Any force or combination of forces can cause a centripetal or radial acceleration. Just a few examples are the tension in the rope on a tether ball, the force of Earth’s gravity on the Moon, friction between roller skates and a rink floor, a banked roadway’s force on a car, and forces on the tube of a spinning centrifuge.

Any net force causing uniform circular motion is called a centripetal force. The direction of a centripetal force is toward the center of curvature, the same as the direction of centripetal acceleration. According to Newton’s second law of motion, net force is mass times acceleration: $\vb{F}_\text{net} =m \vb{a}$. For uniform circular motion, the acceleration is the centripetal acceleration—$\vb{a}=\vb{a}_\text{c}$. Thus, the magnitude of centripetal force$\mag{F\_\text{c} }$is

By using the expressions for the magnitude of the centripetal acceleration $\mag{ \ac }$ from $\ac=\frac{v^{2}}{r}; \ac =r \omega^{2}$, we get two expressions for the magnitude of the centripetal force $\mag{F\_\text{c}}$ in terms of mass, velocity, angular velocity, and radius of curvature:

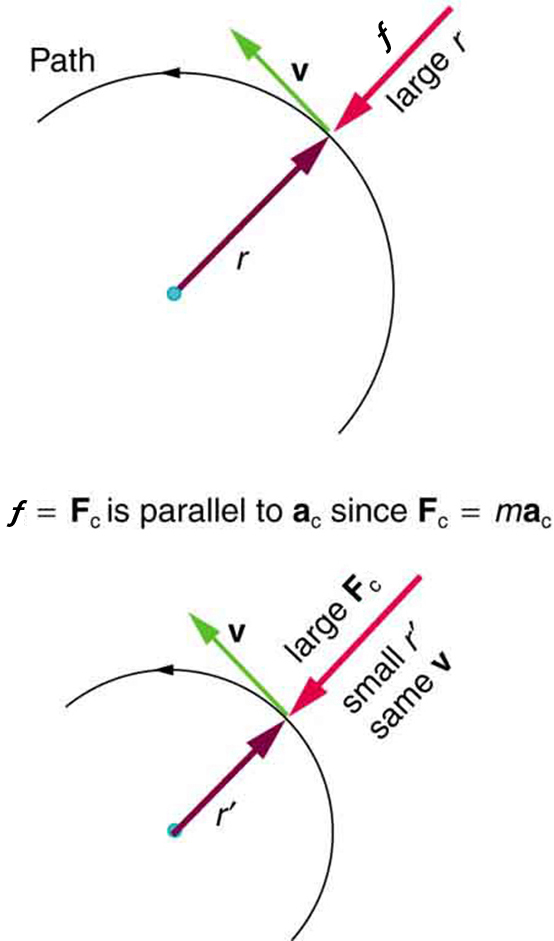

You may use whichever expression for centripetal force is more convenient. Centripetal force$\vb{F}_{\text{c}}$is always perpendicular to the path and pointing to the center of curvature, because$\vb{a}_{\text{c}}$is perpendicular to the velocity and pointing to the center of curvature.

Note that if you solve the first expression for$r$, you get

This implies that for a given mass and velocity, a large centripetal force causes a small radius of curvature—that is, a tight curve.

(a) Calculate the centripetal force exerted on a 900 kg car that negotiates a 500 m radius curve at 25.0 m/s.

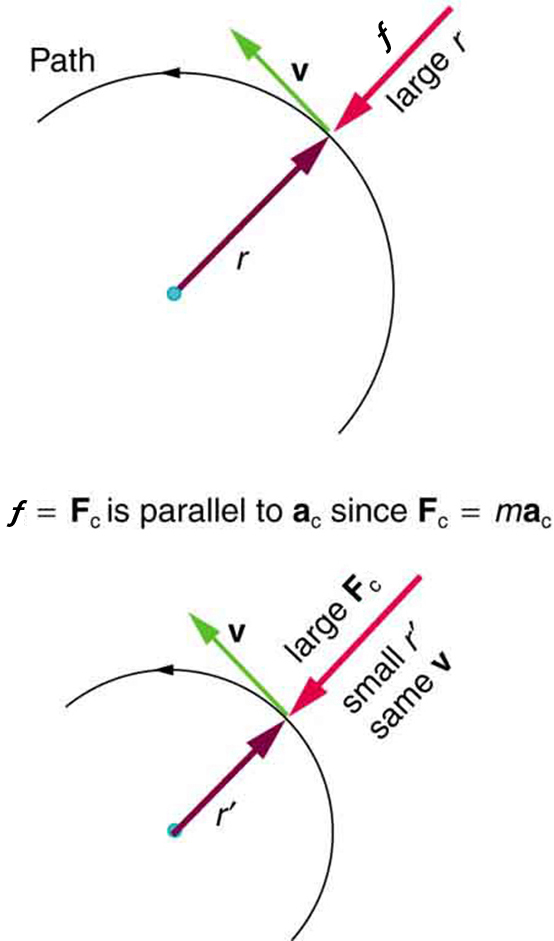

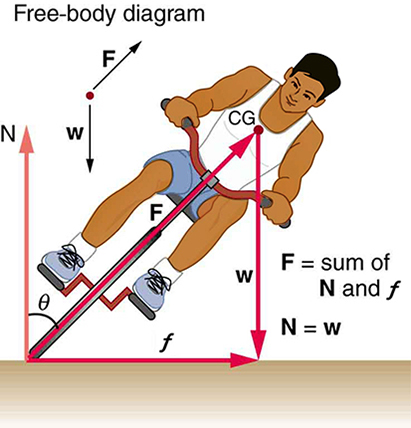

(b) Assuming an unbanked curve, find the minimum static coefficient of friction, between the tires and the road, static friction being the reason that keeps the car from slipping (see Figure 2).

Strategy and Solution for (a)

We know that $F\_{\text{c}}=\frac{ m v^{2} }{r}$. Thus,

Strategy for (b)

Figure 2 shows the forces acting on the car on an unbanked (level ground) curve. Friction is to the left, keeping the car from slipping, and because it is the only horizontal force acting on the car, the friction is the centripetal force in this case. We know that the maximum static friction (at which the tires roll but do not slip) is$\mu_{\s}N$, where$\mu_{\s}$ is the static coefficient of friction and N is the normal force. The normal force equals the car’s weight on level ground, so that$N=mg$. Thus the centripetal force in this situation is

Now we have a relationship between centripetal force and the coefficient of friction. Using the first expression for $F_{\text{c}}$ from the equation

We solve this for $\mu\_{\s}$, noting that mass cancels, and obtain

Solution for (b)

Substituting the knowns,

(Because coefficients of friction are approximate, the answer is given to only two digits.)

Discussion

We could also solve part (a) using the first expression in$\left. \begin{array}{lll} F_{\text{c}}&=&m\frac{ v^{2}}{r}\\ F_{\text{c}}&=&mr\omega^{2} \end{array} \right\} ,$because$m$,$v$, and $r$are given. The coefficient of friction found in part (b) is much smaller than is typically found between tires and roads. The car will still negotiate the curve if the coefficient is greater than 0.13, because static friction is a responsive force, being able to assume a value less than but no more than$\mu_{\s} N$. A higher coefficient would also allow the car to negotiate the curve at a higher speed, but if the coefficient of friction is less, the safe speed would be less than 25 m/s. Note that mass cancels, implying that in this example, it does not matter how heavily loaded the car is to negotiate the turn. Mass cancels because friction is assumed proportional to the normal force, which in turn is proportional to mass. If the surface of the road were banked, the normal force would be less as will be discussed below.

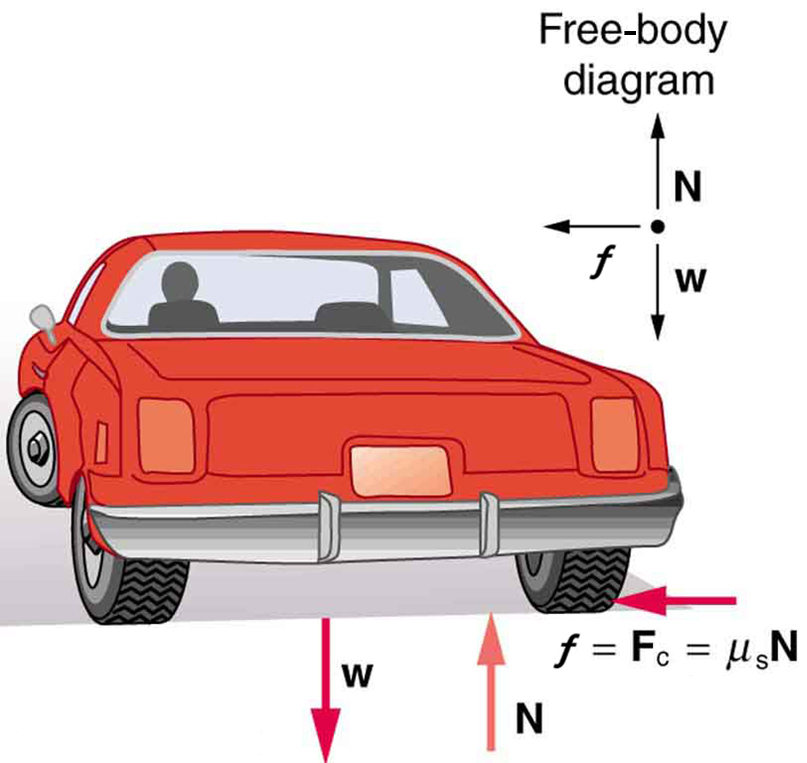

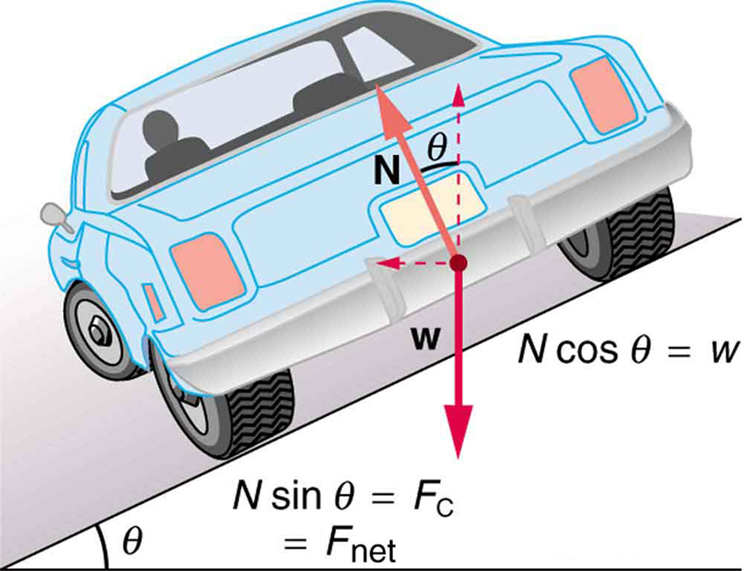

Let us now consider banked curves, where the slope of the road helps you negotiate the curve. See Figure 3. The greater the angle$\theta$, the faster you can take the curve. Race tracks for bikes as well as cars, for example, often have steeply banked curves. In an “ideally banked curve,” the angle$\theta$is such that you can negotiate the curve at a certain speed without the aid of friction between the tires and the road. We will derive an expression for$\theta$for an ideally banked curve and consider an example related to it.

For ideal banking, the net external force equals the horizontal centripetal force in the absence of friction. The components of the normal force N in the horizontal and vertical directions must equal the centripetal force and the weight of the car, respectively. In cases in which forces are not parallel, it is most convenient to consider components along perpendicular axes—in this case, the vertical and horizontal directions.

Figure 3 shows a free body diagram for a car on a frictionless banked curve. If the angle$\theta$is ideal for the speed and radius, then the net external force will equal the necessary centripetal force. The only two external forces acting on the car are its weight$\vb{w}$and the normal force of the road$\vb{N}$. (A frictionless surface can only exert a force perpendicular to the surface—that is, a normal force.) These two forces must add to give a net external force that is horizontal toward the center of curvature and has magnitude$m \frac{v^{2}}{r}$. Because this is the crucial force and it is horizontal, we use a coordinate system with vertical and horizontal axes. Only the normal force has a horizontal component, and so this must equal the centripetal force—that is,

Because the car does not leave the surface of the road, the net vertical force must be zero, meaning that the vertical components of the two external forces must be equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. From the figure, we see that the vertical component of the normal force is$N\cos{\theta}$, and the only other vertical force is the car’s weight. These must be equal in magnitude; thus,

Now we can combine the last two equations to eliminate$N$and get an expression for$\theta$, as desired. Solving the second equation for$N=mg/\left( \cos{\theta} \right)$, and substituting this into the first yields

Taking the inverse tangent gives

This expression can be understood by considering how$\theta$depends on $v$and$r$. A large$\theta$will be obtained for a large$v$and a small$r$. That is, roads must be steeply banked for high speeds and sharp curves. Friction helps, because it allows you to take the curve at greater or lower speed than if the curve is frictionless. Note that$\theta$does not depend on the mass of the vehicle.

Curves on some test tracks and race courses, such as the Daytona International Speedway in Florida, are very steeply banked. This banking, with the aid of tire friction and very stable car configurations, allows the curves to be taken at very high speed. To illustrate, calculate the speed at which a 100 m radius curve banked at 65.0° should be driven if the road is frictionless.

Strategy

We first note that all terms in the expression for the ideal angle of a banked curve except for speed are known; thus, we need only rearrange it so that speed appears on the left-hand side and then substitute known quantities.

Solution

Starting with

we get

Noting that$\tan{65.0^\circ } = 2.14$, we obtain

Discussion

This is just about 165 km/h, consistent with a very steeply banked and rather sharp curve. Tire friction enables a vehicle to take the curve at significantly higher speeds.

Calculations similar to those in the preceding examples can be performed for a host of interesting situations in which centripetal force is involved—a number of these are presented in this chapter’s Problems and Exercises.

Ask a friend or relative to swing a golf club or a tennis racquet. Take appropriate measurements to estimate the centripetal acceleration of the end of the club or racquet. You may choose to do this in slow motion.

Centripetal force$\vb{F}\_\text{c}$is any force causing uniform circular motion. It is a “center-seeking” force that always points toward the center of rotation. It is perpendicular to linear velocity$v$and has magnitude

which can also be expressed as

If you wish to reduce the stress (which is related to centripetal force) on high-speed tires, would you use large- or small-diameter tires? Explain.

Define centripetal force. Can any type of force (for example, tension, gravitational force, friction, and so on) be a centripetal force? Can any combination of forces be a centripetal force?

If centripetal force is directed toward the center, why do you feel that you are ‘thrown’ away from the center as a car goes around a curve? Explain.

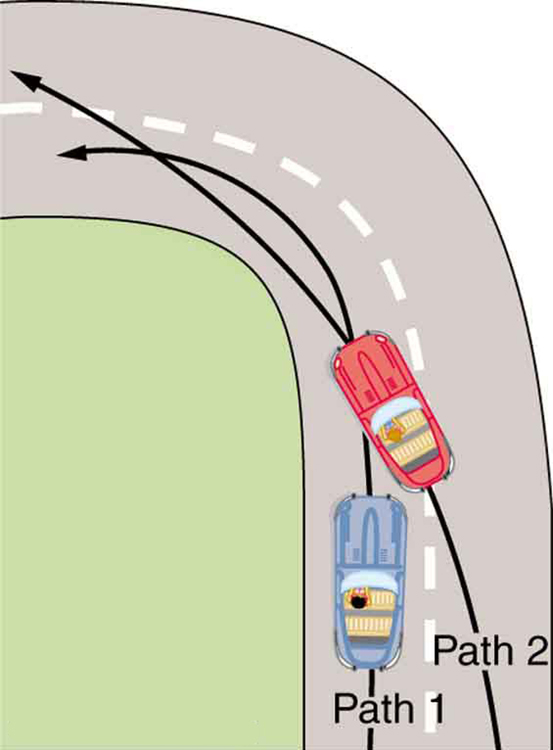

Race car drivers routinely cut corners as shown in Figure 4. Explain how this allows the curve to be taken at the greatest speed.

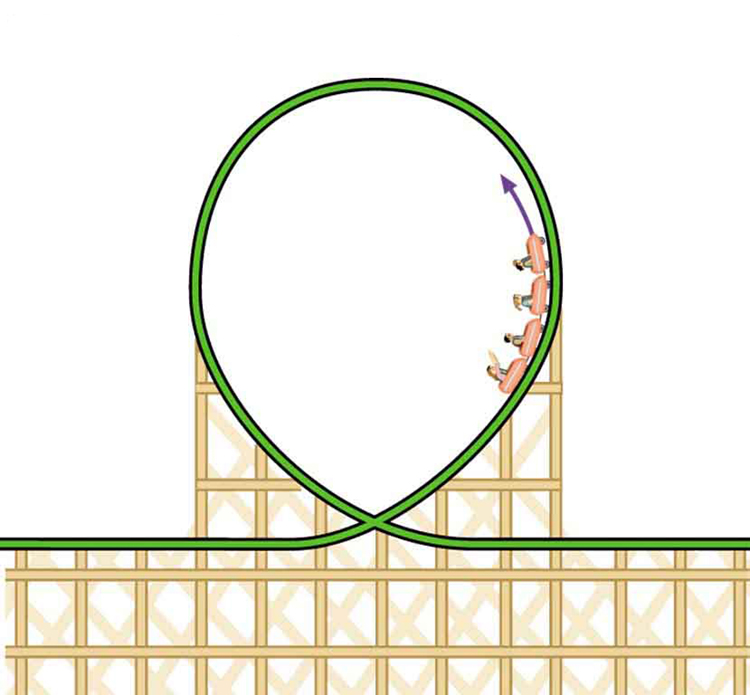

A number of amusement parks have rides that make vertical loops like the one shown in Figure 5. For safety, the cars are attached to the rails in such a way that they cannot fall off. If the car goes over the top at just the right speed, gravity alone will supply the centripetal force. What other force acts and what is its direction if:

(a) The car goes over the top at faster than this speed?

(b)The car goes over the top at slower than this speed?

What is the direction of the force exerted by the car on the passenger as the car goes over the top of the amusement ride pictured in Figure 5 under the following circumstances:

(a) The car goes over the top at such a speed that the gravitational force is the only force acting?

(b) The car goes over the top faster than this speed?

(c) The car goes over the top slower than this speed?

As a skater forms a circle, what force is responsible for making her turn? Use a free body diagram in your answer.

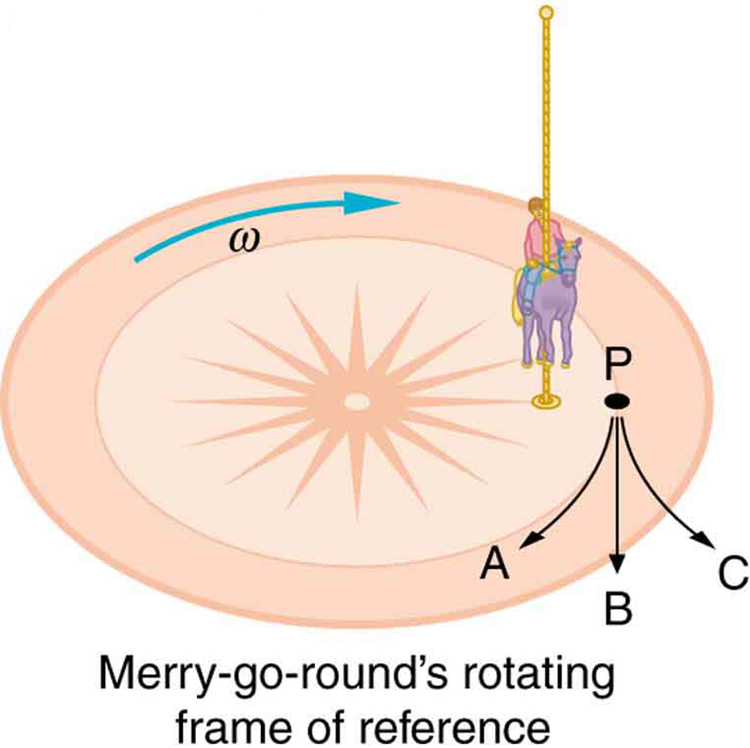

Suppose a child is riding on a merry-go-round at a distance about halfway between its center and edge. She has a lunch box resting on wax paper, so that there is very little friction between it and the merry-go-round. Which path shown in Figure 6 will the lunch box take when she lets go? The lunch box leaves a trail in the dust on the merry-go-round. Is that trail straight, curved to the left, or curved to the right? Explain your answer.

Do you feel yourself thrown to either side when you negotiate a curve that is ideally banked for your car’s speed? What is the direction of the force exerted on you by the car seat?

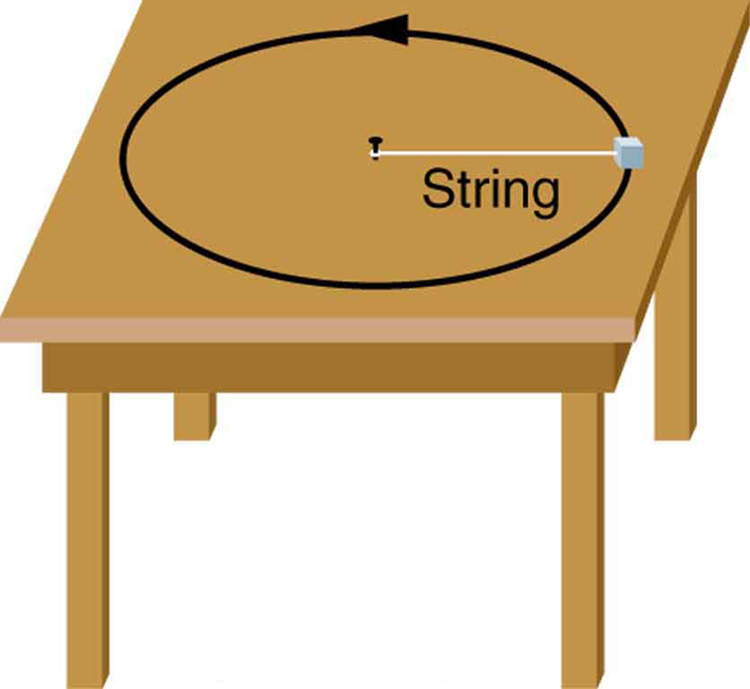

Suppose a mass is moving in a circular path on a frictionless table as shown in figure. In the Earth’s frame of reference, there is no centrifugal force pulling the mass away from the centre of rotation, yet there is a very real force stretching the string attaching the mass to the nail. Using concepts related to centripetal force and Newton’s third law, explain what force stretches the string, identifying its physical origin.

(a) A 22.0 kg child is riding a playground merry-go-round that is rotating at 40.0 rev/min. What centripetal force must she exert to stay on if she is 1.25 m from its center?

(b) What centripetal force does she need to stay on an amusement park merry-go-round that rotates at 3.00 rev/min if she is 8.00 m from its center?

(c) Compare each force with her weight.

Strategy

We’ll convert angular velocities to rad/s, then use$F_c = mr\omega^2$to calculate the centripetal force. We’ll compare each to the child’s weight$w = mg$.

Solution

(a) Convert angular velocity and calculate centripetal force:

(b) For the amusement park ride:

(c) Calculate the child’s weight and compare:

Discussion

On the playground merry-go-round, the child must exert a centripetal force of 483 N, which is 2.24 times her weight - she would feel significantly “heavier” and need to hold on tightly. On the slower amusement park ride, she needs only 17.4 N, which is just 0.0807 times her weight - barely noticeable. The much larger radius partially compensates for the slower rotation rate in the second case.

Calculate the centripetal force on the end of a 100 m (radius) wind turbine blade that is rotating at 0.5 rev/s. Assume the mass is 4 kg.

Strategy

We need to find the centripetal force using$F_c = mr\omega^2$. First, we’ll convert the angular velocity from rev/s to rad/s, then calculate the centripetal force.

Solution

Convert angular velocity to rad/s:

Calculate the centripetal force:

Discussion

The centripetal force on the end of the wind turbine blade is approximately 3950 N or about 3.95 kN. This substantial force must be withstood by the blade structure and mounting points, which is why wind turbine blades are constructed from strong, lightweight composite materials. Even though the mass at the tip is only 4 kg, the large radius and rotational speed create a significant centripetal force.

What is the ideal banking angle for a gentle turn of 1.20 km radius on a highway with a 105 km/h speed limit (about 65 mi/h), assuming everyone travels at the limit?

Strategy

For an ideally banked curve, we use$\theta = \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{v^2}{rg}\right)$. We’ll need to convert the speed from km/h to m/s.

Solution

Convert the speed to m/s:

Convert the radius to meters:

Calculate the ideal banking angle:

Discussion

The ideal banking angle for this highway curve is 4.14°, which is a very gentle slope. At this angle, cars traveling at exactly 105 km/h would not need any friction between the tires and road to negotiate the turn - the normal force from the banked road would provide exactly the right amount of centripetal force. In practice, highway curves are typically banked at conservative angles to accommodate a range of speeds safely.

What is the ideal speed to take a 100 m radius curve banked at a 20.0° angle?

Strategy

For an ideally banked curve (no friction needed), we use the relationship$\tan\theta = \frac{v^2}{rg}$. We’ll solve for$v$and substitute the known values.

Solution

Starting with the ideal banking equation:

Solve for$v$:

Substitute known values ($r = 100$m,$g = 9.80$m/s²,$\theta = 20.0°$):

Discussion

The ideal speed to take the 100 m radius curve banked at 20.0° is 18.9 m/s (about 68 km/h or 42 mi/h). At this speed, no friction between the tires and road is needed to maintain the circular path - the normal force from the banked road provides exactly the right amount of centripetal force. At speeds higher or lower than this ideal speed, friction would be required to prevent the car from sliding up or down the banked surface.

(a) What is the radius of a bobsled turn banked at 75.0° and taken at 30.0 m/s, assuming it is ideally banked?

(b) Calculate the centripetal acceleration.

(c) Does this acceleration seem large to you?

Strategy

For an ideally banked curve (no friction required), we use the relationship$\tan\theta = \frac{v^2}{rg}$. We’ll solve for the radius$r$, then calculate the centripetal acceleration using$a_c = \frac{v^2}{r}$and compare it to$g$.

Solution

Given:

(a) Radius of the turn:

From the ideal banking formula:

Solving for$r$:

Substitute values:

(b) Centripetal acceleration:

(c) Comparison to g:

So$a_c = 3.73g$.

Discussion

The centripetal acceleration of 3.73g means that the bobsledders experience a force nearly 4 times their normal weight pushing them into the side of the bobsled. While this might not seem extreme compared to fighter pilots who experience up to 9g, bobsledders must maintain this level of force throughout the turn while also controlling their sled. The 75° banking angle is quite steep - nearly vertical - which is typical for bobsled tracks where tight, fast turns are needed. The small radius of just 24.6 m allows for exciting, high-speed turns while the steep banking keeps the forces manageable. Bobsledders train to handle these forces and must have strong core and neck muscles to maintain proper positioning throughout the run.

Answer

(a) The radius of the bobsled turn is 24.6 m.

(b) The centripetal acceleration is 36.6 m/s².

(c) This acceleration is 3.73g, which is significant but typical for bobsled runs. It requires athletic conditioning but is within human tolerance for short durations.

Part of riding a bicycle involves leaning at the correct angle when making a turn, as seen in Figure 8. To be stable, the force exerted by the ground must be on a line going through the center of gravity. The force on the bicycle wheel can be resolved into two perpendicular components—friction parallel to the road (this must supply the centripetal force), and the vertical normal force (which must equal the system’s weight).

(a) Show that$\theta$ (as defined in the figure) is related to the speed$v$and radius of curvature$r$of the turn in the same way as for an ideally banked roadway—that is,$\theta ={\tan}^{-1}{v}^{2}/rg$ (b) Calculate$\theta$for a 12.0 m/s turn of radius 30.0 m (as in a race).

Strategy

(a) We’ll analyze the forces on the bicycle and rider system. The net force from the ground has components: horizontal (friction providing centripetal force) and vertical (normal force balancing weight). The resultant must pass through the center of gravity, making angle$\theta$with the vertical. (b) We’ll use the derived formula to calculate the angle for the given speed and radius.

Solution

(a) The horizontal component of the ground force is the friction$f$, which provides the centripetal force:

The vertical component is the normal force$N$, which equals the weight:

The angle$\theta$that the resultant force makes with the vertical is:

Therefore:

This is identical to the formula for an ideally banked curve.

(b) Calculate$\theta$for$v = 12.0$m/s and$r = 30.0$m:

Discussion

We have shown that the bicycle lean angle follows the same relationship as an ideally banked curve. For the racing turn at 12.0 m/s with a 30.0 m radius, the cyclist must lean at 26.1° from the vertical. This significant lean angle is necessary to keep the line of action of the ground force passing through the center of gravity, ensuring stability. Experienced cyclists make these adjustments instinctively.

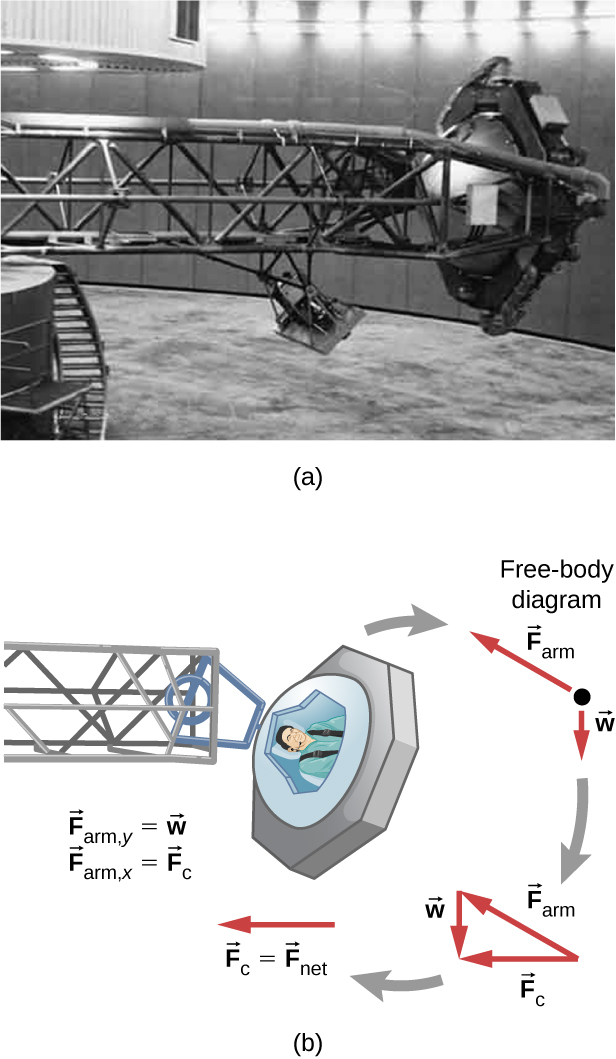

A large centrifuge, like the one shown in Figure 9(a), is used to expose aspiring astronauts to accelerations similar to those experienced in rocket launches and atmospheric reentries.

(a) At what angular velocity is the centripetal acceleration$10 g$if the rider is 15.0 m from the center of rotation?

(b) The rider’s cage hangs on a pivot at the end of the arm, allowing it to swing outward during rotation as shown in Figure 9(b). At what angle$\theta$below the horizontal will the cage hang when the centripetal acceleration is$10 g$? (Hint: The arm supplies centripetal force and supports the weight of the cage. Draw a free body diagram of the forces to see what the angle$\theta$should be.)

Strategy

(a) We’ll use$a_c = r\omega^2$with$a_c = 10g = 98.0$m/s² and solve for$\omega$. (b) We’ll draw a free body diagram and use the fact that the cage hangs at an angle where the arm force can simultaneously provide the centripetal force and support the weight. Using geometry,$\tan\theta = \frac{g}{a_c}$.

Solution

(a) Using$a_c = r\omega^2$, solve for$\omega$:

(b) Draw a free body diagram: The cage experiences its weight$mg$downward and the arm force$F$at angle$\theta$below horizontal. The horizontal component of$F$provides centripetal force, while the vertical component balances weight:

Dividing the second equation by the first:

Discussion

The centrifuge must rotate at 2.56 rad/s (about 24.4 rpm) to produce 10g acceleration at a radius of 15.0 m. The cage hangs only 5.71° below horizontal because the centripetal acceleration (10g) is much larger than gravitational acceleration (1g). This small angle means the arm force is nearly horizontal, pointing mostly toward the center to provide the large centripetal force needed. As rotation increases, the angle becomes even smaller, approaching horizontal. This pivoting cage design ensures the rider always experiences force along the cage axis, preventing uncomfortable sideways forces.

Integrated Concepts

If a car takes a banked curve at less than the ideal speed, friction is needed to keep it from sliding toward the inside of the curve (a real problem on icy mountain roads). (a) Calculate the ideal speed to take a 100 m radius curve banked at $15.0^\circ$. (b) What is the minimum coefficient of friction needed for a frightened driver to take the same curve at 20.0 km/h?

Strategy

(a) For the ideal speed (no friction needed), the horizontal component of the normal force provides exactly the needed centripetal force. We’ll use$v = \sqrt{rg\tan\theta}$. (b) At a speed lower than ideal, friction must prevent sliding inward. We’ll analyze forces to find the minimum coefficient of friction.

Solution

(a) Calculate the ideal speed using the formula for a banked curve:

(b) Convert the actual speed to m/s:

At this slower speed, the car tends to slide down the bank. The required centripetal force is less than what the banked curve would naturally provide, so friction must act up the slope. Using force balance equations for a banked curve with friction:

Calculate$\frac{v^2}{rg}$:

Now calculate$\mu_s$:

Discussion

The ideal speed for this banked curve is 16.2 m/s (about 58 km/h), at which no friction is needed. However, at the much slower speed of 20.0 km/h (5.56 m/s), the car requires a minimum coefficient of friction of 0.234 to prevent sliding down toward the inside of the curve. This is why icy mountain roads with banked curves are particularly dangerous—if the coefficient of friction drops below this value due to ice, slow-moving vehicles will slide inward regardless of driver skill. The problem illustrates why banked curves are designed for a specific “ideal” speed, and driving significantly slower than this speed can be just as problematic as driving too fast.

Modern roller coasters have vertical loops like the one shown in Figure 10. The radius of curvature is smaller at the top than on the sides so that the downward centripetal acceleration at the top will be greater than the acceleration due to gravity, keeping the passengers pressed firmly into their seats. What is the speed of the roller coaster at the top of the loop if the radius of curvature there is 15.0 m and the downward acceleration of the car is 1.50 g?

Strategy

We need to find the speed at the top of the loop given the centripetal acceleration and radius of curvature. We’ll use$a_c = \frac{v^2}{r}$and solve for$v$. The centripetal acceleration is given as 1.50g, where$g = 9.80$m/s².

Solution

The centripetal acceleration is:

Using the centripetal acceleration formula and solving for$v$:

Discussion

The speed of the roller coaster at the top of the loop is 14.9 m/s (about 54 km/h or 33 mi/h). At this speed with a 15.0 m radius of curvature, the centripetal acceleration is 1.50g, which means passengers experience a downward force 1.50 times their normal weight. This keeps them firmly pressed into their seats even though they are upside down at the top of the loop, creating the thrilling sensation that makes roller coasters exciting while maintaining safety.

Unreasonable Results

(a) Calculate the minimum coefficient of friction needed for a car to negotiate an unbanked 50.0 m radius curve at 30.0 m/s.

(b) What is unreasonable about the result?

(c) Which premises are unreasonable or inconsistent?

Strategy

For an unbanked curve, friction provides the centripetal force. We’ll set up the equation where friction equals the required centripetal force, then solve for the coefficient of friction. We’ll then analyze whether the result is physically reasonable.

Solution

(a) For circular motion on an unbanked curve:

The centripetal force is provided by friction:

This must equal the required centripetal force:

Solving for the coefficient of friction (mass cancels):

(b) A coefficient of friction of 1.84 is unreasonable. Typical coefficients of static friction between rubber tires and dry pavement range from 0.7 to 1.0. Values significantly greater than 1.0 are not physically achievable with normal road surfaces and tires.

(c) The assumed speed of 30.0 m/s (108 km/h or 67 mph) is too great for a 50.0 m radius curve. At this tight radius, safer speeds would be around 15-20 m/s. Alternatively, banking the curve would reduce the required friction coefficient.

Discussion

This problem illustrates why highway curves are designed with specific speed limits based on their radius. For a 50.0 m radius curve with μ = 0.7 (wet conditions), the maximum safe speed would be: $v = \sqrt{\mu rg} = \sqrt{(0.7)(50.0)(9.80)} = 18.5 \text{ m/s} \approx 67 \text{ km/h}$

This is why tight curves on roads have reduced speed limits and are often banked.