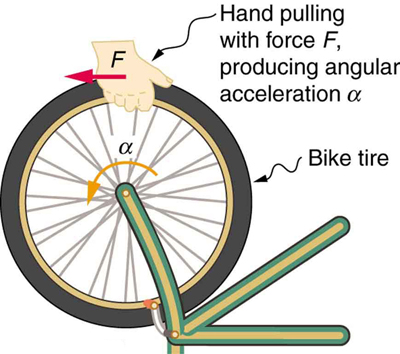

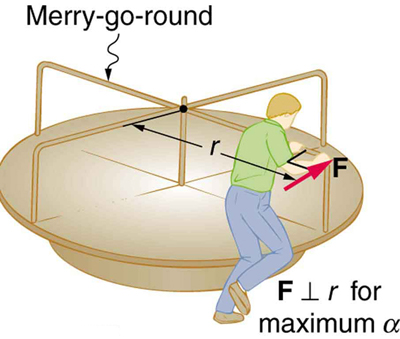

If you have ever spun a bike wheel or pushed a merry-go-round, you know that force is needed to change angular velocity as seen in Figure 1. In fact, your intuition is reliable in predicting many of the factors that are involved. For example, we know that a door opens slowly if we push too close to its hinges. Furthermore, we know that the more massive the door, the more slowly it opens. The first example implies that the farther the force is applied from the pivot, the greater the angular acceleration; another implication is that angular acceleration is inversely proportional to mass. These relationships should seem very similar to the familiar relationships among force, mass, and acceleration embodied in Newton’s second law of motion. There are, in fact, precise rotational analogs to both force and mass.

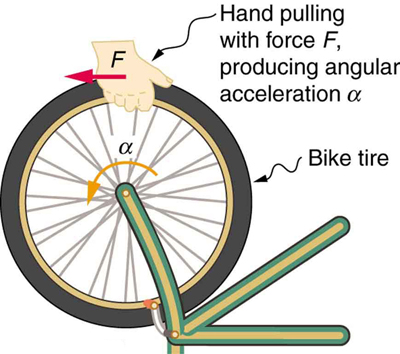

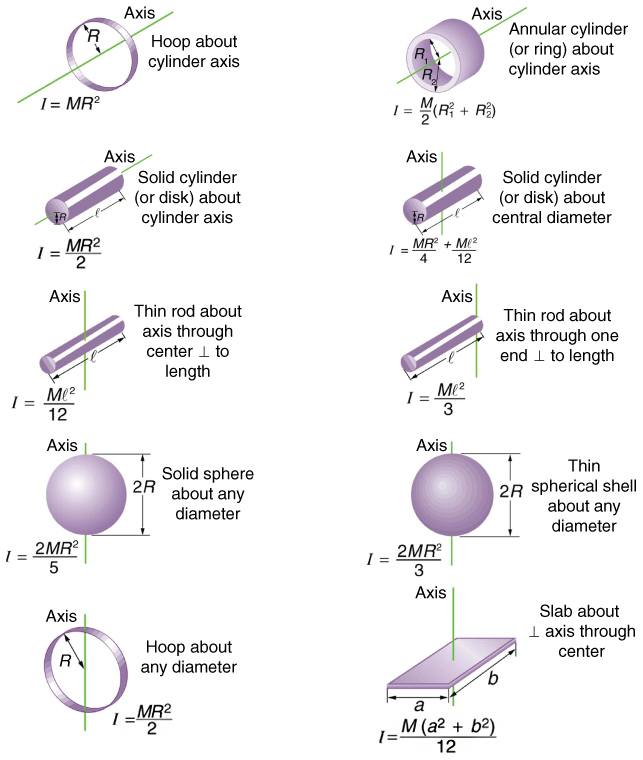

To develop the precise relationship among force, mass, radius, and angular acceleration, consider what happens if we exert a force $F$ on a point mass $m$ that is at a distance $r$ from a pivot point, as shown in Figure 2. Because the force is perpendicular to $r$, an acceleration $a=\frac{F}{m}$ is obtained in the direction of $F$. We can rearrange this equation such that $F=ma$ and then look for ways to relate this expression to expressions for rotational quantities. We note that $a=r \alpha$, and we substitute this expression into $F=ma$, yielding

Recall that torque is the turning effectiveness of a force. In this case, because $\vb{F}$ is perpendicular to $r$, torque is simply $\tau =F r$. So, if we multiply both sides of the equation above by $r$, we get torque on the left-hand side. That is,

or

This last equation is the rotational analog of Newton’s second law ( $\vb{F}=m\vb{a}$), where torque is analogous to force, angular acceleration is analogous to translational acceleration, and $m r^{2}$ is analogous to mass (or inertia). The quantity $m r^{2}$ is called the rotational inertia or moment of inertia of a point mass $m$ a distance $r$ from the center of rotation.

Dynamics for rotational motion is completely analogous to linear or translational dynamics. Dynamics is concerned with force and mass and their effects on motion. For rotational motion, we will find direct analogs to force and mass that behave just as we would expect from our earlier experiences.

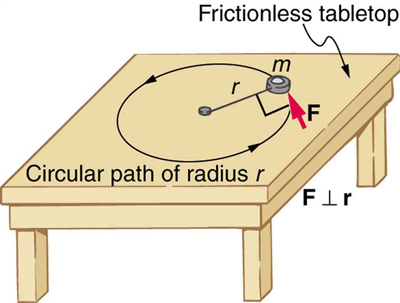

Before we can consider the rotation of anything other than a point mass like the one in Figure 2, we must extend the idea of rotational inertia to all types of objects. To expand our concept of rotational inertia, we define the moment of inertia $I$ of an object to be the sum of $m r^{2}$ for all the point masses of which it is composed. That is, $I=\sum m r^{2}$. Here $I$ is analogous to $m$ in translational motion. Because of the distance $r$, the moment of inertia for any object depends on the chosen axis. Actually, calculating $I$ is beyond the scope of this text except for one simple case—that of a hoop, which has all its mass at the same distance from its axis. A hoop’s moment of inertia around its axis is therefore $MR^{2}$, where $M$ is its total mass and $R$ its radius. (We use $M$ and $R$ for an entire object to distinguish them from $m$ and $r$ for point masses.) In all other cases, we must consult Figure 3 (note that the table is piece of artwork that has shapes as well as formulae) for formulas for $I$ that have been derived from integration over the continuous body. Note that $I$ has units of mass multiplied by distance squared ( $\kg \cdot \mm$), as we might expect from its definition.

The general relationship among torque, moment of inertia, and angular acceleration is

or

where net $\tau$ is the total torque from all forces relative to a chosen axis. For simplicity, we will only consider torques exerted by forces in the plane of the rotation. Such torques are either positive or negative and add like ordinary numbers. The relationship in $\tau =I \alpha , \alpha =\frac{ \text{net τ}}{I}$ is the rotational analog to Newton’s second law and is very generally applicable. This equation is actually valid for any torque, applied to any object, relative to any axis.

As we might expect, the larger the torque is, the larger the angular acceleration is. For example, the harder a child pushes on a merry-go-round, the faster it accelerates. Furthermore, the more massive a merry-go-round, the slower it accelerates for the same torque. The basic relationship between moment of inertia and angular acceleration is that the larger the moment of inertia, the smaller is the angular acceleration. But there is an additional twist. The moment of inertia depends not only on the mass of an object, but also on its distribution of mass relative to the axis around which it rotates. For example, it will be much easier to accelerate a merry-go-round full of children if they stand close to its axis than if they all stand at the outer edge. The mass is the same in both cases; but the moment of inertia is much larger when the children are at the edge.

Cut out a circle that has about a 10 cm radius from stiff cardboard. Near the edge of the circle, write numbers 1 to 12 like hours on a clock face. Position the circle so that it can rotate freely about a horizontal axis through its center, like a wheel. (You could loosely nail the circle to a wall.) Hold the circle stationary and with the number 12 positioned at the top, attach a lump of blue putty (sticky material used for fixing posters to walls) at the number 3. How large does the lump need to be to just rotate the circle? Describe how you can change the moment of inertia of the circle. How does this change affect the amount of blue putty needed at the number 3 to just rotate the circle? Change the circle’s moment of inertia and then try rotating the circle by using different amounts of blue putty. Repeat this process several times.

Apply $\text{net} \tau= I\alpha$, $\alpha =\frac{ \text{net τ}}{I}$, the rotational equivalent of Newton’s second law, to solve the problem. Care must be taken to use the correct moment of inertia and to consider the torque about the point of rotation.

In statics, the net torque is zero, and there is no angular acceleration. In rotational motion, net torque is the cause of angular acceleration, exactly as in Newton’s second law of motion for rotation.

Consider the father pushing a playground merry-go-round in Figure 4. He exerts a force of 250 N at the edge of the 50.0-kg merry-go-round, which has a 1.50 m radius. Calculate the angular acceleration produced (a) when no one is on the merry-go-round and (b) when an 18.0-kg child sits 1.25 m away from the center. Consider the merry-go-round itself to be a uniform disk with negligible retarding friction.

Strategy

Angular acceleration is given directly by the expression $\alpha =\frac{ \text{net τ}}{I}$:

To solve for $\alpha$, we must first calculate the torque $\tau$ (which is the same in both cases) and moment of inertia $I$ (which is greater in the second case). To find the torque, we note that the applied force is perpendicular to the radius and friction is negligible, so that

Solution for (a)

The moment of inertia of a solid disk about this axis is given in Figure 3 to be

where $M=50.0 \kg$ and $R=1.50 \m$, so that

Now, after we substitute the known values, we find the angular acceleration to be

Solution for (b)

We expect the angular acceleration for the system to be less in this part, because the moment of inertia is greater when the child is on the merry-go-round. To find the total moment of inertia $I$, we first find the child’s moment of inertia $I\_{\text{c}}$ by considering the child to be equivalent to a point mass at a distance of 1.25 m from the axis. Then,

The total moment of inertia is the sum of moments of inertia of the merry-go-round and the child (about the same axis). To justify this sum to yourself, examine the definition of $I$:

Substituting known values into the equation for $\alpha$ gives

Discussion

The angular acceleration is less when the child is on the merry-go-round than when the merry-go-round is empty, as expected. The angular accelerations found are quite large, partly due to the fact that friction was considered to be negligible. If, for example, the father kept pushing perpendicularly for 2.00 s, he would give the merry-go-round an angular velocity of 13.3 rad/s when it is empty but only 8.89 rad/s when the child is on it. In terms of revolutions per second, these angular velocities are 2.12 rev/s and 1.41 rev/s, respectively. The father would end up running at about 50 km/h in the first case. Summer Olympics, here he comes! Confirmation of these numbers is left as an exercise for the reader.

Torque is the analog of force and moment of inertia is the analog of mass. Force and mass are physical quantities that depend on only one factor. For example, mass is related solely to the numbers of atoms of various types in an object. Are torque and moment of inertia similarly simple?

No. Torque depends on three factors: force magnitude, force direction, and point of application. Moment of inertia depends on both mass and its distribution relative to the axis of rotation. So, while the analogies are precise, these rotational quantities depend on more factors.

and then look for ways to relate this expression to expressions for rotational quantities. We note that $a = r\alpha$, and we substitute this expression into $F=ma$, yielding

or

or

The moment of inertia of a long rod spun around an axis through one end perpendicular to its length is $ML^{2}/3$. Why is this moment of inertia greater than it would be if you spun a point mass $M$ at the location of the center of mass of the rod (at $L/2$)? (That would be $ML^{2}/4$.)

Why is the moment of inertia of a hoop that has a mass $M$ and a radius $R$ greater than the moment of inertia of a disk that has the same mass and radius? Why is the moment of inertia of a spherical shell that has a mass $M$ and a radius $R$ greater than that of a solid sphere that has the same mass and radius?

Give an example in which a small force exerts a large torque. Give another example in which a large force exerts a small torque.

While reducing the mass of a racing bike, the greatest benefit is realized from reducing the mass of the tires and wheel rims. Why does this allow a racer to achieve greater accelerations than would an identical reduction in the mass of the bicycle’s frame?

A ball slides up a frictionless ramp. It is then rolled without slipping and with the same initial velocity up another frictionless ramp (with the same slope angle). In which case does it reach a greater height, and why?

This problem considers additional aspects of example Calculating the Effect of Mass Distribution on a Merry-Go-Round. (a) How long does it take the father to give the merry-go-round an angular velocity of 1.50 rad/s? (b) How many revolutions must he go through to generate this velocity? (c) If he exerts a slowing force of 300 N at a radius of 1.35 m, how long would it take him to stop them?

Strategy

This problem builds on the merry-go-round example. We’ll use the angular acceleration found there (α = 4.44 rad/s² with the child on board) and the total moment of inertia (I = 84.38 kg·m²). We apply rotational kinematics for parts (a) and (b), and for part (c), we calculate a new torque and angular acceleration for the stopping motion.

Solution

(a) To find the time to reach ω = 1.50 rad/s starting from rest:

Using the rotational kinematic equation:

With ω₀ = 0:

(b) To find the angular displacement (in revolutions):

Converting to revolutions:

(c) For stopping with F = 300 N at r = 1.35 m:

The opposing torque is:

The angular deceleration is:

Time to stop from ω = 1.50 rad/s:

Discussion

Notice that applying a larger force (300 N vs 250 N) at a slightly smaller radius (1.35 m vs 1.50 m) produces a larger torque (405 N·m vs 375 N·m), resulting in a faster deceleration than the original acceleration. This is why the stopping time (0.313 s) is slightly less than the time needed to reach the same angular velocity (0.338 s).

Answer

(a) It takes 0.338 s to reach 1.50 rad/s.

(b) He goes through 0.0403 revolutions (about 14.5 degrees).

(c) It takes 0.313 s to stop them.

Calculate the moment of inertia of a skater given the following information. (a) The 60.0-kg skater is approximated as a cylinder that has a 0.110-m radius. (b) The skater with arms extended is approximately a cylinder that is 52.5 kg, has a 0.110-m radius, and has two 0.900-m-long arms which are 3.75 kg each and extend straight out from the cylinder like rods rotated about their ends.

Strategy

We calculate the moment of inertia using the formulas for standard shapes. For part (a), we use the formula for a solid cylinder rotating about its central axis: I = ½MR². For part (b), we add the moment of inertia of the cylinder (body) to the moments of inertia of the two arms, treating each arm as a rod rotating about one end: I = ⅓ML².

Solution

(a) For the skater approximated as a cylinder (M = 60.0 kg, R = 0.110 m):

(b) For the skater with arms extended:

First, find the moment of inertia of the body (cylinder with M = 52.5 kg, R = 0.110 m):

Next, find the moment of inertia of each arm (rod with m = 3.75 kg, L = 0.900 m, rotating about one end):

For two arms:

Total moment of inertia:

Discussion

Extending the arms increases the moment of inertia by a factor of about 6.4 (from 0.363 to 2.34 kg·m²). This dramatic increase is why figure skaters spin faster when they pull their arms in—angular momentum is conserved, so reducing I causes ω to increase proportionally.

Answer

(a) The moment of inertia as a cylinder is 0.363 kg·m².

(b) With arms extended, the moment of inertia is 2.34 kg·m².

The triceps muscle in the back of the upper arm extends the forearm. This muscle in a professional boxer exerts a force of $2.00\times 10^{3}\N$ with an effective perpendicular lever arm of 3.00 cm, producing an angular acceleration of the forearm of $120 \radss$. What is the moment of inertia of the boxer’s forearm?

Strategy

We use the rotational form of Newton’s second law, τ = Iα. The torque is produced by the muscle force acting at a perpendicular distance (lever arm) from the pivot point (elbow). We can solve for the moment of inertia I = τ/α.

Solution

First, calculate the torque produced by the triceps muscle:

Now solve for the moment of inertia using τ = Iα:

Discussion

This moment of inertia is reasonable for a human forearm. The small lever arm (3.00 cm) requires a large muscle force (2000 N) to produce significant torque, which is characteristic of the human body’s biomechanics—muscles insert close to joints for compact design, trading mechanical advantage for range of motion.

Answer

The moment of inertia of the boxer’s forearm is 0.50 kg·m².

A soccer player extends her lower leg in a kicking motion by exerting a force with the muscle above the knee in the front of her leg. She produces an angular acceleration of $30.00 \text{\rad/s}^{2}$ and her lower leg has a moment of inertia of $0.750 \kg \cdot \mm$. What is the force exerted by the muscle if its effective perpendicular lever arm is 1.90 cm?

Strategy

This problem is the reverse of the boxer problem—here we know the moment of inertia and angular acceleration, and we need to find the force. We first calculate the required torque using τ = Iα, then find the force using τ = Fr.

Solution

First, calculate the torque needed to produce the angular acceleration:

Now solve for the muscle force:

Discussion

The quadriceps muscle must exert about 1200 N (roughly 270 lbs of force) to produce this angular acceleration of the lower leg. As in the boxer example, the small lever arm (1.90 cm) means the muscle must exert a large force. This is typical of biological systems, where muscles sacrifice mechanical advantage for compact anatomy and a greater range of motion.

Answer

The muscle force is 1.18 × 10³ N (or 1180 N).

Suppose you exert a force of 180 N tangential to a 0.280-m-radius 75.0-kg grindstone (a solid disk). (a) What torque is exerted? (b) What is the angular acceleration assuming negligible opposing friction? (c) What is the angular acceleration if there is an opposing frictional force of 20.0 N exerted 1.50 cm from the axis?

Strategy

For part (a), we calculate torque directly using τ = Fr. For parts (b) and (c), we need the moment of inertia of the grindstone (a solid disk: I = ½MR²) to find the angular acceleration using α = τ/I. In part (c), friction creates an opposing torque that reduces the net torque.

Solution

(a) The torque exerted by the tangential force:

(b) First, calculate the moment of inertia of the solid disk:

The angular acceleration with no friction:

(c) The friction force creates an opposing torque:

The net torque is:

The angular acceleration with friction:

Discussion

The friction barely affects the angular acceleration because it acts very close to the axis (1.50 cm). Even though 20 N is a significant force, the small lever arm means the friction torque is only 0.300 N·m—less than 1% of the applied torque. Friction would be much more effective at slowing the grindstone if it acted at a larger radius.

Answer

(a) The torque is 50.4 N·m.

(b) With no friction, the angular acceleration is 17.1 rad/s².

(c) With friction, the angular acceleration is 17.0 rad/s².

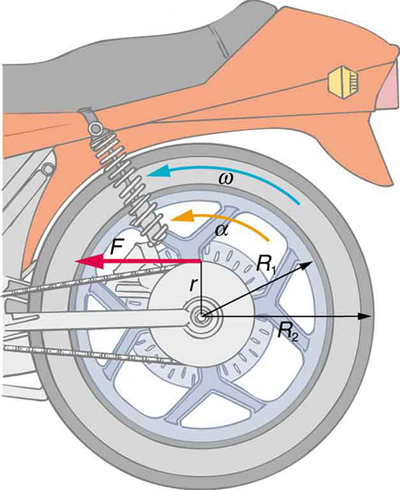

Consider the 12.0 kg motorcycle wheel shown in Figure 6. Assume it to be approximately an annular ring with an inner radius of 0.280 m and an outer radius of 0.330 m. The motorcycle is on its center stand, so that the wheel can spin freely. (a) If the drive chain exerts a force of 2200 N at a radius of 5.00 cm, what is the angular acceleration of the wheel? (b) What is the tangential acceleration of a point on the outer edge of the tire? (c) How long, starting from rest, does it take to reach an angular velocity of 80.0 rad/s?

Strategy

The motorcycle wheel is approximated as an annular ring (a ring with inner and outer radii). Its moment of inertia is I = ½M(R₁² + R₂²). We calculate the torque from the chain, find the angular acceleration, then use rotational kinematics.

Solution

(a) First, calculate the moment of inertia of the annular ring:

The torque from the chain:

The angular acceleration:

(b) The tangential acceleration at the outer edge of the tire (R₂ = 0.330 m):

(c) Time to reach ω = 80.0 rad/s from rest:

Discussion

The wheel reaches 80.0 rad/s (about 760 rpm) in less than a second, which corresponds to a linear speed of v = Rω = (0.330)(80.0) = 26.4 m/s ≈ 95 km/h at the tire’s edge. The relatively small moment of inertia allows for quick acceleration, which is important for motorcycle performance.

Answer

(a) The angular acceleration is 98.2 rad/s².

(b) The tangential acceleration at the outer edge is 32.4 m/s².

(c) It takes 0.815 s to reach 80.0 rad/s.

Zorch, an archenemy of Superman, decides to slow Earth’s rotation to once per 28.0 h by exerting an opposing force at and parallel to the equator. Superman is not immediately concerned, because he knows Zorch can only exert a force of $4.00\times 10^{7}\N$ (a little greater than a Saturn V rocket’s thrust). How long must Zorch push with this force to accomplish his goal? ( This period gives Superman time to devote to other villains.) Explicitly show how you follow the steps found in Problem-Solving Strategy for Rotational Dynamics .

Strategy

Following the Problem-Solving Strategy for Rotational Dynamics:

Solution

First, determine the initial and final angular velocities:

The required change in angular velocity:

Earth’s moment of inertia (approximating as a uniform solid sphere, M = 5.97 × 10²⁴ kg, R = 6.37 × 10⁶ m):

The torque Zorch produces at the equator:

The angular deceleration:

Time required:

Converting to years:

Discussion

Superman has plenty of time—126 billion years is about 9 times the current age of the universe! This illustrates the enormous moment of inertia of Earth. Even with a force greater than a Saturn V rocket, the tiny angular deceleration (about 10⁻²⁴ rad/s²) means Zorch’s plan is essentially impossible on any practical timescale.

Answer

Zorch would need to push for 1.26 × 10¹¹ years (126 billion years) to slow Earth’s rotation to once per 28.0 hours.

An automobile engine can produce 200 N ∙ m of torque. Calculate the angular acceleration produced if 95.0% of this torque is applied to the drive shaft, axle, and rear wheels of a car, given the following information. The car is suspended so that the wheels can turn freely. Each wheel acts like a 15.0 kg disk that has a 0.180 m radius. The walls of each tire act like a 2.00-kg annular ring that has inside radius of 0.180 m and outside radius of 0.320 m. The tread of each tire acts like a 10.0-kg hoop of radius 0.330 m. The 14.0-kg axle acts like a rod that has a 2.00-cm radius. The 30.0-kg drive shaft acts like a rod that has a 3.20-cm radius.

Strategy

We need to calculate the total moment of inertia of the rotating system (two wheels, axle, and drive shaft), then apply α = τ/I. Each component uses a different moment of inertia formula based on its shape.

Solution

First, calculate the applied torque:

Now calculate the moment of inertia for each component:

For each wheel (there are two rear wheels):

Disk (wheel center):

Tire walls (annular ring):

Tread (hoop):

Moment of inertia per wheel:

For two wheels:

For the axle (solid cylinder, 14.0 kg, R = 0.0200 m):

For the drive shaft (solid cylinder, 30.0 kg, R = 0.0320 m):

Total moment of inertia:

Angular acceleration:

Discussion

The wheels dominate the total moment of inertia—they account for over 99% of it. The axle and drive shaft contribute negligibly because their mass is concentrated near the axis of rotation (small radii). This is why performance cars use lightweight wheels: reducing wheel mass has a much greater effect on acceleration than reducing the mass of central components like the axle.

Answer

The angular acceleration is 64.4 rad/s².

Starting with the formula for the moment of inertia of a rod rotated around an axis through one end perpendicular to its length $\left(I=M\ell^{2}/3\right)$, prove that the moment of inertia of a rod rotated about an axis through its center perpendicular to its length is $I= M\ell^{2}/12$. You will find the graphics in Figure 3 useful in visualizing these rotations.

Strategy

We can use the parallel axis theorem to relate the moment of inertia about an axis through the end of the rod to the moment of inertia about an axis through the center. The parallel axis theorem states that $I = I_{\text{center}} + Md^2$, where d is the distance between the parallel axes. For a rod of length ℓ, the distance from the center to the end is ℓ/2.

Solution

Applying the parallel axis theorem to relate rotation about the end to rotation about the center:

We know that $I_{\text{end}} = \frac{1}{3}M\ell^2$, so:

Solving for $I_{\text{center}}$:

Discussion

This result makes physical sense: the moment of inertia about the center (I = Mℓ²/12) is smaller than about the end (I = Mℓ²/3) because mass is distributed closer to the rotation axis when rotating about the center. The parallel axis theorem is a powerful tool that allows us to calculate moments of inertia about different axes without performing complex integrations. This relationship between Mℓ²/3 and Mℓ²/12 appears frequently in physics problems involving rotating rods.

Answer

The moment of inertia of a rod rotated about its center is I = Mℓ²/12, as proven using the parallel axis theorem.

Unreasonable Results

A gymnast doing a forward flip lands on the mat and exerts a 500-N ∙ m torque to slow and then reverse her angular velocity. Her initial angular velocity is 10.0 rad/s, and her moment of inertia is $0.050\kg \cdot \mm$. (a) What time is required for her to exactly reverse her spin? (b) What is unreasonable about the result? (c) Which premises are unreasonable or inconsistent?

Strategy

We use the rotational form of Newton’s second law and the relationship between torque and angular momentum change: $\tau = \frac{\Delta L}{\Delta t} = I\frac{\Delta\omega}{\Delta t}$. To reverse her spin, her angular velocity must change from +10.0 rad/s to −10.0 rad/s.

Solution

(a) The change in angular velocity is:

Using $\tau = I\alpha = I\frac{\Delta\omega}{\Delta t}$:

(b) A time of 2.0 milliseconds is absurdly short. It’s impossible for a gymnast to exert a torque for such a brief period and reverse her rotation. Human reaction time alone is around 100-200 ms, and applying forces through body contact with the mat takes much longer than 2 ms.

(c) The moment of inertia of 0.050 kg·m² is unreasonably small. A typical human body has a moment of inertia of 5-20 kg·m² depending on body position. The given value is smaller by a factor of 100-400. A realistic moment of inertia would be around 5 kg·m², which would give a time of 200 ms—much more reasonable. The torque of 500 N·m, while large, is not unreasonable for a gymnast landing on a mat.

Discussion

This problem illustrates how unreasonable values for one quantity (moment of inertia) lead to impossible results (2 ms time interval). In reality, a gymnast’s moment of inertia in a tucked position is about 2-4 kg·m², and in an extended position, 10-15 kg·m². The absurdly low value given makes the calculation physically meaningless.

Answer

(a) The time required is 2.0 ms (0.002 s).

(b) This is unreasonably short—far less than human reaction time and impossible for physical contact with a mat.

(c) The moment of inertia (0.050 kg·m²) is unreasonably small—about 100 times smaller than a realistic value for a human body.

Unreasonable Results

An advertisement claims that an 800-kg car is aided by its 20.0-kg flywheel, which can accelerate the car from rest to a speed of 30.0 m/s. The flywheel is a disk with a 0.150-m radius. (a) Calculate the angular velocity the flywheel must have if 95.0% of its rotational energy is used to get the car up to speed. (b) What is unreasonable about the result? (c) Which premise is unreasonable or which premises are inconsistent?

Strategy

The car’s final kinetic energy must equal 95% of the flywheel’s initial rotational kinetic energy. We use KE = ½mv² for the car and KE_rot = ½Iω² for the flywheel (disk: I = ½MR²).

Solution

(a) The car’s kinetic energy at 30.0 m/s:

This must equal 95% of the flywheel’s rotational energy:

For a disk flywheel:

Solving for ω:

(b) This angular velocity is unreasonably high. At the edge of the disk (r = 0.150 m), the centripetal acceleration would be:

This is over 50,000 times the acceleration due to gravity. No ordinary material could withstand such forces without flying apart. Additionally, 17,500 rpm is far beyond typical flywheel speeds.

(c) The flywheel is much too small and light to store enough energy at reasonable rotation speeds. To store this much energy safely, the flywheel would need either:

A realistic flywheel for this application might be 200 kg with a 0.5 m radius, which would require only about 2,000 rpm—still high but achievable with proper materials and engineering.

Discussion

This problem demonstrates the challenges of energy storage in flywheels. While flywheels can store substantial energy, the limits of material strength constrain their design. Modern high-performance flywheels use composite materials and operate in vacuum chambers, but even these have practical limits well below what would cause 50,000g accelerations.

Answer

(a) The flywheel would need to spin at 1834 rad/s (about 17,500 rpm).

(b) This is unreasonably fast—it would produce over 50,000g acceleration that would destroy the flywheel.

(c) The flywheel is too small and light to store the required energy at achievable speeds; it would need to be much larger (0.5-1.0 m radius) and heavier (200+ kg).