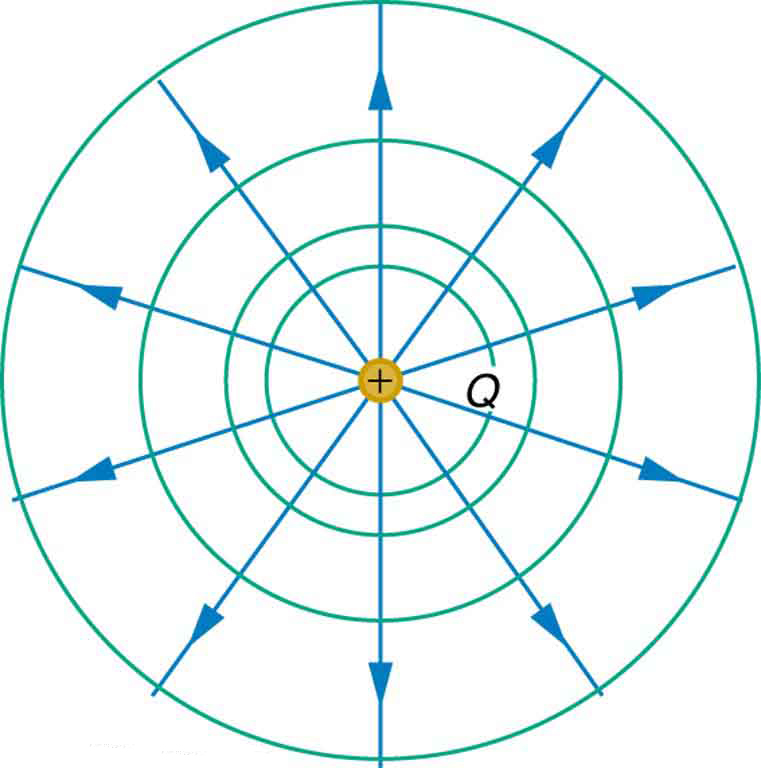

We can represent electric potentials (voltages) pictorially, just as we drew pictures to illustrate electric fields. Of course, the two are related. Consider [Figure 1], which shows an isolated positive point charge and its electric field lines. Electric field lines radiate out from a positive charge and terminate on negative charges. While we use blue arrows to represent the magnitude and direction of the electric field, we use green lines to represent places where the electric potential is constant. These are called equipotential lines in two dimensions, or equipotential surfaces in three dimensions. The term equipotential is also used as a noun, referring to an equipotential line or surface. The potential for a point charge is the same anywhere on an imaginary sphere of radius $r$ surrounding the charge. This is true since the potential for a point charge is given by $V=kQ/r$ and, thus, has the same value at any point that is a given distance $r$ from the charge. An equipotential sphere is a circle in the two-dimensional view of [Figure 1]. Since the electric field lines point radially away from the charge, they are perpendicular to the equipotential lines.

It is important to note that equipotential lines are always perpendicular to electric field lines . No work is required to move a charge along an equipotential, since $\Delta V=0$ . Thus the work is

Work is zero if force is perpendicular to motion. Force is in the same direction as $\vb{E}$ , so that motion along an equipotential must be perpendicular to $\vb{E}$ . More precisely, work is related to the electric field by

Note that in the above equation, $E$ and $F$ symbolize the magnitudes of the electric field strength and force, respectively. Neither $q$ nor $\vb{E}$ nor $d$ is zero, and so $\cos \theta$ must be 0, meaning $\theta$ must be $90 ^\circ$ . In other words, motion along an equipotential is perpendicular to $\vb{E}$.

One of the rules for static electric fields and conductors is that the electric field must be perpendicular to the surface of any conductor. This implies that a conductor is an equipotential surface in static situations . There can be no voltage difference across the surface of a conductor, or charges will flow. One of the uses of this fact is that a conductor can be fixed at zero volts by connecting it to the earth with a good conductor—a process called grounding. Grounding can be a useful safety tool. For example, grounding the metal case of an electrical appliance ensures that it is at zero volts relative to the earth.

A conductor can be fixed at zero volts by connecting it to the earth with a good conductor—a process called grounding.

Because a conductor is an equipotential, it can replace any equipotential surface. For example, in [Figure 1] a charged spherical conductor can replace the point charge, and the electric field and potential surfaces outside of it will be unchanged, confirming the contention that a spherical charge distribution is equivalent to a point charge at its center.

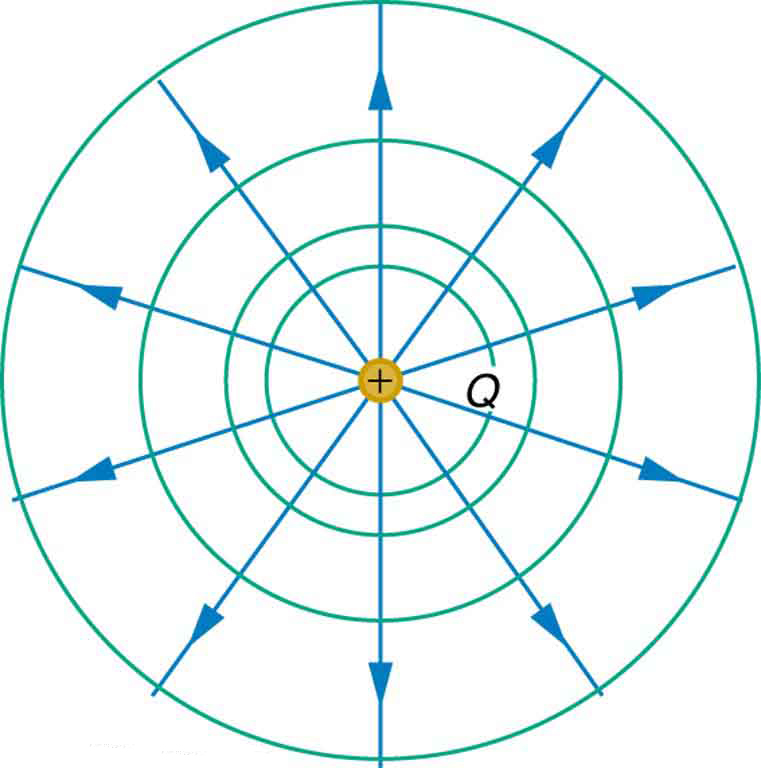

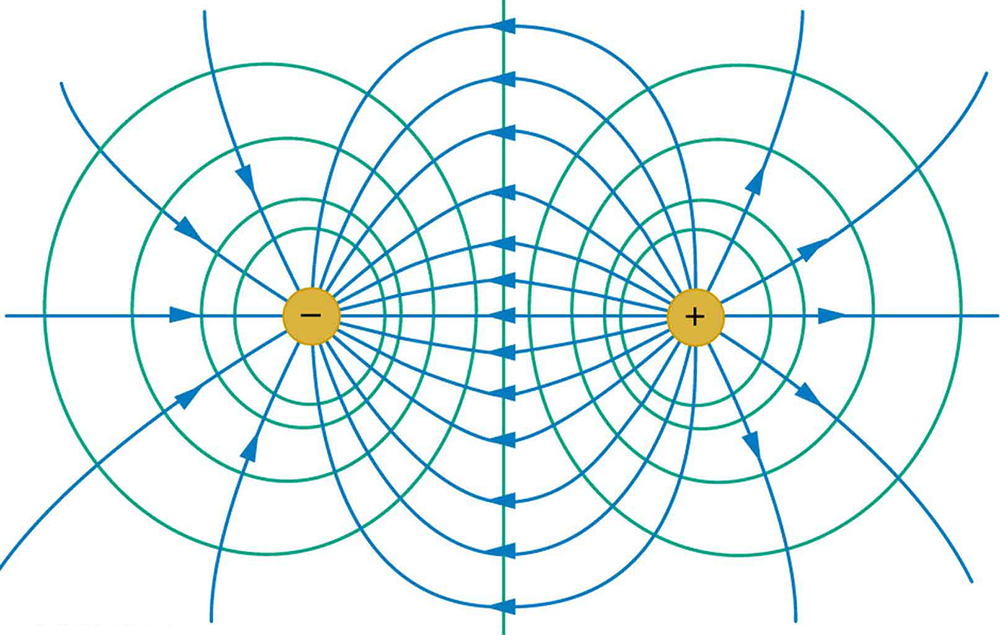

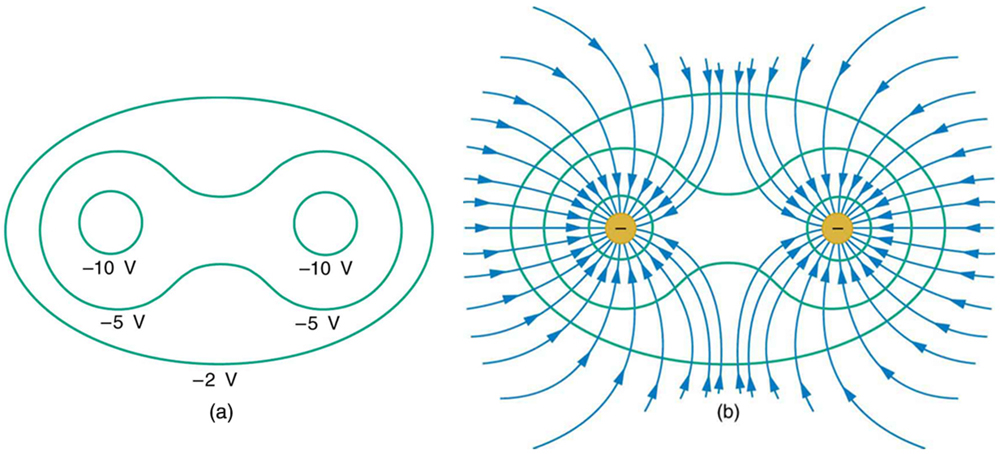

[Figure 2] shows the electric field and equipotential lines for two equal and opposite charges. Given the electric field lines, the equipotential lines can be drawn simply by making them perpendicular to the electric field lines. Conversely, given the equipotential lines, as in [Figure 3]( a), the electric field lines can be drawn by making them perpendicular to the equipotentials, as in [Figure 3](b).

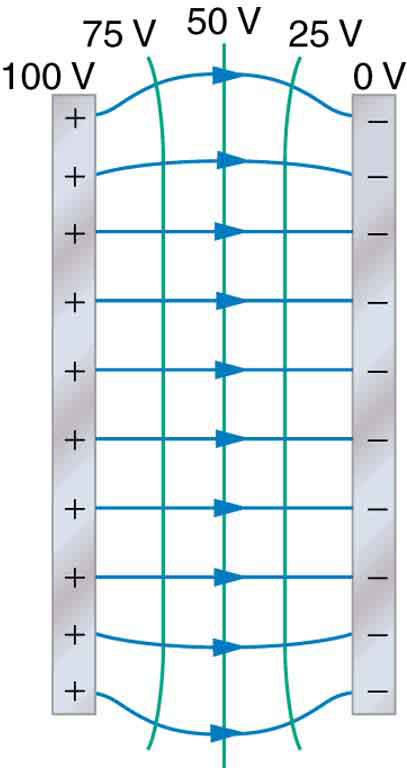

One of the most important cases is that of the familiar parallel conducting plates shown in [Figure 4]. Between the plates, the equipotentials are evenly spaced and parallel. The same field could be maintained by placing conducting plates at the equipotential lines at the potentials shown.

An important application of electric fields and equipotential lines involves the heart. The heart relies on electrical signals to maintain its rhythm. The movement of electrical signals causes the chambers of the heart to contract and relax. When a person has a heart attack, the movement of these electrical signals may be disturbed. An artificial pacemaker and a defibrillator can be used to initiate the rhythm of electrical signals. The equipotential lines around the heart, the thoracic region, and the axis of the heart are useful ways of monitoring the structure and functions of the heart. An electrocardiogram ( ECG) measures the small electric signals being generated during the activity of the heart. More about the relationship between electric fields and the heart is discussed in Energy Stored in Capacitors.

Move point charges around on the playing field and then view the electric field, voltages, equipotential lines, and more. It's colorful, it's dynamic, it's free.

What is an equipotential line? What is an equipotential surface?

Explain in your own words why equipotential lines and surfaces must be perpendicular to electric field lines.

Can different equipotential lines cross? Explain.

(a) Sketch the equipotential lines near a point charge $+q$ . Indicate the direction of increasing potential. (b) Do the same for a point charge $-3 \text{q}$.

Strategy

Equipotential lines for a point charge are concentric circles (spheres in 3D) centered on the charge. The potential from a point charge is $V = kQ/r$, so all points at the same distance have the same potential.

Solution

(a) For charge +q:

The equipotential lines are concentric circles centered on the positive charge. Since $V = kq/r$:

(b) For charge -3q:

The equipotential lines are also concentric circles, but:

Discussion

The key difference is the direction of increasing potential: toward a positive charge, away from a negative charge. This is consistent with the fact that positive charges create positive potentials and negative charges create negative potentials. The spacing of equipotential lines indicates the strength of the electric field—closer spacing means stronger field.

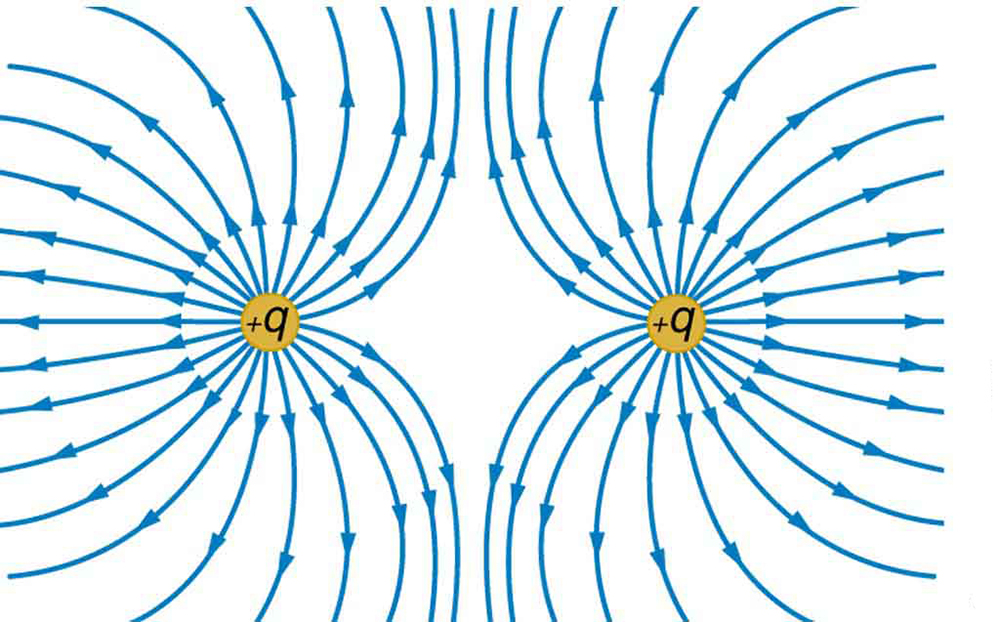

Sketch the equipotential lines for the two equal positive charges shown in [Figure 5]. Indicate the direction of increasing potential.

Strategy

Equipotential lines must be perpendicular to electric field lines at every point. For two equal positive charges, we use the principle that the electric potential from multiple charges adds algebraically: $V = V_1 + V_2$. Near each charge, equipotentials are nearly circular; far away, they become circular (like a single charge of +2q); in between, they have more complex shapes determined by the requirement of perpendicularity to field lines.

Solution

The equipotential lines must be perpendicular to the electric field lines at every point.

Description of the sketch:

Near each charge: The equipotential lines are nearly circular, centered on each charge individually.

In the region between the charges: The equipotential lines curve around both charges. At the exact midpoint between the charges, there is a saddle point where the equipotential line is a straight line perpendicular to the line connecting the charges.

Far from both charges: The equipotential lines become approximately circular, centered on the midpoint between the charges (the system looks like a single charge of +2q from far away).

Direction of increasing potential: Arrows point toward either charge. The highest potential regions are closest to either positive charge.

Between the charges: The potential is higher than at infinity but lower than very close to either charge. There is no equipotential line that passes between the charges without encircling one or both.

Discussion

The equipotential lines form closed curves that must either encircle one charge or both charges. Since both charges are positive, the potential is positive everywhere and increases as you approach either charge.

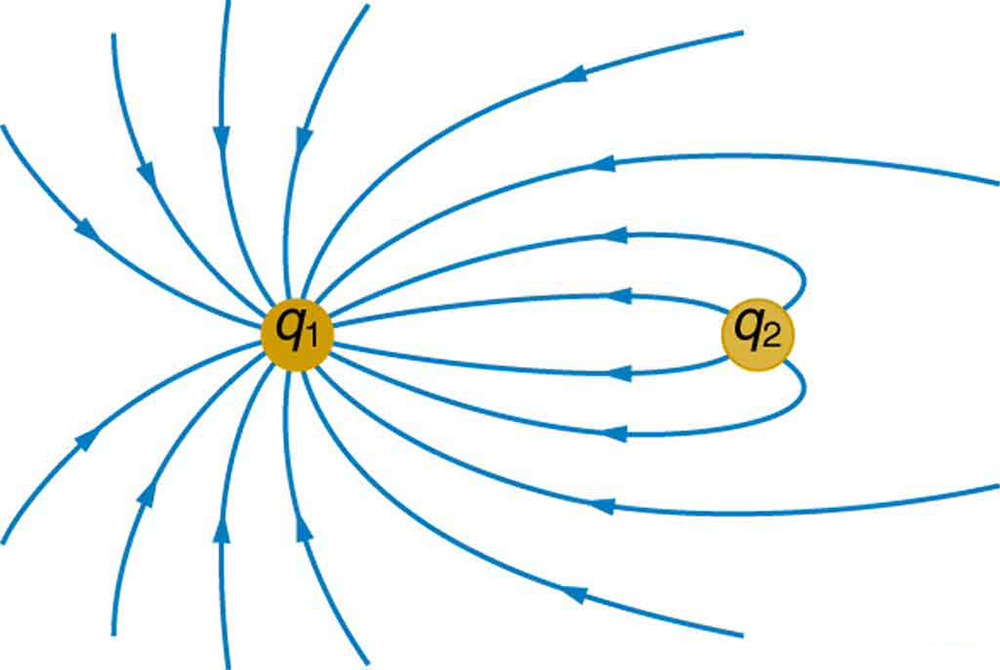

[Figure 6] shows the electric field lines near two charges ${q}_{1}$ and ${q}_{2}$ , the first having a magnitude four times that of the second. Sketch the equipotential lines for these two charges, and indicate the direction of increasing potential.

Strategy

First, interpret the electric field lines in the figure to determine the signs and relative magnitudes of the charges. Field lines point away from positive charges and toward negative charges. Once we know the charge configuration, we sketch equipotentials perpendicular to the field lines, noting that potential increases toward positive charges and away from negative charges. The asymmetry in charge magnitudes will create asymmetric equipotential patterns.

Solution

| From the figure, $q_1$ is negative (field lines point toward it) and $q_2$ is positive (field lines point away), with $$ | q_1 | = 4 | q_2 | $$. |

Description of the sketch:

Near $q_1$ (negative, larger): Equipotential lines are nearly circular and closely spaced due to the larger charge magnitude. Potential is strongly negative near this charge.

Near $q_2$ (positive, smaller): Equipotential lines are nearly circular but more widely spaced. Potential is positive but smaller in magnitude.

Between the charges: Some equipotential lines connect the two charges (for the zero and small positive/negative potentials). There is a point where $V = 0$ along the line connecting the charges, closer to the smaller charge.

Direction of increasing potential: Arrows point away from $q_1$ (the negative charge) and toward $q_2$ (the positive charge).

Discussion

The asymmetry in charge magnitude creates an asymmetric pattern. The equipotential lines are more densely packed around the larger negative charge, indicating a stronger field there.

Sketch the equipotential lines a long distance from the charges shown in [Figure 6]. Indicate the direction of increasing potential.

Strategy

At large distances from any charge configuration, the system appears as a single point charge with net charge $Q_{\text{net}} = q_1 + q_2$. The equipotential lines become spherical surfaces (circles in 2D) centered on the charge system. We use the far-field approximation where $V \approx kQ_{\text{net}}/r$, which produces evenly-spaced circular equipotentials for equal voltage intervals.

Solution

At large distances, any system of charges appears as a single point charge with the net charge $Q_{net} = q_1 + q_2 = -4q + q = -3q$.

Description of the sketch:

Far from both charges: The equipotential lines become nearly circular (spherical in 3D), centered approximately on the centroid of the charge distribution.

Since the net charge is negative: The potential is negative everywhere at large distances and approaches zero at infinity.

Direction of increasing potential: Arrows point outward (away from the charge system), since potential increases (becomes less negative) as distance increases.

Spacing: The lines are evenly spaced for equal voltage intervals, characteristic of the $V = kQ_{net}/r$ dependence.

Discussion

This is an example of the far-field approximation: any charge distribution looks like a point charge from sufficiently far away. The net charge determines the far-field behavior.

Sketch the equipotential lines in the vicinity of two opposite charges, where the negative charge is three times as great in magnitude as the positive. Indicate the direction of increasing potential.

Strategy

For opposite charges with $q_- = -3q$ and $q_+ = +q$, we recognize this as a dipole-like configuration. The key is finding the zero-potential surface where $V = k(q_+/r_+ - 3q/r_-) = 0$, which occurs where $r_+ = r_-/3$. Equipotentials are perpendicular to field lines, with potential increasing toward the positive charge and away from the negative charge. The net charge is $-2q$, affecting far-field behavior.

Solution

With $q_{-} = -3q$ and $q_{+} = +q$, the net charge is $-2q$.

Description of the sketch:

Near the positive charge (+q): Equipotential lines are nearly circular with positive potential values. Lines are more widely spaced (smaller charge, weaker field).

Near the negative charge (-3q): Equipotential lines are nearly circular with negative potential values. Lines are more closely spaced (larger charge, stronger field).

Between the charges: There is a point where $V = 0$, located closer to the smaller positive charge (at about 1/4 of the distance from the positive charge, since the ratio of distances must equal the ratio of charge magnitudes for $V = 0$).

Direction of increasing potential: Arrows point toward the positive charge and away from the negative charge.

Far away: Equipotential lines become circular, representing the net charge of $-2q$.

Discussion

The zero-potential surface forms a closed curve encircling the positive charge, with all points inside having positive potential and all points outside having negative potential (except very close to the positive charge).

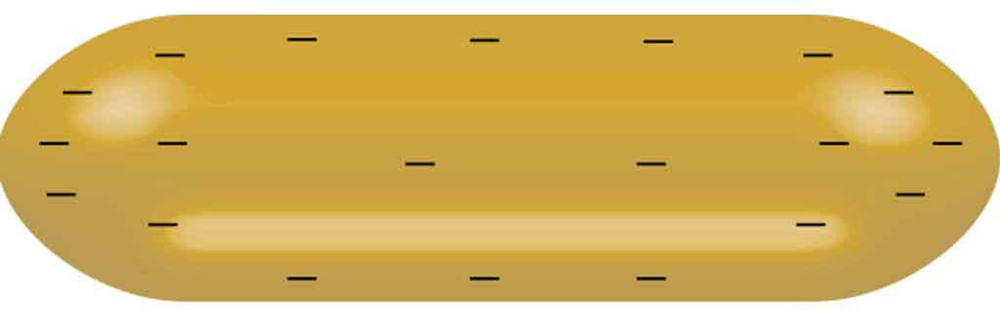

Sketch the equipotential lines in the vicinity of the negatively charged conductor in [Figure 7]. How will these equipotentials look a long distance from the object?

Strategy

Conductors in electrostatic equilibrium are equipotential surfaces—all points on and inside have the same potential. The first equipotential outside the conductor follows its shape closely. Electric field lines are perpendicular to the conductor surface, so equipotentials are also perpendicular to field lines. At large distances, the conductor appears as a point charge, making equipotentials circular.

Solution

Near the conductor:

The conductor surface itself is an equipotential surface (all conductors are equipotentials in electrostatic equilibrium).

The first equipotential line outside the conductor follows the shape of the conductor closely—it has the same oblong shape.

The charge density is higher at the more curved ends of the oblong, so the electric field is stronger there and equipotential lines are more closely spaced near the ends.

Direction of increasing potential: Since the charge is negative, potential increases as you move away from the conductor. Arrows point outward.

At large distances:

The equipotential lines become circular (spherical surfaces in 3D), centered on the object. From far away, any finite charge distribution appears as a point charge.

Discussion

The transition from conductor-shaped equipotentials near the surface to circular equipotentials far away is gradual. This is a general principle: local geometry matters near an object, but far away, only the total charge matters.

Sketch the equipotential lines surrounding the two conducting plates shown in [Figure 8], given the top plate is positive and the bottom plate has an equal amount of negative charge. Be certain to indicate the distribution of charge on the plates. Is the field strongest where the plates are closest? Why should it be?

Strategy

For parallel conducting plates, charge concentrates on facing surfaces due to attraction between opposite charges. Between the plates, the field is approximately uniform ($E = V/d$), creating parallel, evenly-spaced equipotentials. Where plates are closer, the same voltage difference exists over a smaller distance, yielding stronger field ($E = V/d$ increases as $d$ decreases) and closer equipotential spacing.

Solution

Charge distribution on plates:

The charge concentrates on the facing surfaces of the plates (the surfaces closest to each other). Additionally, charge density is higher at the edges of the plates, particularly at the corners where the curvature is greatest.

Equipotential lines:

Between the plates (close region): Equipotential lines are approximately parallel and evenly spaced, indicating a nearly uniform field. Higher potential (more positive) is near the top plate.

Near the edges: Equipotential lines curve outward, following the fringe fields.

Outside the plates: Equipotential lines curve around the plates, becoming more circular at large distances.

Is the field strongest where the plates are closest?

Yes. The field is strongest where the plates are closest because:

Same voltage difference over smaller distance: $E = V/d$, so smaller $d$ means larger $E$.

Closer equipotential lines: Where plates are closer, the same potential difference is spread over less distance, so equipotential lines are more closely spaced—indicating stronger field.

Charge concentration: Opposite charges attract, so charges migrate toward the facing surfaces, increasing the surface charge density and field there.

Discussion

This configuration is the basis of a parallel-plate capacitor. The approximately uniform field between the plates is useful for many applications. The non-uniform fringe fields at the edges are often neglected in calculations but become important in precise applications.

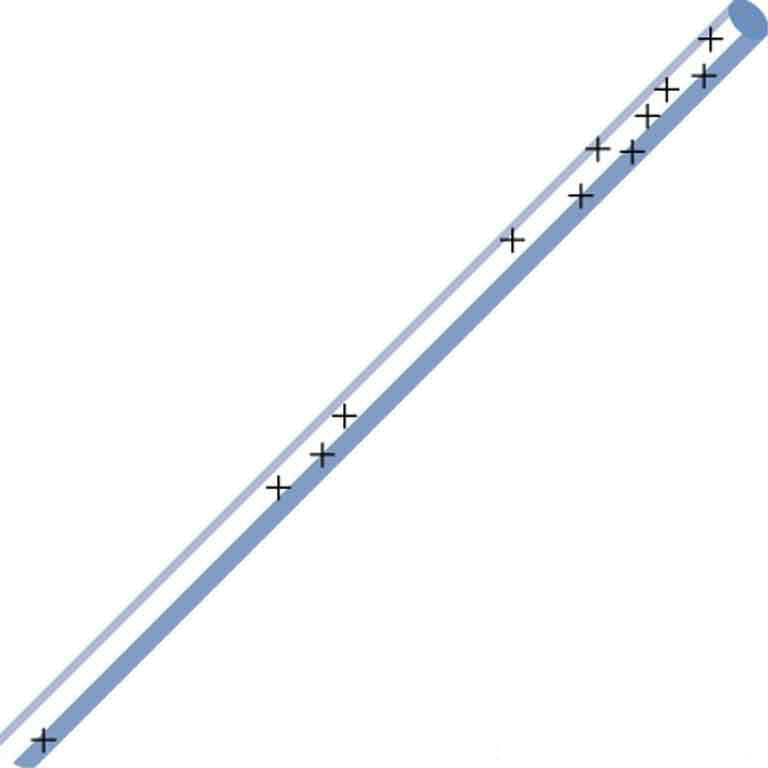

(a) Sketch the electric field lines in the vicinity of the charged insulator in [Figure 9]. Note its non-uniform charge distribution. (b) Sketch equipotential lines surrounding the insulator. Indicate the direction of increasing potential.

Strategy

Unlike conductors, insulators can maintain non-uniform charge distributions. Field line density reflects local charge density—more field lines where charge is more concentrated. Equipotentials are perpendicular to field lines everywhere. Since all charges are positive, potential increases toward the rod, with the highest values near the most heavily charged region. The non-uniform charge creates non-uniform field strength and equipotential spacing.

Solution

(a) Electric field lines:

The electric field lines radiate outward from the positive charges, with density proportional to charge density:

(b) Equipotential lines:

Near the heavily charged end: Equipotential lines are closely spaced and curve around this end, nearly circular close to the surface.

Along the rod: Equipotential lines are more widely spaced where charge density is lower.

Direction of increasing potential: Arrows point toward the rod (toward the positive charges). The highest potential is at the heavily charged end.

Far from the rod: Equipotential lines become approximately circular, centered on the center of charge of the distribution.

Discussion

Unlike conductors, insulators can maintain non-uniform charge distributions. The field and potential pattern reflects this non-uniformity. The electric field lines are always perpendicular to equipotential lines everywhere.

The naturally occurring charge on the ground on a fine day out in the open country is $-1.00 {\text{nC/m}}^{2}$ . (a) What is the electric field relative to ground at a height of 3.00 m? (b) Calculate the electric potential at this height. (c) Sketch electric field and equipotential lines for this scenario.

Strategy

The electric field near an infinite plane of charge is given by $E = \sigma/(2\epsilon_0)$. However, for the ground (which is a conductor with an image charge effect), the field is $E = \sigma/\epsilon_0$. The potential is found using $V = Ed$ for a uniform field.

Solution

(a) Electric field at 3.00 m height:

For a conductor (ground), the electric field just above the surface is:

The field points downward (toward the negatively charged ground).

(b) Electric potential at 3.00 m:

Taking ground as $V = 0$:

The potential is positive at height because we moved upward against the downward-pointing field (away from the negative charges).

(c) Sketch description:

Discussion

This fair-weather electric field of about 100 V/m is typical. It’s caused by charge separation in the atmosphere and is maintained by thunderstorm activity globally. A person 2 m tall standing on the ground has a potential difference of about 200 V between their head and feet! However, the tiny currents involved (the air is a very poor conductor) make this harmless.

(a) The electric field is 113 V/m, directed downward.

(b) The electric potential at 3.00 m is 339 V.

(c) The sketch shows vertical field lines pointing down and horizontal equipotential lines with potential increasing upward.

The lesser electric ray (Narcine bancroftii) maintains an incredible charge on its head and a charge equal in magnitude but opposite in sign on its tail ([Figure 10]). (a) Sketch the equipotential lines surrounding the ray. (b) Sketch the equipotentials when the ray is near a ship with a conducting surface. (c) How could this charge distribution be of use to the ray?

Strategy

The ray’s charge configuration forms an electric dipole with equal and opposite charges separated by a distance. For part (a), we sketch dipole equipotentials: concentric circles near each charge, a zero-potential surface between them, and elongated ovals far away. For part (b), conducting surfaces are equipotentials that distort nearby field patterns through induced charges. For part (c), we consider biological uses of electric fields: stunning prey, defense, electrolocation, and communication.

Solution

(a) Equipotential lines surrounding the ray:

The ray acts like an electric dipole with positive charge on its head and negative charge on its tail.

(b) Equipotentials near a conducting ship:

When the ray approaches a conducting surface:

(c) How the charge distribution is useful:

The electric ray uses this charge distribution for several purposes:

Stunning prey: The voltage between head and tail can reach 30-50 volts. When the ray contacts prey, current flows through the prey, stunning or killing it.

Defense: The electric shock can deter predators.

Navigation/sensing: Some electric fish use their electric field to sense their environment (electrolocation), detecting distortions in the field caused by nearby objects.

Communication: Electric signals may be used for communication with other electric rays.

Discussion

Electric rays and other electric fish have specialized electric organs made of modified muscle cells (electrocytes) stacked in series to produce voltage. The biological capacitor-like arrangement allows them to store charge and discharge it rapidly when needed.