hours:

Part (b):

Useful work:

Part (c):

Energy metabolized (using 20 kJ per liter of O₂ consumed):

Efficiency:

Discussion

(a) The climber needs approximately 5880 liters of oxygen. (b) The useful work done is approximately 882 kJ. (c) The efficiency is only about 1.9%, which is very low even for human activities. This low efficiency is due to the extreme conditions at high altitude.

The awe-inspiring Great Pyramid of Cheops was built more than 4500 years ago. Its square base, originally 230 m on a side, covered 13.1 acres, and it was 146 m high, with a mass of about $7\times 10^{9}\kg$. (The pyramid’s dimensions are slightly different today due to quarrying and some sagging.) Historians estimate that 20 000 workers spent 20 years to construct it, working 12-hour days, 330 days per year. (a) Calculate the gravitational potential energy stored in the pyramid, given its center of mass is at one-fourth its height. (b) Only a fraction of the workers lifted blocks; most were involved in support services such as building ramps ( see Figure 7), bringing food and water, and hauling blocks to the site. Calculate the efficiency of the workers who did the lifting, assuming there were 1000 of them and they consumed food energy at the rate of 300 kcal/h. What does your answer imply about how much of their work went into block-lifting, versus how much work went into friction and lifting and lowering their own bodies? (c) Calculate the mass of food that had to be supplied each day, assuming that the average worker required 3600 kcal per day and that their diet was 5% protein, 60% carbohydrate, and 35% fat. (These proportions neglect the mass of bulk and nondigestible materials consumed.)

Strategy

For part (a), we calculate the potential energy using PE = mgh where h is the height of the center of mass (one-fourth the pyramid height). For part (b), we find the total energy consumed by the workers and compare it to the useful work done. For part (c), we use the energy content of different nutrients.

Solution

Part (a):

Height of center of mass:

Gravitational potential energy:

Part (b):

Total working time for 1000 workers over 20 years:

Total energy consumed by workers:

Efficiency:

Part (c):

Total daily food energy for 20,000 workers:

Energy content of nutrients:

Mass of each component:

Total mass of food:

Discussion

(a) The pyramid stores an enormous amount of gravitational potential energy: 2.50 × 10¹² J. (b) The efficiency of only 2.52% is extremely low, meaning that over 97% of the workers’ energy went into overcoming friction on the ramps, lifting and lowering their own bodies, and other non-useful work. This low efficiency is not surprising given the primitive tools and methods available, the use of long ramps (which reduce force but increase distance), and the fact that workers had to climb up and down repeatedly. (c) The daily food requirement of 14 metric tons (about 14,500 kg) for 20,000 workers represents a massive logistical challenge. This quantity of food had to be grown, transported, and distributed daily, which helps explain why most of the workers were involved in support services rather than actually lifting blocks.

(a) How long can you play tennis on the 800 kJ (about 200 kcal) of energy in a candy bar? (b) Does this seem like a long time? Discuss why exercise is necessary but may not be sufficient to cause a person to lose weight.

Strategy

From Table 2, playing tennis consumes 440 W. We use $t = E/P$ to find the time.

Solution

Part (a):

Discussion

(a) You can play tennis for approximately 30 minutes on the energy from a candy bar. (b) This seems like a fairly short time for the amount of energy in a relatively small candy bar. This illustrates why exercise alone may not be sufficient for weight loss—it’s often easier to consume calories than to burn them off. For example, eating a candy bar takes minutes, but burning it off requires a half hour of vigorous tennis. Additionally, exercise increases appetite, which can lead to consuming more calories. Sustainable weight management typically requires both regular exercise AND mindful eating habits.